The Ride of My Life (31 page)

When I got to the bottom I told John I couldn’t believe how scary that one had been. “Yeah, I’d never try that shit,” said John, referring to my double gainer. It freaked me out a little to hear that, because there was one more thing I wanted to try on my last jump, and it would be gnarly.

The next morning I spooned oatmeal into my mouth and swallowed. Sometimes I’m afraid of myself. But fear can be good. It’s the way my mind demands attention and concentration. A half an hour later we started our hike. My thoughts racing with each step, from what I’d need to do to survive the day, to “

What am I doing here

?” I had many friends tell me this was crazy. I hadn’t even furnished Jaci with the full details—she didn’t want to know. I knew the consequences if I failed, but I was at a crossroads in my life; I’d lost my mother, my body wasn’t allowing me to thrive on my bike, and I wasn’t interested in retiring to be a businessman, so where could I go? What was my purpose? I let spontaneity guide me, searching for an answer that changes every time I find it. Today was my day to live or die, to challenge my abilities against fate. Today was my day to ride a bicycle off a thirty-two-hundred-foot cliff in Norway and do a double backflip.

At the top of Kjerag it seemed especially pretty. Everything was in place, my head was clear and nerves were steeled as I prepared to toss my spirit off the mountain and into the air. Just as I had my thoughts collected and was ready to get it on, I realized the handlebars on my bike were totally loose. I patted my pocket for the Allen wrench and realized it was back at base camp. At first I was so pissed, but I tried to shut down my emotions so I wouldn’t lose focus. “I’ll get it,” John volunteered and vanished over the

rim. It happened so fast; it was funny. I had a few more hours to contemplate fate and take in the tranquility. I sat there next to my bike on top of the world, overwhelmed with awareness. Sometimes you’ve got to lose your direction to find your place, and I felt I had found it at that moment. I was at peace with myself, my past, and whatever was in my future. I took a nap on the edge of the cliff and waited for John. I had a dream I fell out of bed, and it woke me up.

The energy was in the air and it was time. My gear was perfect, the bike ready, and my head in tune with the task at hand. John uttered a brief B.A.S.E. jumper’s prayer. Suddenly the radio came alive with a message that we’d have to wait a few minutes before we could jump; a mountain rescue team needed to make their weekly helicopter flight through the canyons just off Kjerag. We heard the approach of rotor blades echoing off the rocks and then saw the choppers. Talk about a heavy demonstration. Rather than freak me out, though, it just hardened my resolve.

The edge sloped down at a thirty-degree angle. I rolled down the rocks, and shot off the edge like a bottle rocket. I had speed to spare, but overcoming my momentum and nailing two consecutive backflips was going to be tricky. I had six seconds to play with, and six more seconds to track away from the ledge. I held the grips white-knuckle tight as I rotated through my first flip, feeling the rushing wind trying to steal my bike. I started my second rotation and maintained a hard arch to help coax it around. Never before had I felt so

in

the moment and experienced such a pure state of mind, body, and being. I was on superautopilot, not thinking about what I was doing but doing it exactly right.

I had gone over every detail of the jump mentally, had a counter-measure for every possible crisis. Except my stupid pant leg getting caught in the chain. I was flipped upside down, bombing toward earth at one hundred and fifty miles an hour with a bike stuck to me. I kicked both legs. Hard. The thirty-five-pound bicycle broke free and continued its journey. I threw my arms back to track and straightened my legs, but was too stiff. I waffled out of control and forced myself to relax, let the wind flow with my body and carry me into a lateral track away from the shelf that was rapidly approaching.

I popped my chute and it opened with a violent jerk and in an instant it twisted around one hundred eighty degrees, sending me face first toward the cliff. Swooping toward the rock wall, I grabbed my risers on instinct, using both arms to pull with all my might to the right. If I’d followed skydiving protocol and grabbed the toggles and tried to steer, it would’ve been too late. My canopy snapped around toward the fjord and away from doom.

