Where Did It All Go Right? (47 page)

Read Where Did It All Go Right? Online

Authors: Andrew Collins

Denholm Elliot went from the Hotel du Lac to the Bangkok Hilton. We went from Mr and Mrs Williams’s farmhouse to a Jersey hotel named after a borough in South London.

It may seem perverse to say it, but my Seventies ended in 1980. I think they must have started in 1970 too. Oh well. You can’t force these things.

* * *

You’ll remember that Mum dressed Simon and me as twins when we were growing up. It didn’t work. You can’t force these things. They encouraged me to take English A-level so that I could always become a journalist. That worked. They brought me up to look after my things and be nice to those around me and come home for my tea. That also worked.

Mum tried to indoctrinate me with mispronunciation of foodstuffs but I chose my own path. Dad tried to indoctrinate me with

Thatcherite

self-interest – for my own good, of course – but I failed him there, just as I had done by taking no interest in cricket. At the end of the day, my parents did very little moulding, allowing all three of us to follow our instincts – Simon into khaki, me also into khaki but as an art fashion statement, and Melissa into the bank. I’ll bet they wouldn’t do anything differently if they had the chance to go back and do it again – except perhaps

Ilfracombe.

1.

Having resisted Mum’s attempts to turn Simon and I into twins all my life, I saw no irony in the fact that Kevin and I wore exactly the same clothes and had exactly the same hair when we went into town.

2.

Minor industrial noise band, most famous for ‘Metal Dance’ and not being Einsturzende Neubaten.

3.

Also Harmony, Country Born, Bristows and Sunsilk.

4.

‘For being there.’

5.

The band that rose from the ashes of Bauhaus and enjoyed moderate success in America. This line is from ‘Dog-End of a Day Gone By’ a song on their first album, 1985’s

Seventh Dream of Teenage Heaven

.

acknowledgements

Everyday People

It’s not practical to thank all those who have written miserable memoirs about their terrible childhoods, but collectively they inspired me to write this book with their redemptive and more importantly best-selling tales of woe: abuse, death, deprivation and the search for love among the wreckage. The aim of

Where Did It All Go Right?

is not to belittle their suffering, or to mock the therapeutic qualities of externalisation, but simply to provide an alternative view.

Shit happens. But sometimes it doesn’t.

The degradation endured by the young Dave Peltzer (

A Boy Called ‘It’

and numerous sequels) may in fact be the polar opposite of my childhood, but I started to think in mid-2000 that, hey, perhaps my voice should be heard too. Then I read Paul Morley’s elegant book

Nothing

and my mind was made up. Perhaps then I should single out Paul Morley for sincere appreciation above all the other whingers.

It almost seems indulgent to thank my family when the book is dedicated to them, but clearly I could not have told my story without their blessing, as it is their story too. While writing and researching it, I spent valuable quality time with them, sorting through boxes of memorabilia in Mum and Dad’s loft and sorting through events in our minds. Of all my grandparents, it was only Pap Reg who looked likely to see the book’s publication but sadly he died while I was writing it. That’s a mortal watershed for any grandchild, and it was for me, but it made the book seem more

important

to finish. I hope I have done a halfway decent job. I like to think that my late father-in-law, Sam Quirke, would have enjoyed it too.

I read two very different autobiographies during the writing of this one that fed directly into it:

Experience

by Martin Amis and

Frank Skinner

by Frank Skinner. One gave me the conviction to run footnotes on the page, the other made me feel a lot better about the occasional coy reference to a teenage girlfriend (if you’ve read it you’ll know exactly what I mean). I also found inspiration in the first published diary (1660) by Samuel Pepys – the guv’nor! – and in Gavin Lambert’s memoir

Mainly About Lindsay Anderson

, in which he quotes from the great British director’s first diary (1942), aged 19. ‘Its purpose is both to remind me in after years how I felt and what I did, [and] to give me literary exercise.’

Two people were instrumental in helping me treat a labour of love as a literary exercise: firstly my great friend and agent Kate Haldane, who read the sample chapters and laughed (I can’t believe it – I’ve just thanked my agent!), and secondly the man who turned out to be my publisher, editor and pal, Andrew Goodfellow at Ebury. He phoned Kate seemingly out of the blue and asked if certain of her clients were interested in writing a book. I was; she quickly arranged the lunch at a restaurant that stupidly serves wine but not beer, and thanks to Andrew’s long-sighted vision – and his Seventies childhood – a deal was struck.

