Why Growth Matters (8 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Figure 3.2. The proportion of the population living below the official poverty line, 1951â1952 to 1973â1974

Source: Authors' construction based on estimates in Dah, Guarov, 1998. “Poverty in India and Indian States: An Update,” Discussion Paper No. 47, International Food Policy Research Institue (July)

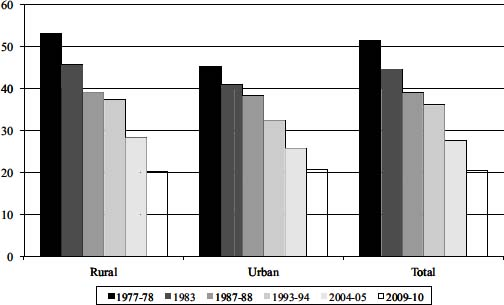

Figure 3.3

, which shows the poverty ratio in rural and urban India and the country as a whole at various points between 1977â1978 and 2009â2010 presents a sharp contrast to

Figure 3.2

.

11

Once the stranglehold of controls was loosened and reforms took root, growth accelerated and poverty fell in both rural and urban India and nationally. One can argue about the

level

of poverty since it depends on where precisely we draw the poverty line, but one cannot argue about the declining

trend

in it. Indeed, official estimates for 1993â1994, 2004â2005, and 2009â2010 are at a higher poverty line and these also show a declining trend in both rural and urban India.

Recognizing the compelling nature of the evidence on the decline in poverty under reforms and accelerated growth, critics have shifted ground. They now argue that the decline during the post-reform era has not accelerated and even slowed down relative to the pre-reform era. For this, they compare the annual percentage-point decline between 1983 and 1993â1994 and that between 1993â1994 and 2004â2005. But this argument has two serious problems.

Figure 3.3. Poverty ratio in rural and urban India, 1977â1978 to 2009â2010

Source: Authors' construction based on estimates in Mukim and Panagariya (2013)

First, true comparison of pre- and post-reform performance is not the one that critics draw but rather the one between the first three decades, spanning 1950â1980, and the past three decades, 1980â2010. Even though liberalizing reforms in India became more systematic in 1991, they were already under way during the 1980s.

Second, and a tough nut for the critics to crack, is the poverty estimate based on the latest expenditure survey, conducted in 2009â2010, which captures the effect of the 8.7 percent growth during 2005â2006 to 2009â2010. This estimate shows that poverty during these five years fell at a rate far exceeding that in any other period. Indeed, the acceleration during this period is so large that when we combine it with the earlier period and compute the average percentage-point decline per year during 1993â1994 to 2009â2010, this number turns out to be larger than during 1983 to 1993â1994, the period critics favor the most.

12

But some critics reject the evidence of declining poverty by arguing that there has not been a major dent in the

absolute

number of people living below the poverty line and that this fact undermines the claim that poverty fell after the reforms. According to the official estimates provided by the Planning Commission, at the traditional poverty line, the India-wide absolute number of poor was 323 million in 1983, 320 million in 1993â1994, and 302 million in 2004â2005. Presumably, therefore, the number of poor has at best declined marginally.

13

However, the practice, once popularized by the World Bank, of citing the absolute number of poor makes for a flawed method of measuring poverty in the face of a rising population.

14

This approach to measuring poverty will in fact downplay the decline in poverty because it does not distinguish between changes in the absolute and in the relative or proportionate number of poor.

The use of absolute number of poor biases the poverty measure upward. (One might cynically speculate that the biased measure was pop

ular at the World Bank and diffused to the client nations, so as to increase the alarm over poverty and bolster the critiques of a reforms-oriented development strategy.)

15

Shifting, however, to the “proportionate” measure of poverty, we get a more meaningful idea of what happened in India. According to official poverty estimates, provided by the Planning Commission, the proportion of the population below the poverty line in India fell from 44.5 percent in 1983 to 27.5 percent in 2004â2005. During the same period, population rose by approximately 374 million. Unless you make the ludicrous assumption that the entire net addition of 374 million to the population was non-poor, a reasonable expectation would be that in the absence of an effective poverty-alleviation strategy, the poor would have been 44.5 percent of the additional 374 million people, or a further 166.5 million poor people.

16

Adding this number to the original 323 million poor in 1983, this would have meant a total of 489.5 million poor people in 2004â2005. But since the actual number of poor people in 2004â2005 was only 302 million, this suggests the exit of 187.5 million people from poverty.

This substantial decline is properly captured by what economists call the “poverty ratio,” which fell to 27.5 percent in 2004â2005 from 44.5 percent in 1983. This clearly demonstrates the absurdity of the contention that the unchanged absolute number of poor people is equivalent to no change in poverty.

A final form in which some critics make the argument that the reforms have not helped the poor is by citing continuing or even increased poverty among certain individuals or groups of individuals. But this will not work either since we discuss below that poverty has gone down among all broad-based groups, such as the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, and across all states.

There is no doubt that there are many who were poor prior to the reforms and who remain so today. Nor can we rule out the possibility that reforms have impoverished some individuals, for example, when they are displaced from land to make way for alternative activities without proper compensation.

17

However, this approach to the criticism of reforms is ill conceived since we can measure the efficacy of a set of policies only at some

aggregate level, even when we disaggregate the effects by groups such as the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (the impact on whom we examine in Myth 3.3 below). We know of no policy that makes everyone within each disaggregated group better off and hurts literally no one.

