Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 (18 page)

Read Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 Online

Authors: James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts

Tags: #History, #Americas, #United States, #Asia, #Southeast Asia, #Europe, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #World, #Humanities, #Social Sciences, #Political Science, #International Relations, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #European, #eBook

But in 1963, as the general’s statistical cloth began to unravel, North Vietnam brought nearly 13,000 infiltrators down the Ho Chi Minh Trail that bypassed the division between North and South Vietnam by going in Laos. In 1959 and 1960 it had sent 4,500 and in 1961 it added 6,300. From 3,000 people in 1960 to 10,000 in 1961 to 17,000 in 1962, the Main Force Vietcong now stood at 35,000. Most were former Vietminh, native southerners regrouped to North Vietnam after 1954. They were highly motivated, well trained, and anxious to go home. Secret intelligence reports indicated that the Vietcong were gaining strength, that they were fielding 600- to 700-man battalions supported by communications and engineering units, and that the 9th Vietcong Infantry Division would soon be ready for full deployment.

And they were well armed. Homemade shotguns and World War II vintage rifles were a thing of the past. Between early 1962 and mid1963, MACV distributed more than 250,000 weapons to CIA and Special Forces irregular troops—M-14 carbines, shotguns, submachine guns, mortars, recoilless rifles, radios, and grenades. Most of them ended up with the Vietcong. Some ARVN outposts were particularly notorious for losing weapons. Americans called them “Vietcong PXs.” The American cornucopia of death was so reliable that in mid-1963 Vietcong commanders relayed messages north that it was easier to capture American weapons than to bring Chinese and Soviet arms down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Nor were the Vietcong having any trouble finding recruits. The Strategic Hamlet Program was a bonanza for them. Within a matter of months the Diem regime herded millions of peasants into hastily constructed hamlets that were more concentration camps than villages. Peasants were forced to build the new hamlets, dig the huge, waterfilled moats around them, string the barbed wire, and knock down their old homes. Millions of peasants left ancestral villages at gunpoint for the confinement of the strategic hamlets. The Vietcong used a simple response: “When the Diem regime falls and the Americans leave, you will be able to go home again.” The peasants listened. The Vietcong also infiltrated the Strategic Hamlet Program. Nhu gave control of the program to Colonel Pham Ngoc Thao, who ruthlessly implemented it. What Nhu did not know was that Thao was a Vietcong agent. His instructions were to be brutal in building the strategic hamlets, to alienate as many peasants as possible. He was eminently successful. According to the historian Larry Cable, “The United States had about as much effective control over the... Strategic Hamlet Program, as a heroin addict has over his habit.”

No less successful in lining up peasants behind the Vietcong was American air power. Between early 1961 and the end of 1962 air force personnel in South Vietnam increased from 250 to 2,000, and the number of monthly bombing sorties from 50 to more than 1,000. By the middle of 1963 the air force was conducting 1,500 sorties a month, dropping napalm, rockets, and heavy bombs and strafing the Vietcong. The problem, of course, was that air power was indiscriminate. Guerrillas died, to be sure, but so did peasants.

Between the bombing runs and the strategic hamlets, the Vietcong were able to recruit as many new soldiers as they could equip and supply. In 1960 main-force Vietcong soldiers had been supported by only 3,000 village and regional self-defense troops, but that number increased to more than 65,000 in late 1963. At the end of the year the communists had more than 100,000 troops—main force and militia—at their disposal.

More than anything else, the battle of Ap Bac in January 1963 exposed the limits of the American ability to control the fortunes of battle. Late in December 1962, two hundred troops from the Vietcong 514th Battalion dug in along a mile-long canal at the edge of the Plain of Reeds in Dinh Tuong Province, near the village of Ap Bac. Hidden by trees, shrubs, and tall grass, they had a clear view of the surrounding rice fields. When intelligence reports revealed the Vietcong, MACV felt it finally had an opportunity to engage the elusive enemy in a set-piece battle. More than 2,000 troops from the ARVN 7th Division, advised by Lieutenant Colonel John Paul Vann, went into battle. The operational plan was simple. Two ARVN battalions would approach from the north and south, while a company of M113 armored personnel carriers came in from the west. The eastern approaches would be left unguarded, so that if the Vietcong tried to escape, they would be destroyed by tactical air strikes and heavy artillery. In previous battles, the Vietcong had fled when they saw the M113s and CH-21 helicopters, but this time they held their positions. With small-arms fire they brought down five helicopters and nearly destroyed nine more, and they methodically killed the machine gunners on the M113s. ARVN troops refused to attack, and the ARVN command refused to reinforce them. The Vietcong escaped with twelve casualties, leaving behind two hundred dead or wounded ARVN troops and three dead American advisers.

