The Ride of My Life (37 page)

The sports media, especially the mainstream, didn’t understand it at all when I said I was retiring from contests so I could have more time to ride. They couldn’t figure out how I could be retired and still participate in the sport as a professional. They wanted to know how I could contribute if I didn’t compete. I told the confused journalists the only contender you need in our sport is your personal limits, and I had a few projects up my sleeve to challenge those limits.

My biggest prize in life is at home, waiting for me every day when I walk in the door. On December 19, 2000, Jaci and I had a baby, Giavanna Katherine Hoffman. Baby G was amazing, inspiring, and pure energy. Being new parents threw our schedules into chaos; five o’clock in the morning wakeup calls, feeding, playing, and the comforting needed to make a baby feel safe and loved. Gianna was definitely into lung power her first year, crying a lot. She progressed into crawling and quickly dominated our house, drooling on all the electronics and terrorizing the pets. I never thought I could top the feeling of riding vert. Now I have a tidy little package with a smile on her face and eyes that light up every time she sees me, and I truly know how good I have it. People would say, “When you have a baby, you’ll mellow out.” But Gianna inspired me to celebrate who I am even more. She added a love to my life that I didn’t know was possible, and this came out when I got on my bike. With her as my fuel I didn’t need to focus my goals around competition. She is my inspiration to ride and keep progressing.

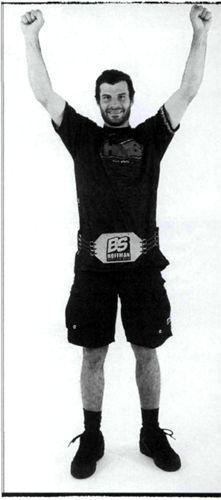

When a rider wins the BS Champion belt, the rules stipulate they have to wear the belt all night long, to whatever festivities take place. It makes for a comical evening at the finals.

I’ve experienced the intensity of driving myself—and a sport—for almost twenty years. Now I’ve got this beautiful little girl, who doesn’t give a damn what I can do on a bike. I’m not a world champion, or a crazy freakin’ biker. I’m just… Dad.

That’s the only gold I need.

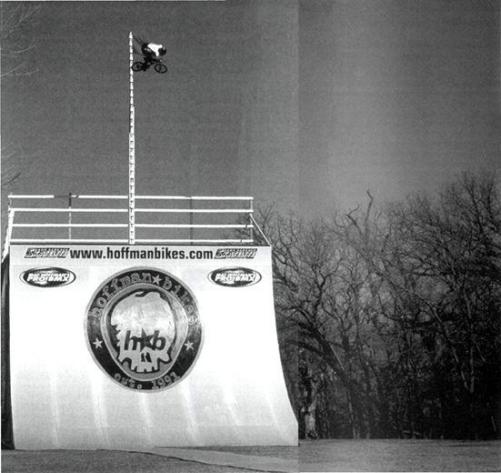

This is the air that got me thinking I could double the height of this fifteen-foot air and clear thirty feet if I doubled the height of the ramp. (Photograph courtesy of Mark Losey)

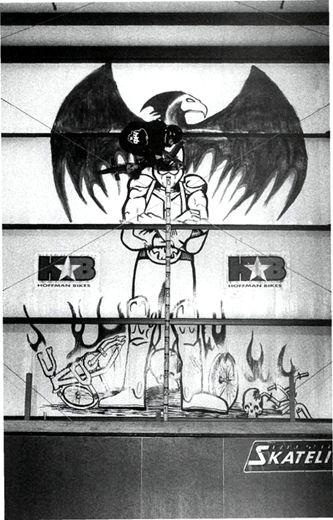

SETTING THE RECORD STRAIGHT

Ramps are not dangerous unto themselves. Confidence. Now that can be dangerous.

In 1994, I pulled a twenty-three-foot aerial out of a twenty-one-foot-tall quarterpipe. It was the highest air ever done on a bicycle, and one of the most fantastic feelings I’d ever experienced riding vert. But I have an addictive personality. Even as I cleared my own world record, I knew it was possible to top thirty feet, given the right ramp and the proper speed. Injuries kept me from my elusive dream for seven years.

In 2001, I had the indoor park adjacent to the Hoffman Bikes warehouse updated with some new terrain. The featured attraction was a halfpipe with eleven-foot-tall transitions, capped with nearly two feet of vert. I could roll in from a platform twelve feet above the deck (twenty-five feet off the ground] and B-O-O-M, a fifteen-foot aerial on the first wall without breaking a sweat. It was the perfect place to play, and of course, I got injured very quickly. I knocked myself out pretty good on one occasion

and wasted my knee on another. It took knee surgery and a new approach to my life before I was consistently floating fifteen-foot airs again. And that was when I steered down the path of no return: the desire for impossibly big airs was reignited. The more I thought about it, and what a cool stamp it would be on my career …

thirty feet!

… the more I wanted it.

When I lock into an idea that stokes me, I enter a state of mind I can only describe as

consumed

—I’m basically along for the ride and at the mercy of whatever project is on the table. That drive, combined with a love for looking down past my right shoulder and seeing the coping way below me, is what led me back into big transition territory.

