Why Growth Matters (10 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Then again, the political and social implications of any increase in appropriately measured inequality would depend on the social context in which it occurs. Thus, if inequality increases and the rich spend money on conspicuous consumption, that could become socially explosive. But if mobility is high, the poor may react by celebrating the conspicuous inequality rather than resenting it, because they think that they too may someday “make it big” in that way.

Keeping these caveats in mind, consider some general economic arguments that bear on income distribution between the rich and the poor in an economy such as India's. First, some forms of inequality can be expected to rise in a rapidly growing economy. Growth involves wealth creation. Insofar as a small number of entrepreneurs lead this wealth creation, and those creating wealth are unlikely to redistribute all of it in an act of altruism, disparity among the richest and the rest of the population in both income and expenditure is likely to rise.

Likewise, rapid growth is often led by the formation of a small number of agglomerations (i.e., concentrations of economic activity in limited geographical areas), which generally form in urban centers, leading to urbanârural as well as regional inequality. On the other hand, in a labor-abundant economy, pro-growth policies are also expected to lead to specialization in the labor-intensive goods, which raises employment and wages of the poor. The poor can move from lower-paid jobs in the

countryside to higher-paid jobs in rapidly growing urban agglomerations, thereby producing less inequality.

Against this background, what has been the Indian experience? As it happens, the evidence we discuss below shows that contrary to widespread impressions, inequality measures do not point to an unambiguously rising trend in inequality.

Thus, Krishna and Sethupathy (2012) have recently measured inequality in India, using the household expenditure survey data from the NSS rounds conducted in 1987â1988, 1993â1994, 1999â2000, and 2004â2005.

2

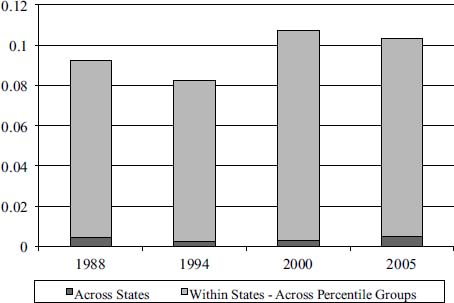

They show that inequality between states and between urban and rural areas is dwarfed by inequality among households within each of these aggregates. For example, inequality within states accounts for more than 90 percent of the total inequality over the country (see

Figure 4.1

). Inequality between states accounts for less than 10 percent of the total inequality across the country. Likewise, inequality within rural and urban areas accounts for 90 percent or more of the total inequality across the nation.

Importantly, the overall inequality exhibits only modest variation over the period, rising slightly between 1988 and 1994 and again between 1994 and 2000, but by 2005 dropping to a level slightly above that in 1988 (see

Figure 4.1

). Inequality trends within states mirror the national experience: it rose between 1994 and 2000 and then fell between 2000 and 2005 in most states. Indeed, between 2000 and 2005, only four statesâMizoram, Maharashtra, Orissa, and Haryanaâexperienced significant increases in inequality. The picture is almost exactly the same for rural and urban areas within states; the vast majority experienced rising inequality between 1994 and 2000 but falling inequality between 2000 and 2005.

The results of other researchers, comprehensively surveyed by Weisskopf (2011), echo the basic message of Krishna and Sethupathy that, rather than exhibit secular trend, inequality has gone up and down during the growth process with at most a modest net rise since the 1980s. These researchers rely on the Gini coefficient, which usually varies by two or three percentage points, changing only rarely by five percentage points. What is interesting, however, is that some researchers have gone on to interpret these changes as representing “significant” or “pervasive” increase in inequality.

Figure 4.1. Changes in inequality over time and within households versus across states

Source: Krishna and Sethupathy (2012, Figure 6.9)

Thus, Deaton and Drèze (2002) report estimates that exhibit no clear trend in rural inequality and a small increase in urban inequality. But in the text of their paper, they surprisingly conclude, “To sum up, except for the absence of clear evidence of rising intra-rural inequality within states, we find strong indications of a pervasive increase in economic inequality in the nineties. This is a new development in the Indian economy: until 1993â94, the all-India Gini coefficients of per capita consumer expenditure in rural and urban areas were fairly stable” (p. 3740). Evidently their stark conclusion is not consistent with their statistical findings.

In almost an identical spirit, Weisskopf (2011) quotes Patia Topalova approvingly as stating that “all measures point to significant increase in overall inequality in the 1990s” (p. 46). Yet, the Gini coefficient calculated by Topalova and reported by Weisskopf changes from 31.9 in 1983â1984 to just 30.3 in 1993â1994 and 32.5 in 2004â2005. One

would think that the difference between 31.9 and 32.5, which may not even be statistically significant, would hardly warrant the inference that there has been a

significant

increase in inequality.

3

An extra dividend from Krishna and Sethupathy's analysis is the finding that there is no correlation between the change in inequality across households within states and the change in state-level measures of tariff and non-tariff protection. Trade openness is not linked to increased inequality.

The critics of the reforms have also raised a different concern: that growth has been uneven across states and that this has resulted in increased inequality among them. This is correct since richer states have grown faster than the poorer states

on average

. This phenomenon may have political salience if it leads to resentment by the states lagging behind, which are poor to begin with. But four qualifying facts must be kept in view.

First, as Panagariya (2010a) and Chakraborty et al. (2011) show, the years 2003â2004 to 2010â2011 have seen nearly all states growing significantly faster than they did in any prior period. Therefore, the rise in interstate inequality does not reflect the poorer states' remaining poor or being further impoverished. Instead, it represents the richer states growing faster than the poorer states in an environment in which all states are growing faster.