The battle of Ap Bac had immediate repercussions. Neil Sheehan and David Halberstam were among the reporters who knew they had a story; after a year of Headway Reports, Ap Bac showed how the war was really going. The military tried, of course, to discredit the journalists. Admiral Harry Felt, commander of the United States Pacific fleet, went to Saigon after the battle and announced in a press conference: “I don’t believe what I’ve been reading in the papers. As I understand it, it was a Vietnamese victory—not a defeat, as the papers say.” Harkins nodded and agreed: “Yes, that’s right. It was a Vietnamese victory. It certainly was.” Robert McNamara’s confident proclamation, “We have definitely turned the corner toward victory,” was predictable. But the only people turning any corner were the Vietcong.

The eccentricities of Diem’s coterie hastened the deterioration brought on by the Strategic Hamlet Program. The president’s elder brother Ngo Dinh Thu, archbishop of Hue, used his political clout to augment church property. One critic charged that his requests for contributions “read like tax notices.” He bought farms, businesses, urban real estate, rental property, and rubber plantations, and he employed ARVN troops on timber and construction concessions. Ngo Dinh Can, the dictator of Hue, accumulated a fortune as head of a smuggling syndicate that shipped huge loads of rice to Hanoi and large volumes of opium throughout Asia. Ngo Dinh Luyen, the South Vietnamese ambassador in London, became a multimillionaire speculating in piasters and pounds using insider information gleaned from his brothers in Saigon. More bizarre still were the antics of Ngo Dinh Nhu. By 1963 Nhu was smoking opium every day. His ambition had long since turned into a megalomania symbolized by the Personalist Labor Revolutionary party, or Can Lao—secret police known for torture and assassination. Can Lao troops, complete with Nazi-like goose-step marches and stiff-armed salutes, enforced Nhu’s will. Madame Nhu had her own stormtroopers, a group known as the Women’s Solidarity Movement and Paramilitary Girls, which worked at stamping out evil: dancing, card playing, prostitution, divorce, and gambling. The Nhus amassed a fortune running numbers and lottery rackets, manipulating currency, and extorting money from Saigon businesses, promising “protection” in exchange for contributions. After reading a CIA report on the shenanigans, President Kennedy slammed the document down on his desk and shouted, “Those damned sons of bitches.”

President Diem’s peculiarities were fast becoming derangements. He was addicted to eighteen-hour work days and then left paperwork at the side of his cot to attend to when he woke up in the night to go to the bathroom. His mind locked into its own private world, he was afraid to leave business to others and assumed more and more duties, even personally approving all visa requests and deciding which streets got traffic lights. He gave military orders as well, not just to divisions and battalions but to companies, often not keeping their commanding officers informed of his decisions. In discussions with foreign journalists and American officials, Diem offered mind-numbing monologues of five, six, even ten hours. Visitors could not get in a single comment. Charles Mohr saved his questions for when Diem was lighting another cigarette; those were the only occasions he stopped talking. As Robert Shaplen of

The New Yorker

observed of those interviews, Diem’s “face seemed to be focused on something beyond me.... The result was an eerie feeling that I was listening to a monologue delivered at some other time and in some other place—perhaps by a character in an allegorical play.” South Vietnam was a dictatorship: Dissidents were imprisoned, tortured, or killed; elections were manipulated; the press, radio, and television were controlled; and universities were treated as vehicles for government propaganda.

The national holiday on October 26, 1962, celebrating the triumphant Diem elections in 1955, exposed the depth of Diem’s isolation. He staged an elaborate military parade through Saigon. ARVN troops and armored personnel carriers left the field late in September to get ready for the parade, much to the dismay of American advisers fighting the Vietcong. Diem invited a few members of the press corps and some foreign diplomats to join him on the stand. The parade proceeded uneventfully, except for one bizarre fact: Diem sealed off from the public the entire parade route and several city blocks. The parade wound its way along the Saigon River with no spectators, only vacant sidewalks. ARVN troops and Nhu’s secret police forced store owners to close up shop and leave their buildings. Diem wanted no contact with his people. For David Halberstam the parade was a surrealistic experience: “One felt as if he were watching a movie company filming a scene about an imaginary country.”