The reality for the critics of the reforms is stark: in regard to poverty reduction, the regime of socialist policies did far less good for (and indeed even inflicted harm on) the poor and the underprivileged groups than turned out to be the case under the regime of reformed policies. India ultimately moved away from the old policies precisely because those policies, with their deleterious effect on economic performance, had failed to deliver on poverty reduction and other social goals.

.

Some NGOs and journalists as well as international organizations argue that the reform-led growth may have reduced poverty overall but it has not helped bring down poverty among the socially disadvantaged groups, principally the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes but possibly also Other Backward Castes (OBC).

For example, a submission by the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights to the House of Commons of the UK Parliament, published on January 14, 2011, states, “In spite of high economic growth rate the poverty rate among excluded communities in India has increased, coupled with the insecurity of livelihoods.”

18

In a similar vein, writing in the

Financial Chronicle

(December 29, 2010), journalist Praful Bidwai argues, “Rising inequalities highlight what is wrong with India's growth trajectory, driven as it is by elite consumption and sectoral imbalances,

which exclude disadvantaged groups from the benefit of rising GDP

, while aggravating income disparities” (emphasis added).

19

Most strikingly, even the World Bank has joined the chorus alleging that growth in India has done precious little for the tribal population of the country. A recent country brief by the bank puts the matter in these stark terms: “India is widely considered a success story in terms of

growth and poverty reduction. In just over two decades, national poverty rates have fallen by more than 20 percentage points, from 45.6 percent in 1983 to 27.5 percent in 2004â05. However it is widely acknowledged that growth has not touched everyone equitably and that many groups are left behind amid improving living standards. Among them are tribal groups identified by the Constitution as Scheduled Tribes.”

20

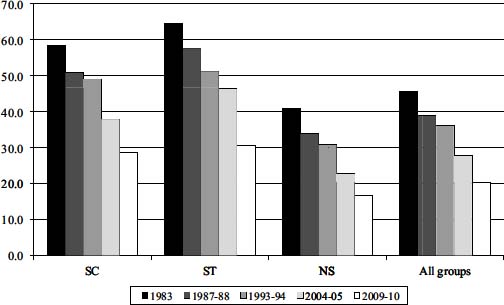

Once again, there is now irrefutable evidence that sustained growth alongside liberalizing reforms has reduced poverty not just among the better-off castes but across all broadly defined groups. It is true that the poverty ratios were and still remain significantly higher among the disadvantaged groups, reflecting historical injustices, but it is not true that these groups have not benefited from the recent growth. Indeed, evidence along all dimensions shows the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes gaining alongside the OBC and “forward” castes.

Mukim and Panagariya (2013) strikingly show that poverty fell for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes between every pair of successive surveys in rural and urban areas (see

Figure 3.4

). For the Scheduled Castes, the nationwide poverty ratio fell from 58.5 percent in 1983 to 48.9 percent in 1993â1994, 38 percent in 2004â2005, and 28.6 percent in 2009â2010. For the Scheduled Tribes, the ratio fell from 64.4 percent in 1983 to 51.2 percent in 1993â1994, to 46.3 percent in 2004â2005, and to 30.7 percent in 2009â2010. The authors also calculate the poverty ratios by states and find that they fell in all major states between 1983 and 2009â2010.

An extremely important recent development is the significantly larger decline in poverty among the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes relative to non-scheduled castes during the latest high-growth phase. Poverty for the Scheduled Castes fell by 9.4 percentage points and that for the Scheduled Tribes by a gigantic 15.3 percentage points relative to 6 percentage points for non-scheduled castes between 2004â2005 and 2009â2010. The disadvantaged groups by definition have had much higher poverty rates than other groups, but the gap has finally begun to be bridged decisively.

21

There is an impression among some scholars that growth acceleration has not helped the Scheduled Tribes. This impression has derived partially from the existence of the Maoist insurgency in certain regions where the tribes are concentrated and partially from a sense that when displacement happens from projects involving mineral extraction, tribes are not adequately compensated. While the adverse impact of these factors on the tribes can scarcely be denied, the evidence of the decline in poverty among the Scheduled Tribes is unequivocal. In this regard, two factors must be kept in mind. First, while the beginning of the poverty decline can be traced to the early 1980s, as demonstrated by

Figure 3.3

, the Maoist insurgency and even the acceleration in mineral extraction activity are of more recent origin. And second, the states with the largest populations of Scheduled Tribes, which include Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and Gujarat, have not been hotbeds of the Maoist insurgency.

Figure 3.4. Evolution of the poverty ratio for various social groups

Source: See

Figure 3.3

Finally, we may also briefly mention the trends in poverty by religious groups. Here as well, estimates by Mukim and Panagariya (2013) show declining levels across all groups. In particular, they show poverty among Muslims declining from 52.2 percent in 1983 to 25.8 percent in 2009â2010, with the largest declineâ9.7 percentage pointsâcoming between 2004â2005 and 2009â2010.

Dehejia and Panagariya (2012a) take a different route to analyzing the impact of liberalization on different social groups. They consider the status of entrepreneurship among the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe groups in the service sectors, using the survey data gathered by the National Sample Survey Organization in 2001â2002 and 2006â2007.

22

They find for entrepreneurship a pattern very similar to the one found by Mukim and Panagariya (2013) for poverty. The share of each of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe groups according to the value added and the number of workers employed in the enterprises was and remains well below its corresponding share in the population, reflecting the historical injustices. But each social group experiences healthy growth in the value added and in the number of workers employed in the enterprises owned by its members.

23