Why Growth Matters (11 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

The conditions characterizing the American Gilded Age and current-day India are vastly different. At the beginning of the Gilded Age, the dominant economic philosophy in the United States was laissez-faire. There was virtually no effective regulatory, labor, or social legislation at the federal level. Two key pieces of regulatory legislationâthe Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which aimed to limit the monopoly power of the railways, and the Sherman Act of 1890, which provided for antitrust

action against businessesâwere enacted during this period. Key laws providing protection to industrial labor, the poor, and the elderly came much later. With rare exceptions, only white males enjoyed voting rights.

In contrast, post-reform India and its growth explosion have been preceded by several decades of a command-and-control system complemented by stringent legislation in favor of industrial workers so that it is impossible to have business tycoons breaking strikes the way the American robber barons did. India, it may be recalled, has had a long-standing national commitment to eradicating poverty and achieving universal adult suffrage since independence. The country has all elements of a liberal democracy with the poor and the underprivileged having access to effective politics at the ballot box.

The economic reforms have allowed freer play to private entrepreneurs but can hardly be characterized as laissez-faire. Railways remain a public-sector monopoly and the government remains a major player in such key sectors as steel, coal, petroleum, and engineering goods. Despite private-sector entry in airlines, telecom, insurance, and electricity, the public-sector players have remained active. In banking, the role of domestic and foreign private players has been expanded but the public sector again remains dominant. And several sectoral regulatory agencies, topped by an all-encompassing Competition Commission, oversee business practices.

Whereas during America's Gilded Age major sectors such as steel, oil, sugar, meatpacking, and the manufacture of agriculture machinery came to be dominated by “trusts,” the opposite is true in India today. There are multiple domestic firms within many sectors, competing against one another as well as with imports and foreign investors. Increased competitive pressures have led to reduced prices and improved quality of products and services in such diverse sectors as airlines, telecommunications, automobiles, two-wheelers, refrigerators, and air conditioners.

The treatment of industrial workers in India today stands in sharp contrast to that in late nineteenth-century America. During the Gilded Age, factory workers toiled sixty-hour weeks without pensions, compensation for job-related injuries, or insurance against layoffs. In contrast to

the strikebreaking actions of the robber barons at the Homestead Steel Mill in 1892 and George Pullman's railroad in 1894, labor laws in India provide a high degree of protection to industrial workers.

Finally, whereas the state provided no protection to those at the bottom of the income distribution, including farmers in the United States during its Gilded Age, the government in present-day India is sensitive to the fate of the poor. Indeed, growth and the social programs it has made feasible have helped bring down poverty significantly. The changes have also benefited the underprivileged groups, as we have already documented, and as we noted, there are now a handful of Dalit

crorepatis

.

But what about the corruption? How does today's India compare to America's Gilded Age? Critics contend that the post-reform era has been driven by crony capitalism. This implies that Indian entrepreneurs have accumulated wealth mostly by redistributing it in their favor through outright fraud in collaboration with politicians, rather than by creating it.

8

But the allegation is not persuasive. Unlike Mexico, for instance, where the billionaire Carlos Slim Helú has used every conceivable means to generate monopoly profits for himself, most Indian entrepreneurs have become rich by creating wealth while operating in a highly competitive market. Recent empirical work by Alfaro and Chari (2012) also points to the existence of a highly competitive market in India with substantial entry of new firms on the margin. To be sure, one can find examples such as those of the Reddy brothers, who, according to their recent indictment, have accumulated wealth from illegal mining; but that is not the case with the vast majority of Indian entrepreneurs from the information technology, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, or engineering goods industries.

So, while the American Gilded Age produced Rockefeller and Vanderbilt, India today has given rise to Narayana Murthy of INFOSYS, Azim Premji of WIPRO, and Uday Kotak of Kotak Mahindra Bank. There is not a hint of corruption or shady practices among these successful tycoons. All of them are associated with extensive engagement with society, and have embraced corporate social responsibility and private social responsibility. Whereas Carnegie and Rockefeller gave away their fortunes on their death, the Indian tycoons have given away massive

sums of money even as they have earned them. Besides, their lifestyles are simple, not extravagant.

While the tycoon Mukesh Ambani has built a much-condemned high-rise in Mumbai, the display of personal wealth and gross materialism is far less rampant in India than in nineteenth-century America or in the New York of the 1970s prior to the current crisis and even after the financial sector's recovery. Perhaps the worst displays take the form of flamboyant and unseemly weddings costing millions, but that is a long-standing cultural tradition.

While, therefore, India is not a throwback to the American Gilded Age, one might ask: What about China? Here the parallel is closer. Union rights are nonexistent; ostentatious displays of wealth are common; and there is little attempt at corporate and personal social responsibility. So here again India scores against China and handsomely at that.

Reforms and Their Impact on Health and Education

T

here is one final area of criticism that has been leveled at the reform programs that have liberalized the economy and promoted growth: that they have failed to promote education and health. Critics have suggested that India lags behind much poorer countries in these areas; that states such as Kerala, which chose an alternative path, have performed much better; and that states such as Gujarat that have relied on growth have fallen short of satisfactory progress. But these assertions are little more than myths that fail to stand up to careful analysis and examination of data.

.

Recent focus of the media on child nutrition indicators, which place India below virtually all sub-Saharan African countries, has created the widely shared impression that India has performed poorly not just in nutrition but in health

in general

relative to these countries.

