The Ride of My Life (40 page)

Before the shoot, I had to hook up with the creative director and give my input about what I wanted to do. I suggested a backflip, during which I’d pretend I was pouring

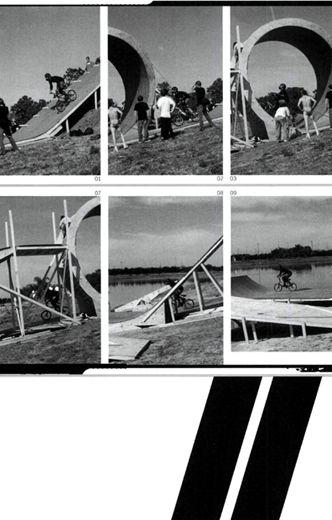

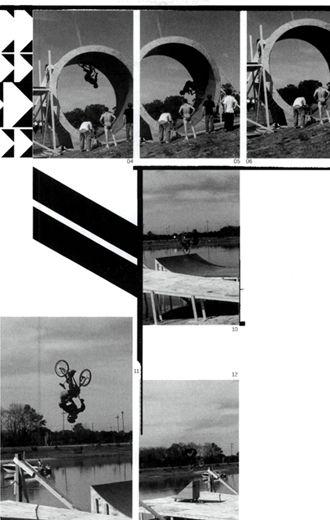

milk into the glass at the peak. I pictured a nice, big box ramp—a quick transition, a flat platform on top, and nice mellow landing ramp angling down the backside. The milk could rest on the top of the platform and as I jumped over it I’d be positioned the right way to reach for the glass—totally upside down. I wanted to hit the ramp full speed and get twelve feet of air on my arch. To get the height needed to spin a flip that big, I’d need a ramp at least six feet tall. I carefully went over the details and suggested a couple of proficient park builders to create the structure—the venerable Nate Wessel and Dave Ellis. These guys ride what they build and make sure it’s done tight, right, and certified for flight. The creative director assured me his crew had the carpentry covered. Having been part of a few commercial advertising photo shoots in the past, I mentioned it might be a super idea to let me check out a blueprint before they actually started pounding nails. A few days later a drawing arrived. It was their interpretation of what I’d described during the phone call: a two-foot-tall wedge ramp with no lip and no transition. It was like a wooden speedbump. There was a grind box down the side of the ramp, however, in case I wanted to blast that twelve-foot backflip and land it doing an icepick down the rail. Evidently these guys either really wanted me to earn my keep, or they had done their research for the ramp by playing my video game, which allows for fantasy tricks and unreal altitude. I got Dave Ellis on the phone, and he was imported to sort out the situation. A few days later I arrived on location, at an abandoned military base in Long Island, New York. There was a nice, steep five-and-a-half-foot-tall kicker with a twelve-foot deck and another twelve feet of landing ramp on the backside, waiting to greet me.

Hello, beautiful

.

Backflips are fundamentally dangerous because if something goes haywire, you’re in a very vulnerable position to land directly on your head. Pulling them at twelve feet above the ramp is not something many people do every day. But I wanted this photo to look good and wanted it done “live” instead of posing it in a studio. I started putting my gear on, and they told me it wasn’t going to work if I wore a helmet to promote the healthy benefits of good old milk. They thought I wanted to wear my helmet for looks—the reason I wear my helmet is because this shit is dangerous, and I need it. I agreed to ride without a brain bucket but pointed out the stupidity of the message we were sending—

drink milk

for strong bones, and test their strength by landing on your skull

. I told them I couldn’t do it unless there was a serious warning on the ad.

The stylist on site noted the rugged condition of my hairstyle—the result of cutting my own hair for years. In fact, I’ve only been to a real barber three times in my whole life. When I was younger, my mother cut my hair. Then I let it grow for about seven years but finally had to cut it off after I hurt my arm and couldn’t manage it any more. Since that time I’d been trimming it myself. Apparently, this feat did not impress the stylists. A professional barber was dispatched. He shook his head in dismay, and took a whack at my ’do. With clipping complete, I was ready for the final touch: my upper lip was spackled with a no-drip choco-marshmallow fluff, forming the moustache. It was windproof, wipeproof, and lickproof.

