Why Growth Matters (15 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

First we look at the problems afflicting the data on suicides, whether overall or among farmers. Next we address whether overall and farmer suicides correlate with Indian reforms generally. We then assess whether the new BT seeds have resulted in accelerated farmer suicides.

At the outset, data on suicides in general and by farmers in particular are not entirely reliable. In the latter case the most commonly used series is also very short. The source on which most scholars rely is the annual publication

Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India

by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Ministry of Home Affairs. According to Nagaraj (2008), the chiefs of police of all states, union territories, and mega cities furnish data to NCRB, which in turn compiles and publishes them. Although NCRB has published the basic data since 1967, it began to provide details that allow farmer suicides to be identified only in 1995. But the data for 1995 and 1996 are incomplete; the consistent series began in 1997.

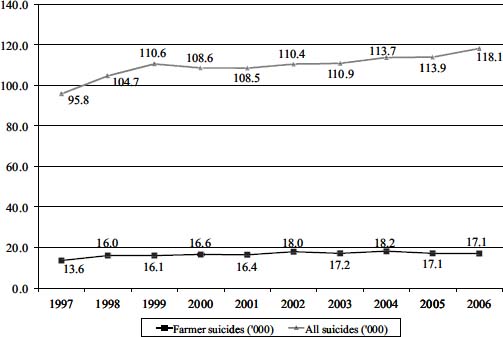

Figure 6.1

plots the data reported by Nagaraj (2008). First we observe that since the data begin only in 1997, strictly speaking, we cannot connect suicides to reforms generally. To do so convincingly, we must have the pre-reform data going back to at least the 1970s and 1980s. It is quite remarkable that critics of the Indian reforms have ignored this simple fact and claimed such a link as if farmer suicides today were a new phenomenon (absent prior to their explicit identification by NCRB beginning in 1995).

2

Second, even if we insisted on trying to forge a connection with whatever little data we do have, we might hypothesize that since major additional reforms took place in the late 1990s and early 2000s and growth accelerated in 2003â2004, we still might make a connection by comparing suicide rates prior to 2003 and later. But whereas the general suicide rates do show a mildly rising trend in the last three years shown, farmer suicides rose in 2004 but fell in 2005 and 2006, dropping below their 2002 level.

Finally and most intriguingly, we may compare the levels of farmer suicides relative to suicides in the general population. At peak, reached in 2002, they were 16.3 percent of the latter. But at least half of the Indian workforce is engaged in farming. This fact points to a much lower suicide rate per 100,000 individuals for farmers than in the general population. Given this fact, one might well be agitated, less about the farmer suicides than about why the suicide rate in the general population is so much higher and how we could bring it down to the levels prevailing among farmers. On the other hand, the difference is so huge between the measured farmer and non-farmer suicide rates that one may question the validity of the data.

3

Figure 6.1. Suicides in the general population and among farmers

Source: Authors' construction using data in Nagaraj (2008)

But while there is no evidence for the link between reforms and suicides in general and farmer suicides in particular, it leaves open the narrower and more explosive issue of whether the introduction of BT seeds in cotton in 2002 led to an acceleration of suicides among farmers.

Contrary to what the critics assert, however, it is evident from

Figure 6.1

that farmer suicide rates show no accelerating trend from 2002. Yet, according to Gruere, Mehta-Bhatt, and Sengupta (2008, Figure 11), the area under BT cotton expanded from nil in 2002 to more than 3.5 million

hectares in 2006. These authors also look at individual states, such as Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, and fail to find any correlation between rising trends in farmer suicides and the expansion of the area cultivated under BT cotton.

Gujarat provides the most compelling example from this perspective. It was the first state to adopt BT cotton and the third largest after Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. By 2006, 25 percent of its total area under cotton had come under BT cotton. At the same time, it has the lowest numbers of reported farmer suicides at approximately five hundred per year, with the number slightly lower on average during 2003â2006 than in the preceding five years.

4

Then again, the causes of suicides are many. This is so even in the case of farmer suicides. It is therefore unlikely that a single cause like BT seeds would emerge as the main factor. A study by Deshpande (2002) that examined in depth ninety-nine cases of farmer suicides in Karnataka underlines the need for this caution. Deshpande extensively interviewed the friends and relatives of the victims and considered a long list of proximate causes, including the volume and terms of debt, crop failures, dowry burden, and drinking problems. He did not find a single case in which one reason accounted for the fateful event. On average, there were three or four reasons in each case. Farm-related reasons get cited only approximately 25 percent of the time in suicide. Even more surprisingly, he notes, “Debt burden and the price crash, which have been quite commonly referred as important factors by the media and public personalities, happens to score 6 per cent probability of being one of the prominent reasons for suicides along with other reasons” (p. 2608).

Nonetheless, we may observe that in the few regions where farmer suicides have followed the introduction of BT seeds, the cause could well be that small, highly indebted farmers are bamboozled by salesmen employed by the corporations producing the seeds into buying and using the seeds, using high-cost loans, on the promise that this investment will produce high returns that will relieve the debts under which they labor. This is then a casino-type bet. When that fails, for reasons such as poorly

implemented planting or adapting the new seeds to local conditions or simply a bad harvest, the distress rises to a level that prompts a suicide.

It is noteworthy that the earlier green revolution was not a result of privately invented and propagated seeds, and a proper government-financed and -organized extension service for which Dr. M. S. Swaminathan deservedly became famous complemented it. This also meant that the larger farms, with more resources and ability to take the risk of failure used the new seeds, while the small farmers did not.