Only one person read the book before these two did (apart from my mum), and that is Julie Quirke, who wisely kept her own name when she married me. I have taken her advice on style and ethics throughout, and do nothing without seeking her approval, except buy John Wayne DVDs.

Life would have been a lonely writer’s hell were it not for the good people who continue to populate the rest of my life: Adam Smith, Frank Wilson, Gary Bales, Jax Coombes, Julie Cullen, Mark Sutherland, Stuart Maconie, Simon Day, Alex Walsh-Taylor, David Quantick, John Aizlewood, Rob Mills and Jessie Nicholas, Lorna and Peter, John and Ginny, Howard and Louise, Eileen Quirke, Mary and Steve Rowling, the combined Quirkes, Collinses, McFaddens and Joneses; all at Amanda Howard Associates; all at

the

mighty 6 Music, not least Jim, Adam, Mark, Miles, Gid, The Hawk, Mr Tom, Tracey, Jupitus, Wilding, Claire, Gary, Jo, Mike, Mike, Webbird, Joti, Lauren, Sarah, Jon, John, Antony and everyone else who knows me; all at BBC Radio Arts including Stephen, Sarah, Paul, Toby, Mo, Zahid, Elizabeth, Mark, Francine and all the Johns; Gill, Sue, Colin, Shem, Flynn, Ruth, Philip and all at

Radio Times

; Sarah, Rachel, Hannah, Jo, Di, Jake and all at Ebury; Jim and Lesley for altering the course of my life; and, while we’re in the corridors of power, John Yorke and Mal Young, without whom …

Name-dropping: thanks to Richard Coles for geographical support, Billy Bragg, Juliet and family for continued inspiration, and to Mark Radcliffe and Marc Riley for laughing out loud at my diaries on late-nite Radio 1: you are honorary ‘dirt collectors’.

Respect to those writing peers who said nice things: Mil Millington, Augusten Burroughs, Rhona Cameron, Richard Herring and Danny Wallace.

Hats off to Friends Reunited, the website that reached its tipping point at just the right time for a book about old schoolfriends, and to all those who got in touch: Paul Milner, Paul Bush, Anita Barker, Catherine Williams, Alan Martin, Dave Griffiths, Craig McKenna, Jo Gosling, Jackie Needham, Kevin Pearce, Wendy Turner, Sue Stratton, Lis Ribbans, Louisa Dominy, Dave ‘Newboy’ Payne, Gavin Willis, Ricky Hennell, Mark Crilley, Rebecca Warren (via Tim Clubb), Andrew Sharp, Jo Flanders, Neil Meadows and Andrew Hoskin. Also to Steve and Julie Pankhurst and Jane Bradley themselves, the smiling face of the nation’s favourite website.

Cheers to Stuart, Vanessa, Becke, Jamie and Gareth for the short holiday at Virgin Books.

Goodnight, sweet Tessie. We should all have such spirit.

This book was brought to you in conjunction with Clipper, Able & Cole, Ingmar Bergman and The Temptations.

Andrew Collins, November 2003

Keep reading to enjoy a sneak preview of Andrew’s sequel to

Where Did It All Go Right?

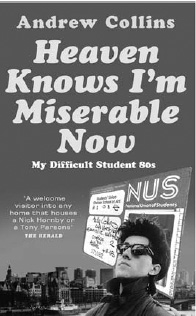

HEAVEN KNOWS I’M MISERABLE NOW

My Difficult Student 80s

Four Lovers Entwined

Well, somebody was bound to leave me a voodoo doll eventually.

It was waiting for me on the floor outside the door of Room 317 when I came home from college this afternoon. A five-inch-high black figure made from soft material, sitting there dressed in a little black hooded coat, with a safety pin prised open to form a vicious spear and thrust portentously into its belly. No note, no clues, nothing. Just this gloomy, monkish effigy.

I’ll be honest, I was spooked all through dinner. What had I done to deserve this macabre scare?

I sort of knew.