I wanted to get lit on fire in the chicken suit, go through the loop then jump into the lake to extinguish myself. MTV wouldn’t let me because some kid had lit himself on fire trying film his own Jackass stunt.

Just to clear the deck I had to crank full speed, and when I’d throw a flip it sent me flying upward twelve feet, upside down. We started shooting around ten in the morning, and by midafternoon we were still going. It had turned into a much more difficult day than I’d planned. The wind picked up and was gusting about thirty miles per hour. I had to keep guessing what the wind was going to do on my approach and laid out over fifty flips that day, all without a helmet. Every few flips, the moustache pit crew would inspect my ’stash for bugs or other inconsistencies. The wind got so bad I finally had the ramp turned around so I could approach it with the wind at my back. A gigantic, invisible hand boosted my speed, scooped me up the tranny, and sent me sailing—I cleared the entire landing ramp and just about crushed my wrists from the impact of dropping a flip to flat ground from twenty feet up.

The photographer wanted me to try a one-handed flip so they could superimpose the bottle of chocolate milk in my hand during the art direction process. Every time I tried a one-handed flip I couldn’t maintain an even pull tension on the handlebars. I did a few, and each one I flew through the air with such stink butt style, leading the trick with my ass instead of my head. I didn’t want my moment of milk ad stardom to be marred by stinky style. So we faked the one-handed part. I lay upside down atop of the platform and poured my milk into a glass. The wind actually helped, making it look more real by blowing the milk around as I poured it.

A few days after the shoot, I got to check out the photos and go over the composition and what the backdrop was going to be. From the angle it was shot, my flip looked about seventy-five percent lower than it actually was. But hey, the spilling milk looked perfect. As a lifelong chronic beverage spiller, that was nearly as important as a sky-high backflip. The art director suggested the ad layout feature me doing a flip through outer space, with the glass positioned on a nearby planet. I asked about flipping through New York City, grabbing for the glass over the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. The ad was going to debut in national print, billboard, bus shelters, and on the Internet in August 2001 and be up for a while. I am so glad they declined to use my Twin Towers suggestion. We decided on the nondescript ramp edge, and blue sky as the backdrop. When it finally came out, I can remember standing in my brother Travis’s coffee shop and picking up a copy of

USA Today

. On the back cover of the sports section there was a full page

Why Milk?

ad, sort of an end-of-the-year compilation featuring six of the top athletes in the world, including my shot and the

Why Milk?

ad starring Tony Hawk. People in the coffee shop crowded around, clapped me on the back, and congratulated me for being included among such superstars. They were so stoked for me. I felt like an idiot—I had no idea who any of the other athletes were on the page, except Tony.

I guess I just don’t watch enough TV.

I’ve always secretly wished I’d been in RAD, the first film focused on freestyle back in 1987. The opening credits of RAD were highly promising and featured straight documentation of a gaggle of pros hotdogging in the fog. That was the scene I wanted to be in. After the first two minutes of the film, the story line kicked in. The plot had so much cheese slathered on it, you didn’t even want to admit you owned a bike, much less rode one. At one point in RAD, there’s one pivotal “tender moment” in which flatland pro Martin Aparijo, in a bad wig and stunt doubling for a female character, rides a bike onto the dance floor of a nightclub. He attempts to seduce a guy (played by Olympic gymnast Bart Conner, also riding a bike indoors on the dance floor) by doing flatland freestyle. The routine is delicately lit with a rainbow of lights and choreographed to the rhythm of the 1983 synth hit “Send Me an Angel,” by Australian haircut band Real Life. It’s one of those moments that’s just so bad, your entire body cringes when you’re exposed to it—like radiation.