Resentment had long smoldered among the Buddhists who saw power, land, government jobs, and money flow to the Roman Catholics. The Buddhist political movement was led by Thich Tri Quang, an intensely nationalist monk who headed the militant United Buddhist church. Although he was not a communist, Quang had cooperated with the Vietminh in fighting the French and the Japanese. What Thich Tri Quang was able to exploit, in the name of civil liberties, was a widespread popular desire in many parts of South Vietnam to overthrow Diem, expel the United States, and restore Vietnam to its traditional moral values.

Pent-up feelings exploded on May 8, 1963, the 2,587th birthday of Gautama Buddha. Diem prohibited Buddhists from flying their religious flags during the holiday. More than 1,000 Buddhist protesters gathered at the radio station in Hue demanding revocation of the order. When they refused to disperse, ARVN troops opened fire, killing eight people and wounding dozens more. The next day 10,000 Buddhists showed up demanding an apology, repudiation of the antiflag regulation, and payments to the families of the wounded and the dead. Buddhist hunger strikes spread throughout the country, and demonstrators walked the streets in Saigon. Late in May, Ngo Dinh Can imposed martial law on Hue and patrolled the streets with armored personnel carriers, tanks, and ARVN troops. In Saigon, Ngo Dinh Nhu’s police assaulted Buddhist crowds with attack dogs and tear gas. Mandarin leaders expect obedience, not argument resolved by compromise.

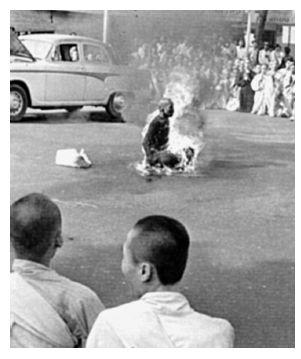

On June 11, 1963, Thich Quang Duc, a seventy-three-year-old Buddhist monk, knelt on Pham Dinh Phung street in Saigon, surrounded by Buddhist monks, nuns, and invited journalists. A colleague doused him with five gallons of gasoline, and Duc lit a match and ignited himself, burning to death in protest of the Diem regime. The picture of his motionless body burning for ten minutes spread across the world wire services. A series of Buddhist torch suicides came in rapid succession. Madame Nhu remarked that she would be “willing to provide the gasoline for the next barbecue.”

Throughout July, Ambassador Frederick Nolting pleaded with Diem to reach some accommodation with the Buddhists. Kennedy threatened to cut off economic and military assistance unless Diem acquiesced, but Diem, stiffened by Nhu’s fanatical opposition to American pressure, became more intractable. Many noncommunist South Vietnamese resented the American presence in their country, and Diem had to be careful about appearing to cave in to American pressure. In Vietnamese history, appearing as a puppet to a foreign power was political suicide. If Diem backed down, he might lose what little political support he still had.

So the assault on the Buddhists continued. Late in July, Nhu’s goon squads, many of them dressed in ARVN uniforms, placed barbed wire around hundreds of Buddhist pagodas and arrested Buddhist leaders. Two weeks later they invaded the pagodas and dispersed all meetings there. In Hue they killed thirty worshipers and wounded two hundred more at the Dieu De Pagoda. Diem arrested children for carrying antigovernment signs and closed schools. By mid-August he had jailed more than a thousand adolescents. Finally, on August 20 he imposed martial law throughout the country. The madness precipitated an intense debate in Washington. Harkins and Nolting insisted that the war was going well and that victory was still within reach. Maxwell Taylor, Robert McNamara, Walt Rostow, and Dean Rusk agreed. But Senator Mike Mansfield insisted that defeat, not victory, was just around the corner. At a meeting of the National Security Council on August 31, Paul Kattenburg, a State Department official who headed the Interdepartmental Working Group on Vietnam, suggested that the United States should “get out while the getting is good.” Unfortunately for Kattenburg, his boss was at the meeting. “We will not,” Dean Rusk insisted, “pull out until the war is won.” Kattenburg kept his mouth shut, but his State Department career was over. Rusk posted him to Guyana.