So close to clearing the pole, but not quite…

The first obstacle I faced was my family and friends. I’d always been blessed to have an inner circle of people who believed in me through good times and bad, who contributed to my success in a million different ways. Everybody should be as lucky as I am to be surrounded by such great people. But I started bringing up the term giant ramp and ran into a wall of resistance from everybody on this one. Jaci didn’t want me to do it. Steve didn’t want me to do it. Nobody wanted me even thinking about riding another big ramp. I’d always justified the unacceptable aspects of my lifestyle by calling my conviction an addiction:

“I can’t help it—this is the way I am

, it’s who I am, and what I have to do.”

So, despite their best efforts to dissuade me, my family and friends gave in. I was beyond help.

I knew exactly what they were afraid of—the same thing I was. I’d lost a spleen on previous high-air attempts. The force of impact from a fifty-foot crash could leave me broken beyond repair, or worse. But rather than be intimidated by the odds, I let the possible consequences dictate just how seriously I needed to approach my goal. I didn’t want any excuses, and if I did get, as the saying goes, majorly fucked, I never wanted to look back and say, “I should have built a better ramp.”

I called Tim Payne, a vertical engineer of serious reputation, and laid out the plan. Tim and his crew of Dave Ellis and Mike Cruz—Team Pain—arrived in Oklahoma City within a couple weeks. They brought the power tools of the trade and a sizable shopping list of materials. No more screwing around, nursing the project along for weeks and months, or standing on scaffolding in the middle of an ice storm trying to finish. I wanted this ramp to be flawless. Perfection came with $30,000 tag. The crew tore into the job like piranha, and my ramp went up in four days. When it was done, the structure stood twenty-four feet tall—twenty-two feet of transition with two feet of vert. Tim shook his head, shook my hand, and wished me luck. I cut him a check, and he was gone.

The final factor in the formula was momentum. I needed speed to get high: forty-five to fifty miles an hour at least. Early experiences with Steve’s YZ 125 revealed his cycle wasn’t cutting it. To get rolling that fast meant a motorcycle purchase, a bigger bike with a 250 engine, with the get-up-and-go to tow my 165-pound body and 35-pound bike. Forty-five hundred dollars later, we had a Yamaha YZ dirt bike. Steve, my tow pilot, needed convincing that I would not kill myself. I bartered with him, promising that if he towed me, just this one last time, I’d start wearing the seat belt in my car (a dangerous habit not to, I know… but… I just never could do it). Steve was aware that if he refused, I’d just get Page or one of the other guys to tow me. I was radiating confidence that I could pull it off, and so Steve reluctantly agreed.

The ramp was stationed on some unused acreage on my dad’s property. There was a four-hundred-foot long plywood runway leading up the face. We made giant Mat Hoffman Pro BMX stickers, stuck them at the edges of the ramp, and painted a huge Hoffman Bikes skull logo in the center. At the peak of my airs, I had to aim for the paint, which lined me up about eight inches away from the coping. That comfort zone gave me plenty of transition to land on but also ensured I didn’t hang up if the wind pushed me back toward the deck. Landing too low or hanging up from a height of twenty-something feet over coping would have catastrophic results.

Here she is. Tall, intimidating, unforgiving, and the thrill of a lifetime.

There was a mix of tension, concentration, and glee as I started warming up. The ramp was solid as a mountain, and the runway was reasonably smooth, with the exception of a small bump where water drainage had formed a contour in the ground. I had my approach timing worked around the topography and knew when to ready my body by the way the earth felt as it sped by underneath my wheels. When I passed a certain tree I’d throw the knotted nylon towrope, being careful not to run it over. Then I’d hit the tranny and go straight up. Instead of airs, it felt like I was doing kickturns or fufanus in the sky. There was very little arc, just an incredible rush of momentum shooting me off the coping, and a few seconds later I reached my peak and gravity stalled out. Then I had to figure out how to turn around and get down from almost five stories up.

I felt it right away. The first day I was hitting the twenty-five- to twenty-seven-foot range, higher than I’d ever gone before. There were a couple of airs that were absolutely beautiful—the perfect merger of flesh, steel, air, and wood. Despite the smooth form, I was just a couple feet short of the height I wanted. I could taste victory. I knew it was only a matter of time before I solved the puzzle of the perfect pump up the transition, and a thirty-foot air would be mine. There were a few kinks to work out, like the speedometer on the motorcycle. It was registering a steady fifty miles per hour on approach, but sometimes it felt as slow as forty-eight, and on other runs it might have been up around sixty. It was one of those things I had to adjust to on the fly, using only my instincts.

The confidence I felt was blinding me to the dangers at hand, however. Riding big ramps required me to convert all my natural sense of caution into a sort of hyperawareness. I was so focused on what I had to do that I ignored the warning signs: a couple of sketchy landings where my arms almost gave out, another where I slid out on the way down the tranny and was sent skipping across the ground, leaving divots in the turf I bounced to my feet and threw both arms up—to signal that I was okay—but it was close. I could feel everybody around me tighten up. There was another air when I missed my timing so badly that I just shot straight up, stalled, and began falling in sideways. I dropped a good six feet drifting in that position before I was able to coax my front end and point it into the ramp, using body English to finesse myself around. Old school riders may remember a ramp trick called the Jammin’ Salmon—you used your bike like a fin and “swam” through the air. That’s what I had to do to save that one. I played it back on the video camera and the height was almost there, though. Another couple feet and I’d top the pole. I could feel the thirty-footer in me, just waiting for everything to click …