The effects of

RAD

were so long lasting, it would be fifteen years before another flick with bikes hit the silver screen. And then, suddenly, there was a glut of bike footage being thrust into the spotlight. It started around 1999, when a crew from Imax contacted ESPN2 about making a documentary on action sports athletes. The Imax films are projected on screens five stories tall, so the “more-is-more” philosophy applies to the coverage. When Imax film crews showed up at a contest, some riders and skaters balked, because they were concerned they wouldn’t be compensated. I got lucky and was interviewed off-site, so I got paid. But cash wasn’t my top priority—I was more concerned about how cool it would be seeing the big ramp in such a big environment, and I let them take a few clips of me from the X Games and supplemented that with some footage of the airs I did on my twenty-four-foot-tall quarterpipe.

Around the same time the Imax film was being put together, another documentary,

Keep Your Eyes Open

, began production with director Tamra Davis at the helm. It featured segments on big-wave surfing, skateboarding, freestyle MX, snowboarding, and bike stunt riding. I was pretty psyched to have a segment in

Eyes Open

, alongside guys like skaters Eric Koston and Steve Berra, MX heavyweight Travis Pastrana, and snowboarding siblings Mike and Tina Basich. From the clips I’ve checked out so far, all the people featured in it seem amazing. It’s the best film I’ve seen documenting our sports that wasn’t made by bike riders, skaters, or snowboarders. There’s also a couple of comic relief scenes with Spike and Tamra’s husband, Beastie Boy Mike D, playing hard-assed security guards.

In 2001, Rob Cohen, a veteran director responsible for a fistful of action movies (including

Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, episodes of Miami Vice

, and the breakout hit chronicling midnight drag racing culture,

The Fast and the Furious

) began preproduction on another film grounded in action sports. Rob got together with Samuel L. Jackson, and the star of

Fast/Furious,

Vin Diesel, to create

XXX

. Vin plays an action sports adrenaline junkie named Xavier, and he’s eventually recruited by an elite intelligence

agency to become a modern-day James Bond. I got hired for a few days as a technical adviser, to help Rob and Vin understand some of the nuances of the hardcore action sports lifestyle. The production was heavy on stunts, ranging from B.A.S.E jumps out of cars plummeting off bridges to insane motorcycle leaps. Vin and Rob and the crew were pretty nice and totally in their element in the hectic atmosphere of a Hollywood production. For me, it definitely felt strange telling a guy who was getting paid ten million dollars how to act like he was into the same stuff my friends and I have been doing all our lives (and earning a fraction of a fraction of that salary), Rob and I had a good vibe from one another, and he asked me if I’d make a cameo in the film. I told him yes and got a copy of the script to study up for the shoot day.

I played “Extreme Guy Number #1” and was required to eloquently exchange a line of dialogue with Xavier in the midst of a surprise party. Just moments later, the party would be raided by jack-booted commandos in ski masks, and Xavier was drugged and kidnapped. My line was something to the effect of, “Yo, that last stunt was sick, dude. Can I join you next time?” I was flown to California for an all-night shoot and on the set hooked up with a few friends who were also there to play bit parts as extras and make the scene in general. Rick Thorne was there, and so was Rooftop, Tony Hawk, and a couple other skaters. We were all part of the action sports party posse. Our job was to stand around and look extreme. During the night, Rob approached me and told me how psyched he was that I’d made it and said he’d dedicated the automobile B.A.S.E. jump in the film to me.

The set was still buzzing from a near-tragedy the day before. Larry Linkogle of the Metal Mulisha MX contingent had been doing a big air jump for a scene, leaping his Yamaha across an eighty-five-foot gap. A camera crew had gone up in a helicopter to get the shot. During one of the jumps, the chopper pilot brought his bird in too close, and a spinning rotor blade struck Larry’s helmet. The force ripped Larry off his bike in the air and sent him pile-driving into the dirt. Another fraction of an inch and the blade would have lopped off his head. Larry blew everybody’s mind when he got up and walked away from the crash. The intensity of the occupational hazards of action sports athletes had not escaped the Hollywood folks.