My decisive second term had since Valentine’s Day been loaded with incident, much of it romantic, most of it complicated. A Ray Cooney farce played out with trousers around ankles between floors and now, of course, a

Bergerac

-style mystery with me playing both John Nettles and the accused. If the first term had been about wiring up speakers and putting things away, the second was about painting the halls red and notching the bedpost. Getting things out.

There was something about the New Year. Just as I’d excommunicated myself from the town that had raised me, I was forced back there for three weeks at Christmas as some form of

humiliating

penance. (The halls turfed us all out during holidays, enabling them to power down the generator, rest the laundry service, lower the canteen shutters and recharge Ralph’s batteries.) Exile in Northampton simply served to galvanise my conviction that I just wasn’t made for this town. Not any more. And I couldn’t wait to get back to London.

I was able to affect the detached tourist around the old haunts, the Berni and the Bantam and the Black Lion and the Bold. The old magic was gone and I felt like Banquo’s ghost at someone else’s table. It wasn’t just me who felt disenchanted about the place. The latest craze among my old set – those who’d stayed behind – was to head off in convoys to Nottingham and Rock City to get their kicks. I saw no need to feel guilty for wanting to get out of town if they did too. Life for all of us had moved on.

I resented being back with Mum and Dad for three weeks, living under what I saw as their almost Chilean jurisdiction of repression, regularity and rules. I saw not a shred of irony in the fact that mealtimes at the halls were far more regimented than those under Mum’s roof, and that after lights out a night porter roamed the corridors to tell us to keep the noise down. Dad had written me a benignly threatening letter in early December which in précis said, ‘Get a haircut or you won’t get a Christmas’. I didn’t fully appreciate the portent of this proposal at the time, but once through the front door, with a reflexive, put-upon sigh, I booked myself in for the afternoon at Catz in town and had the worst excesses of my first term at Chelsea artfully lopped off for the sake of peace on earth and goodwill to Mumkind.

‘Happy now?’ I said, as I walked in the front door.

Actually, they did seem to be happy. In return, they gave me a car.

They gave me a

car

.

I had yet to become belligerently and intractably leftwing, so the perfect Christmas gift came wrapped with not a whiff of middle-class guilt. That followed later. By the time the

NME

and Sir Keith Joseph had turned me into a bellicose, barricade-storming socialist in the summer term, I grew self-conscious about having my own set of wheels. I would make much of the fact that my parents hadn’t

actually

given me a car – it was merely my Mum’s

old

Metro handed down when she upgraded to a Vauxhall Nova – but there was no talking round the fact that a student with a car is a rare thing indeed. You only had to look at the size of Ralph West’s car park to know that.

Maybe I could give people a lift to the barricades.

I christened my secondhand car Shake – in honour of the Cure song ‘Shake Dog Shake’ and the fact that it did just that on the M1 over 40 miles an hour, as if perhaps it was, in

Star Trek

argot, ‘breaking up’ – and I glued cut-out letters announcing its name on the blue sunstrip Simon had bought me for Christmas along with a furry steering wheel cover.

So I travelled back to London in January not by cut-price rail but hazardous, icy road, my portable tape player on the front seat stoked with The Art of Noise and Lloyd Cole & The Commotions (Kevin’s opinion of whom I don’t think I need to relate), plenty of Ritz crackers and clean underpants in the hatchback, and at least one sexual misadventure to regale Rob with when I got there. A regrettable quickie with a girl I met in the Bold on New Year’s Eve called Sandy who said I looked like Tom Bailey out of the Thompson Twins (this was deemed a compliment) and from whom I never heard again.

I joined the AA on Sunday January 6, 1985, a deceptively mundane act of form-filling that was loaded with significance – I was a big boy now. To borrow the association’s own tagline: it’s great to know you belong. It’s also great to be able to charge your friends petrol money for a lift to college every day: 20p each for the return journey (which worked out at almost £2 a week, the price of a gallon of four-star in 1985). This entrepreneurial spirit, which went down well with my Dad and would have earned me a proud pat on the head from Norman Tebbit, was no doubt stimulated by the experience of freelance work, which David Williams continued to put my way, preventing me from becoming a drain on my parents’ finances and in a roundabout way, paying them back for the car.