On the one hand, India is compared by the critics with much richer China and to significantly poorer Bangladesh to drive home the message that whether one takes rich or poor countries for comparison, India is a serious laggard in health achievements despite growth and successful

poverty alleviation.

1

But these inferences are plain wrong. India is by no stretch of the imagination an exceptional underachiever in health generally. In fact, India is hardly out of line with other countries with similar per capita income levels. Moreover, when countries with similar or lower per capita incomes outperform India along a specific indicator, such as life expectancy, it is often because they started well ahead in the race. Superior past achievements may continue to ensure high current

levels

of indicators despite poor achievements in more recent decades. Progress over a given period must be judged by

the gains

made during that period.

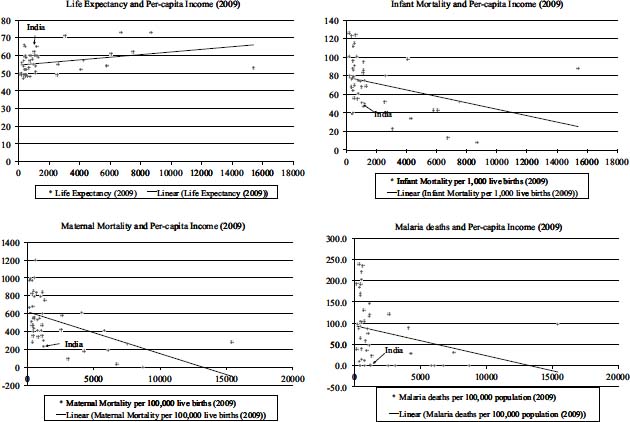

At the outset, we should dispel any lingering doubts about India's having done poorly relative to the countries in sub-Saharan Africa in terms of vital statistics in the context of its per capita income. In

Figure 5.1

we show the position of India relative to that of all sub-Saharan African countries along four indicators of health plotted against per capita income in 2009: life expectancy, infant mortality, maternal mortality, and deaths due to malaria. As is readily seen, India scores very well relative to the countries with the same per capita income or less and, indeed, in many cases relative to countries with higher per capita income as well.

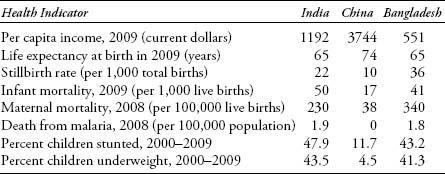

But how does India compare with the critics' favorite countries, Bangladesh and China?

Table 5.1

provides vital statistics for these countries and India, as reported in the 2011 World Health Organization (WHO) publication.

Take Bangladesh first. Without discounting its achievements, we must deflate them relative to those of India, refuting the unwarranted encomiums for Bangladesh and the exaggerated criticisms directed at India.

The performance of Bangladesh relative to that of India in terms of health indicators is significantly more equivocal than has been reported by the critics. Indians and Bangladeshis enjoy the same life expectancy at birth. Bangladesh has a lower infant mortality rate than India (41 per 1,000 live births against the latter's 50) but its rate of stillbirth more than offsets the difference (36 per 1,000 births against India's 22): an inconvenient fact that almost all observers emphasizing the lower infant mortality in Bangladesh ignore.

2

The maternal mortality rate in Bangladesh is, in fact, much higher than in India. Mortality due to malaria is similar while Bangladesh edges out India only marginally on nutrition indicators.

Figure 5.1. Comparing India to the countries in sub-Saharan Africa in terms of life expectancy, infant mortality, maternal mortality, and deaths due to malaria

Source: World Development Indicators for per capita incomes and WHO (2011) for other indicators

Table 5.1. Selected indicators: Bangladesh, China, and India, 2009

Source: World Development Indicators of the World Bank for per capita GDP and World Health Organization (2011) for the remaining indicators

In comparing Bangladesh and India, we must also take into account history. According to the United Nations (World Population Prospects, the 2010 revision), life expectancy in Bangladesh during 1950â1955 was forty-five years compared to just thirty-eight years in India. The 1971 war led to a major dip in most health indicators of Bangladesh but they recovered in the following decades. At least some of the accelerated progress Bangladesh has achieved during the 1980s and beyond is therefore to be attributed to its return to the initial conditions.

This point is reinforced when we compare Bangladesh to West Bengal, with which it has a shared history and geography. Not only are the two entities located in the same region, but they also were once part of the same larger state in preindependence India. It turns out that West Bengal outperforms Bangladesh in terms of health indicators. Already during 2002â2006, it enjoyed a life expectancy at birth of sixty-five years. And its infant mortality rate of 33 per 1,000 live births in 2009 and maternal mortality of 141 during 2004â2006 were considerably lower than the corresponding rates reported for Bangladesh in

Table 5.1

.

3

Turn next to the IndiaâChina comparison. Some critics of Indian performance on health argue that despite acceleration in growth since the 1980s, India has done poorly relative to China in improving its health indicators. Such assertions are misleading for at least two reasons.

First, growth in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s has been much faster in China than in India.

4

And second, like Bangladesh, China has enjoyed a historical advantage over India. For example, China had already gained much of its lead over India in life expectancy by the early 1970s (see

Figure 5.2

).

Indeed, the gap in life expectancy between China and India has steadily declined in recent decades, falling from 13.2 years at its peak in 1971 to 9.3 years in 2009. It is ironic that Amartya Sen, who has been criticizing India for its poor achievements in health vis-Ã -vis China, himself made this point in 2005: “The gap between India and China has gone from 14 years to seven [since 1979] because of [China] moving from a Canada-like system to a U.S.-like system.”

5