This time around, in the few regions where farmer suicides have occurred, the small farmers who have been misled by the salesmen peddling the new seeds unscrupulously (much like the salesmen who were peddling risky housing mortgages to undeserving mortgage buyers in the United States and feeding the housing bubble whose collapse forced these victims into distressed sales) are the victims. The answer there appears then to be a regulation of these salesmen and measures, such as the setting up of an extension service for the BT seeds whose cost should be charged to the corporations selling the BT seeds.

.

While we have seen that the charge that reforms have led to the Gilded Age in India is inappropriate, a separate criticism is that corruption is the result of the reforms: a charge that recurs in other countries that have embraced reforms.

A common refrain of the left-wing critics is that the post-1991 “neoliberal” reforms have led to exponential growth in corruption. For example, in the article “Economic Reforms: Fountain Head of Corruption” in the

New Age Weekly

, the central organ of the Communist Party of India, R. S. Yadav writes:

The early stage of [the] liberalization process in the 1980s was accompanied by [the] Bofors scandal which for the first time in independent India put up the prime minister and the prime minister's

office in the center of the scandal. After the full fledged adoption of neo-liberal reforms in 1991, the country came across a wave of scams and scandals, every scandal bigger in magnitude, and more bold, and involved people at the helm of governance, administration and industry.

5

The young among critics such as these are blissfully ignorant of history, while the old probably suffer from amnesia.

6

The near-absence of corruption was among the hallmarks of the Indian political virtue in the 1950s.

7

Corruption broke out not with the liberal reforms of the 1980s, but under the license-permit raj that peaked in the 1970s during the socialist-era policies of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. With the government controlling the manufacture, distribution, and price of numerous major commodities, bribes became virtually the only means of accessing the latter within a reasonable time frame. Thus, for example, if you wanted a phone, car, or scooter, you had to choose between a many-years-long queue and a bribe. If you were among the lucky few to have a phone, a bribe was still necessary to receive the dial tone. If you wanted an airline ticket or a reserved railway seat, your choice was to take a chance and stand in a long queue or resort to

baksheesh

(i.e., a bribe disguised as a gift). It was no different for a bag of cement. God forbid, if you should have to travel abroad, a many-hours-long queue and unfriendly customs officials would await you upon return. As an entrepreneur, if you wanted an investment or import license or to stop your competitor from getting one, bribing a senior official in the relevant ministry would do.

It was the reforms, initially carried out on an ad hoc basis but made more systemic in 1991, that freed the ordinary citizens and entrepreneurs from their daily travails and humiliations at the hands of the petty government officials. This may not be obvious to the young, who probably do not even know what the license-permit raj was, but those of us who lived through this history know that the reforms bid good-bye to many forms of corruption.

The critical question, then, is: Why have we witnessed so many mega-corruption cases recently? The success of reforms has opened up new opportunities in several areas to make profits. But because the reforms still have not been extended to these new areas, new avenues for corruption of the older variety have now multiplied.

Thus, reforms (which include opening up access to the world markets) and the growth resulting from them have pushed up the prices of scarce resources, such as minerals and land. These price increases have multiplied the scope for government officials (and colluding businessmen) to make vast sums of illegal money through the pre-reform-type arbitrary and opaque allocations of the rights to extract minerals and to acquire and re-sell land.

The 2G-spectrum scam offers a dramatic example of how the success of past reforms (in opening up new opportunities to make profits) and the failure to extend them (to cover these new opportunities) have combined to produce a mega scandal.

8

With the telephone arriving in India in the early 1880s, it took the country 110 years to reach 5 million phones in 1990â1991. But the spectacular success of telecom reforms brought the number to 300 million at the end of 2007â2008, with the rate of expansion reaching 6.25 million per month. This success turned the spectrum on which cell calls travel into a resource worth tens of billions of dollars. That allegedly allowed telecom minister A. Raja to make handsome sums for himself and his friends when allocating the spectrum to his wealthy friends for a small “fee.” Had reforms been extended to government procurement and sales policies, Raja would not have had the freedom to allocate the spectrum at a prespecified low price to his friends, with bribes allegedly provided in return.

Therefore, the most effective course of action available to the government to curb corruption is clearly the deepening and the broadening of the reforms to new areas. The reform of the antiquated Land Acquisition Act of 1894, the issuance of land titles that would improve access to credit,

9

transparency in government procurement, and competitive auctions of mineral rights and the telecom spectrum are among such measures.

.

Of course, the growth strategy was designed precisely to lift the poor and the underprivileged out of poverty. And as we have demonstrated, the strategy did work and helped the poor and the underprivileged once the counterproductive policy framework began to be dismantled and finally growth materialized. So it is astonishing that any serious analyst would claim that we “crowd out” discussion of poverty.

Yet, Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen (1995) have argued:

Debates on such questions as the details of tax concessions to multinationals, or whether Indians should drink Coca Cola, or whether the private sector should be allowed to operate city buses, tend to “crowd out” the time that is left to discuss the abysmal situation of basic education and elementary health care, or the persistence of debilitating social inequalities, or other issues that have a crucial bearing on the well-being and freedom of the population. (p. vii)

In reviewing this book, Bhagwati (1998) responded sharply:

Much is wrong here. No one can seriously argue that there is a crowding out when the articulation of Indians is manifest in multiplying newspapers, magazines and books and the expression of a whole spectrum of views on economics and politics; this reviewer has noticed no particular shyness in discussing social issues, including inequality and poverty in India. . . . But, more important, the put-down of attention to multinationals misses the point that India's economic reforms require precisely that India join the Global Age and that India's inward direct investments were ridiculously small in 1991, around $100 million, and that this was an important deficiency that had to be fixed.