Suddenly I was on the ground, overwhelmed with emotion and just pure existence. I had never felt more alive. My heart was roaring. My soul was quaking with the power of what I had just done, something that was not supposed to be physically possible. At least, not without a parachute and a dream. I felt like I was living on extra credit, or I’d just earned an extra life.

I have always been jealous of people who can sit on the porch and watch a sunset and be content. No matter how hard I try, I can’t be like that. To me, life-threatening situations seem like life at its best. Our small expedition left Norway the next day. I went to England for the Backyard Jam, then from there onto the World Championships in Holland. I spent the remainder of 1997 organizing and executing the first bike/skate tour in Malaysia. I put the parachutes in the closet all winter, waiting. Before the cliff jump, I promised myself if I lived through it I was going to close this chapter of my life and start a new one. But I just couldn’t stop thinking of how to top it with something more intense. My rational side told me if I couldn’t shake the feeling, I might not be around too long. I had developed a heightened tolerance for risk and continuously needed to make things even more dangerous to satisfy my spirit.

June 1998. Tony Hawk and I were doing a show for Charles and Jill Schultz in an ice arena in Santa Rosa, California. There was a box jump, and I decided to do a superman. My cranks flipped, I missed the pedal, and landed straight-legged on my right leg. Since my knee was weak, it buckled backward, and the leg completely folded with my foot coming up to meet the kneecap. My ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) and PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), which work together to keep the knee stable and the meniscus in place, were instantly blown out. As I continued to crash, my foot got caught between my rear peg and the ground, and my leg whipped around the other way and snapped back in the socket. It felt gross to see my leg bend backward. It was just… wrong. I cried, not from physical pain but because I thought my riding days were over. For one year, I lost my knee and couldn’t do anything with my leg, not even skydive. I was unable to pursue my passion and lacked any action. I was going crazy. During my downtime, I stepped back and examined my life and what kind of risks I was putting myself through.

I think this injury probably saved my life.

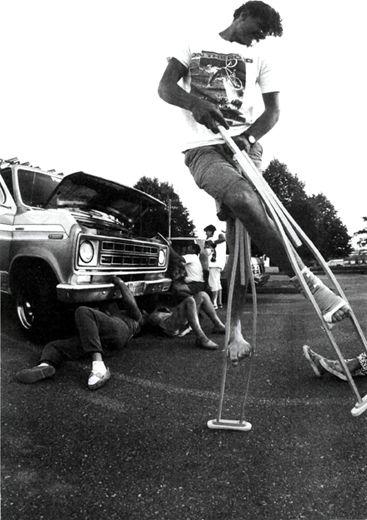

I broke my ankle in the middle of the 1987 Skyway tour, and the van was vapor locked in a parking lot. So I had to entertain myself. Unfortunately, this photo illustrates how much time I’ve spent on crutches. (Photograph courtesy of Steve Giberson)

THE SOUND OF THE BONE DRILL

I’ve broken one wrist five times. The other wrist, three times. Between my ankles, I’ve had five breaks. I’ve snapped four fingers, my thumbs four times, my hand twice, busted my feet three times, and broken three toes. (You don’t think a broken toe would hurt that much, but your entire body weight is on it.) I’ve busted my collarbones five times; snapped my pelvis, my fibula, and my elbow; and cracked three ribs and separated a couple from my sternum. (Breaking ribs off the sternum sucks—just about every movement you can think of is centered in your chest.] Then there’s my head: one skull fracture, two broken jaws, two broken noses, a mouthful of teeth, and a partridge in a pear tree.

Every choice you make can be traced back to the instinctual need to seek pleasure, and avoid pain. These two forces are interconnected, different sides to the same coin. Since I started bike riding, I wanted more than anything to experience the highest highs. To get there, I was willing to accept the consequences. My medical records contain more than four hundred pages documenting my injuries. I’ve put myself in a coma, had over fifty knockouts and concussions, been sewn up with over two hundred stitches, dislocated my shoulder more than twenty times, broken about fifty bones, and had fourteen surgeries. I’ve torn ligaments, bruised tissue, severed arteries, spilled blood, and left hunks of my skin stuck to plywood, concrete, dirt, and bicycle components. I’ve had to endure not just physical pain, but the mental anguish of relearning how to walk, ride my bike, or even remember who I was. I’ve dealt with mountains of health insurance red tape and condescending doctors who took it upon themselves to lecture me before they treated my injuries, as if they needed to save me from myself.

