Chinese For Dummies (15 page)

Read Chinese For Dummies Online

Authors: Wendy Abraham

Table 3-1 Typical Classifiers for Natural Objects

Classifier | Pronunciation | Use |

duÇ | dwaw | flowers |

kÄ | kuh | trees |

lì | lee | grain (of rice, sand, and so on) |

zhī | jir | animals, insects, birds |

zuò | dzwaw | hills, mountains |

Whenever you have a pair of anything, you can use the classifier

shuÄng

å

(

é

) (shwahng). That goes for

yì shuÄng kuà izi

ä¸åç·å

(

ä¸éç·å

) (ee shwahng kwye-dzuh) (

a pair of chopsticks

) as well as for

yì shuÄng shÇu

ä¸åæ

(

ä¸éæ

) (ee shwahng show) (

a pair of hands

). Sometimes a pair is indicated by the classifier

duì

对

(

å°

) (dway), as in

yà duì Ärhuán

ä¸å¯¹è³ç¯

(

ä¸å°è³ç°

) (ee dway are-hwahn) (

a pair of earrings

).

Singular and plural: It's a non-issue

Chinese makes no distinction between singular and plural. If you say the word

shū

书

(

æ¸

) (shoo), it can mean

book

just as easily as

books.

The only way you know whether it's singular or plural is if a number followed by a classifier precedes the word

shū,

as in

WÇ yÇu sÄn bÄn shÅ«.

ææä¸æ¬ä¹¦

. (

ææä¸æ¬æ¸

.) (waw yo sahn bun shoo.) (

I have three books.

).

One way to indicate plurality after personal pronouns

One way to indicate plurality after personal pronouns

wÇ

æ

(waw) (

I

),

nÇ

ä½

(nee) (

you

), and

tÄ

ä»

/

她

/

å®

(tah) (

he/she/it

) and human nouns such as

háizi

å©å

(hi-dzuh) (

child

) and

xuéshÄng

å¦ç

(

å¸ç

) (shweh-shuhng) (

student

) is by adding the suffix

-men

们

(

å

) (men). It acts as the equivalent of adding an

s

to nouns in English.

So many Chinese words are pronounced largely the same way (although each with different tones) that the only way to truly know the meaning of the word is by looking at the character. For example, the third person singular is pronounced “tah” regardless of whether it means

So many Chinese words are pronounced largely the same way (although each with different tones) that the only way to truly know the meaning of the word is by looking at the character. For example, the third person singular is pronounced “tah” regardless of whether it means

he, she,

or

it,

but each one is written with a different Chinese character.

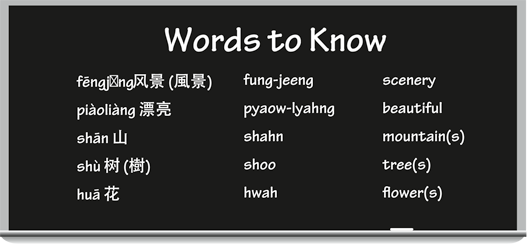

Talkin' the Talk

Susan and Michael are looking at a beautiful field.

Susan:

Zhèr de fÄngjÇng zhÄn pià olià ng!

jar duh fung-jeeng juhn pyaow-lyahng.

This scenery is really beautiful!

Michael:

NÇ kà n! Nà zuò shÄn yÇu nà mme duÅ shù, nà mme duÅ huÄ.

nee kahn! nah dzwaw shahn yo nummuh dwaw shoo, nummuh dwaw hwah.

Look! That mountain has so many trees and flowers.

Susan:

Duì le. Nèi kÄ shù tèbié pià olià ng. Zhè duÇ huÄ yÄ hÄn yÇu tèsè.

dway luh. nay kuh shoo tuh-byeh pyaow-lyahng. jay dwaw hwah yeah hun yo tuh-suh.

You're right. That tree is particularly beautiful. And this flower is also really unique.