Second, two of the poorer statesâBihar and Orissaâare among the fastest-growing states today. Their success shows that when the national policies are conducive to growth (as they have been after the significant reforms began) and some of the states grow rapidly, the door to poorer states' achieving similar success is also opened wider. As Bhagwati and Panagariya (2004) and Panagariya (2009a) have argued and Gupta and Panagariya (2012) have analyzed in detail, there will likely be a diffusion effect: when the rest of the economy is growing rapidly, the electorate in the poorer states will demand more from its leaders, prompting policy changes that increase prosperity. Both Bihar and Orissa have elected and reelected chief ministers who have performed well.

Third, faster growth in some states opens the scope for larger-scale redistribution programs in favor of poorer states. A program such as the

National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, which benefits the poorer states proportionately more, would not be feasible without certain states' having large enough incomes to make the necessary revenues available.

Finally, labor is not immobile across states. It is well known that labor from Bihar has traditionally moved to Mumbai and Kolkata for jobs, as have people from the Punjab and from the hills. That means that faster growth will attract migrants from the slower-growth states and regions, so that the prosperity (as distinct from growth) will diffuse to the slower-growth areas through the usual channels, such as remittances.

A further dimension of inequality relates to the socially disadvantaged groups. Once again, critics often assert that the income differences between the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe on the one hand and non-scheduled castes on the other have gone up during the years of rapid growth. But in a comprehensive analysis, Hnatkovska, Lahiri, and Paul (2012) show that such claims are not supported by empirical evidence.

Using Employment-Unemployment Survey data from the NSS rounds conducted in 1983, 1987â1988, 1993â1994, 1999â2000, and 2004â2005, they show that the wages of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes have been converging to those of non-scheduled castes since 1983. They demonstrate also that differential education levels of the two groups drive most of this convergence. Likewise, the occupation structure of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes has also been converging toward that of non-scheduled castes. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes have been able to take advantage of the rapid growth and structural changes in India during the post-reform period and have rapidly narrowed their huge historical economic disparities with non-scheduled castes and tribes.

.

The emergence of billionaires and the exposure of a few mega-corruption cases have led some, especially Sinha and Varshney (2011), to argue that

India has now entered a Gilded Age much like the United States in the late nineteenth century.

4

During this period in the United States, four main strands of criticism were rampant. The first was that American business elites had succumbed to “gross materialism,” which was manifest in conspicuous consumption and crass displays of wealth. Second, this was made possible by the accumulation of great wealth by the likes of John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, and indeed many others, while the vast masses toiled for minuscule wages. Third, these tycoons were not “captains of industry” to be admired but were rather “robber barons” who had built their fortunes on abusive business practices and high-handed suppression of attempts at unionizing labor. Fourth, (in modern terminology) there was a business-political complex, such that these robber barons and corrupt politicians had greased one another's palms and defrauded the nation.

Mark Twain's 1873 novel with Charles Dudley Warner was titled

The Gilded Age

, a phrase that gained wide circulation.

5

The book was a reaction to the excesses that accompanied the remarkable growth of the American economy as the production of iron and steel took off with rail transport expanding rapidly to bring primary resources from the expanding western frontier to the east. Oil and banking expanded at an unprecedented pace as well, leading to massive fortunes for tycoons. The vignettes from this Gilded Age amply illustrate the criticisms that attended the extraordinary growth.

Lavish parties were a way of life for the nouveaux riches. An account of the time says: “Sherry's Restaurant hosted formal horseback dinners for the New York Riding Club. Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish once threw a dinner party to honor her dog who arrived sporting a $15,000 diamond collar.”

6

There was also a populist resentment of the extreme wealth contrasted with the tragic reality of slums and subsistence wages in the overcrowded tenements in the growing urban towns and cities. The general perception, reflecting that contrast, was that while the rich wore pearls, the poor were in rags. There was growing talk of retribution through emerging violence: fears grew of “carnivals of revenge.”

Against this backdrop, labor began to organize against long hours and low wages, and the robber barons occasionally reacted by breaking the strikes brutally. Thus, even Andrew Carnegie, who professed sympathy for the poor, reacted to the Homestead Strike of 1892 by supporting his manager, Henry Frick, who locked out workers and hired Pinkerton musclemen to threaten the strikers. This was no isolated incident.

The offending titans also operated in a governance vacuum regarding business practices they used to gain monopoly control. Notorious for such business practices was John D. Rockefeller of Standard Oil Company, who in 1870 turned his company into one of the nation's first notorious monopolistic trusts. Antitrust legislation came later: the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 and the later, tougher, and more effective Clayton Anti-Trust Act of 1914.

The era was also marked by corruption at the highest levels of government, including the president, but more typically at the levels of local governance where, as today, businesses and governments shared the spoils from local grants of cash subsidies and land gifts, presumably for a “social purpose” (such as constructing a railroad) but in fact for the sole purpose of defrauding the commonwealth.

Is India today in such a Gilded Age? There are superficial similarities, for sure. True, in the same way that fast growth in the nineteenth-century United States created the Vanderbilts, Carnegies, Rockefellers, and Morgans, it has created a large number of billionaires in India. Again, like the robber barons of the American Gilded Age, Indian billionaires have tilted the playing field to their advantage through securing mining and land resources, seeking regulations favorable to them, and blocking foreign entry. But the similarity ends there.

7