Not everyone understands that I’ve asked for it, accepted it, and willingly volunteered. Not to sound sadistic, but I consider each of my injuries a tax I had to pay for learning what I could do on my bike. I wanted it all and wouldn’t take any of it back if I could. Yes, I will be sore and broken when I’m older. I can feel it already, the aches and pains of a body that has been beyond and back. I’ve given up as much of myself as I could, because I love bike riding that much.

My insurance companies have always hated me, having paid hospital bills totaling more than a million dollars over the years. I’ve had to rely on surgery more than a dozen times to keep me going. You know it’s getting serious when you start letting people take knives to your body to make you healthy.

Here are my patient notes.

November 1986. It was immediately following a Mountain Dew Trick Team show. I’d just learned 360 drop-ins and was uncorking them all day. We finished our demo, but I still wanted to ride. I took my chest protector off, figuring I’d just do easy stuff. I lined up parallel to the coping to do a simple hop drop-in, like Eddie Fiola used to do. I stalled in position for a second and went for it. For some reason my brain told my body to react as if I was doing a 360 drop-in. I fell straight to the cement and took the hit on my head and shoulder. My friend Page said it made a sound like a helmet being thrown off the ramp with nothing in it—a loud, hollow snap. That was my grand finale. I didn’t just break my collarbone, I shattered it. I knocked myself unconscious, too. The show was right next door to a hospital, of all places, with two of the best surgeons in Oklahoma City on duty that day. In surgical terms, Dr. Grana and Dr. Yates performed a fourth-degree AC joint separation procedure, provided reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligament, and did a partial removal of my left collarbone.

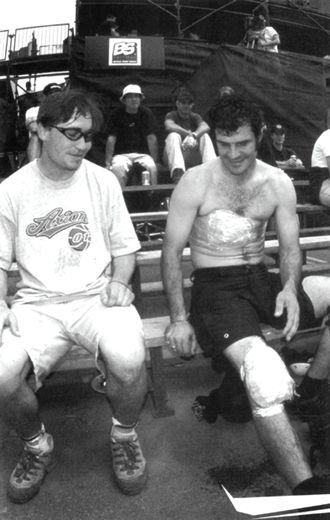

I hate ice! … but sometimes it works. (Photograph courtesy of Mark Losey)

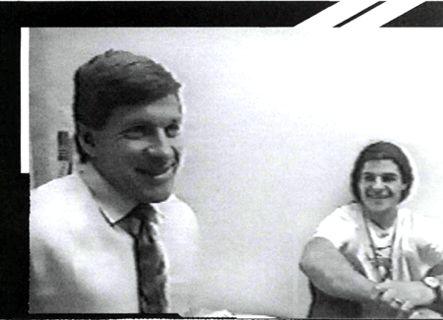

This man is the reason I didn’t have to retire at age fifteen. Thanks, Dr. Yates.

February 1988. The 540 is a trick that makes you earn it to learn it. The price is a lot of slams. I finally thought I had them just about dialed in and did one and looped out. My leg got caught behind me and I sat on it. There was a snapping sound and a blast wave of heat, pain, and nausea. Broken bones have a dull, throbby kind of ache to them. I got into Steve’s car to go to the hospital. Every time he hit a bump my leg would sway between my knee and ankle. My body was in shock, and the pain began to subside. We started chuckling every time it swayed, and then started laughing harder about what the hell we were laughing at. Dark humor helps. The doctor I encountered in the ER had very little humor. My first question to him was, “How long before I can ride again?” He told me I would be lucky to walk without a limp and would never ride a bike again. “Okay, thanks… bye,” was the next thing out of my mouth. I left that doctor as fast as I could, and my dad got me in to see Dr. Yates. Yates put in a titanium plate (the body rejects steel) and ten screws in my fibula to repair my right leg. I missed the first King of Vert in Paris because of this injury.