Michael:

Nà kÄ shù shà ng yÄ yÇu sÄn zhÄ« niÇo.

nah kuh shoo shahng yeah yo sahn jir nyaow.

That tree also has three birds in it.

If a number and a measure word already appear in front of a pronoun or human noun, such as

If a number and a measure word already appear in front of a pronoun or human noun, such as

sÄnge háizi

ä¸ä¸ªå©å

(

ä¸åå©å

) (sahn-guh hi-dzuh) (

three children

), don't add the suffix

-men

after

háizi

because plurality is already understood.

Never attach the suffix

Never attach the suffix

-men

to anything not human. People will think you're nuts if you start referring to your two pet cats as

wÇde

xiÇo mÄomen

æçå°ç«ä»¬

(

æçå°è²å

) (waw-duh shyaow maow-mun). Just say

WÇde xiÇo mÄo hÄn hÇo, xièxiè.

æçå°ç«å¾å¥½

,

谢谢

. (

æçå°è²å¾å¥½

,

è¬è¬

.) (waw-duh shyaow maow hun how, shyeh-shyeh.) (

My cats are fine, thank you

.), and that should do the trick.

Definite versus indefinite articles

If you're looking for those little words in Chinese you can't seem to do without in English, such as

a, an,

and

the

â articles, as grammarians call them â you'll find they simply don't exist in Chinese. The only way you can tell if something is being referred to specifically (hence, considered definite) or just generally (and therefore indefinite) is by the word order. Nouns that refer specifically to something are usually found at the beginning of the sentence, before the verb:

Háizimen xÇhuÄn tÄ.

å©å们å欢她

. (

å©åååæ¡å¥¹

.) (hi-dzuh-mun she-hwahn tah.) (

The children like her.

)

Pánzi zà i zhuÅzishà ng.

çåå¨æ¡åä¸

. (

ç¤åå¨æ¡åä¸

.) (pahn-dzuh dzye jwaw-dzuh-shahng.) (

There's a plate on the table.

)

Shū zà i nà r.

书å¨é£å¿

. (

æ¸å¨é£å

.) (shoo dzye nar.) (

The book[s] are there.

)

Nouns that refer to something more general (and are therefore indefinite) can more often be found at the end of the sentence, after the verb:

NÇr yÇu huÄ?

åªå¿æè±

? (

åªå

æè±

?) (nar yo hwah?) (

Where are some flowers?/Where is there a flower?

)

NÃ r yÇu huÄ.

é£å¿æè±

. (

é£å

æè±

.) (nar yo hwah.) (

There are some flowers over there./There's a flower over there.

)

Zhèige yÇu wèntÃ.

è¿ä¸ªæé®é¢

. (

éåæåé¡

.) (jay-guh yo one-tee.) (

There's a problem with this./There are some problems with this.

)

These rules have some exceptions: If you find a noun at the beginning of a sentence, it may actually refer to something indefinite if the sentence makes a general comment (instead of telling a whole story), like when you see the verb

These rules have some exceptions: If you find a noun at the beginning of a sentence, it may actually refer to something indefinite if the sentence makes a general comment (instead of telling a whole story), like when you see the verb

shì

æ¯

(shir) (

to be

) as part of the comment:

XióngmÄo shì dòngwù.

çç«æ¯å¨ç©

. (

çè²æ¯åç©

.) (shyoong-maow shir doong-woo.) (

Pandas are animals.

)

Same thing goes if an adjective comes after the noun, such as

Pútáo hÄn tián.

è¡èå¾ç

. (poo-taow hun tyan.) (

Grapes are very sweet.

)

Or if there's an auxiliary verb, such as

XiÇo mÄo huì zhuÄ lÇoshÇ.

å°è²ä¼æèé¼

. (

å°è²ææèé¼

.)

(shyaow maow hway jwah laow-shoo.) (

Kittens can catch mice.

)