Cyclopedia (17 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

Whereas amphetamines act in the short term on a cyclist's nervous system, anabolic agents alter the body's physical state in the medium term, increasing muscle mass and in theory assisting recovery after training. Given that cyclists don't want muscle mass, their use may often be counterproductive. Gradually the testers caught up with these, although the male hormone testosterone was still being used into the 21st century, according to the Scot David Millar.

Avoiding drug-tests

was something of an art, according to the SOIGNEUR Willy Voet, the lead protagonist in the Festina scandal of 1998. Initially, riders simply didn't show up, but after JACQUES ANQUETIL's hour record was refused in 1968 because he didn't give a sample, that stopped. The most famous case of attempted evasion was that of the Tour de France leader Michel Pollentier, shopped in 1978 (see page 114). Voet describes how a rider would stick a condom filled with clean urine up his anus and how urine samples might be switched by distracting the tester. More recently, it's said that the EPO test can be avoided by urinating over fingers that have been dipped in laundry detergent.

was something of an art, according to the SOIGNEUR Willy Voet, the lead protagonist in the Festina scandal of 1998. Initially, riders simply didn't show up, but after JACQUES ANQUETIL's hour record was refused in 1968 because he didn't give a sample, that stopped. The most famous case of attempted evasion was that of the Tour de France leader Michel Pollentier, shopped in 1978 (see page 114). Voet describes how a rider would stick a condom filled with clean urine up his anus and how urine samples might be switched by distracting the tester. More recently, it's said that the EPO test can be avoided by urinating over fingers that have been dipped in laundry detergent.

“Not me, guv”âthe best excuses for doping/possession from cyclists

=

Â

Franck Vandenbroucke

: “The steroids and EPO were for my dog.”

: “The steroids and EPO were for my dog.”

Â

Raimondas Rumsas

: “The 40 diffferent drugs in the back of my wife's car were for my mother-in-law.”

: “The 40 diffferent drugs in the back of my wife's car were for my mother-in-law.”

Â

Tyler Hamilton

: “I was one of twins, one of which died in the womb, that's why I had two different types of blood.”

: “I was one of twins, one of which died in the womb, that's why I had two different types of blood.”

Â

Ivan Basso

: “I had blood removed and saved for reinjection but it was âjust in case' and I never used it.”

: “I had blood removed and saved for reinjection but it was âjust in case' and I never used it.”

Â

Floyd Landis

: “I got drunk after a bad day in the mountains, hence my high testosterone levels.”

: “I got drunk after a bad day in the mountains, hence my high testosterone levels.”

Â

Richard Virenque

: “I had no idea what I was being given. If I was given drugs it was without my knowledge.”

: “I had no idea what I was being given. If I was given drugs it was without my knowledge.”

Belgian mix

was a cocktail of drugs that might include heroin, morphine, amphetamine, and cocaine. It was used mainly for training in bad weather, for partying, and to help stay awake while driving between races. It was either sold by dealers or produced by a group of cyclists who would all put a different drug in the pot; as a result, its effects would vary depending on which drug was there in the greatest quantity.

was a cocktail of drugs that might include heroin, morphine, amphetamine, and cocaine. It was used mainly for training in bad weather, for partying, and to help stay awake while driving between races. It was either sold by dealers or produced by a group of cyclists who would all put a different drug in the pot; as a result, its effects would vary depending on which drug was there in the greatest quantity.

Blood boosters

became popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The first and most popular was erythropoietin, or EPO, a synthetic version of the hormone that stimulates the body to produce more red blood cells, thus increasing its capacity to supply oxygen to the muscles; this in turn enabled more power to be produced. This was a variant on

blood doping

, used in the 1970s and early 1980s, where blood would be removed from an athlete and reinjected just before competition. That eventually evolved into using someone else's blood, leading to rumors that some teams hired staff according to their blood group. After the introduction of an EPO test in 2000, the practice came back into vogue, along with sophisticated EPO variants such as CERA.

became popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The first and most popular was erythropoietin, or EPO, a synthetic version of the hormone that stimulates the body to produce more red blood cells, thus increasing its capacity to supply oxygen to the muscles; this in turn enabled more power to be produced. This was a variant on

blood doping

, used in the 1970s and early 1980s, where blood would be removed from an athlete and reinjected just before competition. That eventually evolved into using someone else's blood, leading to rumors that some teams hired staff according to their blood group. After the introduction of an EPO test in 2000, the practice came back into vogue, along with sophisticated EPO variants such as CERA.

Blood tests

were introduced by the UCI in 1997 and have become more and more sophisticated over the years. Initially they were intended to limit EPO use, but now they are used more to discover cyclists who are suspectâthese are put on the UCI's red list and they are then targeted for testing. In 2009 the UCI brought in the

blood passport

system, which draws up a detailed picture of each pro rider's blood parameters; anomalies can result in a ban or in highly targeted testing.

were introduced by the UCI in 1997 and have become more and more sophisticated over the years. Initially they were intended to limit EPO use, but now they are used more to discover cyclists who are suspectâthese are put on the UCI's red list and they are then targeted for testing. In 2009 the UCI brought in the

blood passport

system, which draws up a detailed picture of each pro rider's blood parameters; anomalies can result in a ban or in highly targeted testing.

Cortisone

, the painkiller the body produces during exercise, was frequently injected in artificial form during the 1980s and 1990s for its euphoric effects, but can now be detected.

, the painkiller the body produces during exercise, was frequently injected in artificial form during the 1980s and 1990s for its euphoric effects, but can now be detected.

Insulin

was found occasionally at races in the early 21st century and was assumed to be used to speed up sugar

intake to aid recovery after tough stages.

was found occasionally at races in the early 21st century and was assumed to be used to speed up sugar

intake to aid recovery after tough stages.

Legal Drugs

have also been commonly used, most notably caffeine, which was once banned above a certain limit but is now permitted. Most riders drink coffee before a race, and Coke or Red Bull in the final phase, but suppositories and tablets are also used.

have also been commonly used, most notably caffeine, which was once banned above a certain limit but is now permitted. Most riders drink coffee before a race, and Coke or Red Bull in the final phase, but suppositories and tablets are also used.

Out-of-competition testing

is carried out all year round, with cyclists declaring their whereabouts for set periods each week.

is carried out all year round, with cyclists declaring their whereabouts for set periods each week.

Painkillers

were popular in cycling's early days, with morphine and heroin used in the late 19th century to help riders complete six-day races. They were also taken in the 1950s as part of the Anquetil cocktail: analgesic to take away pain in the legs, amphetamine to counter the drowsiness these induced, sleeping pills to bring the rider down at night.

were popular in cycling's early days, with morphine and heroin used in the late 19th century to help riders complete six-day races. They were also taken in the 1950s as part of the Anquetil cocktail: analgesic to take away pain in the legs, amphetamine to counter the drowsiness these induced, sleeping pills to bring the rider down at night.

Police raids

on races in search of banned substances became more common after the Festina scandal of 1998. The Italian police were the most enthusiastic, but the country's slow-moving legal system meant convictions were rare; French customs men also became active, most notably in 2002, with the detention of Edita Rumsas, the wife of Raimondas, who finished third in the Tour. Her car was crammed with drugs.

on races in search of banned substances became more common after the Festina scandal of 1998. The Italian police were the most enthusiastic, but the country's slow-moving legal system meant convictions were rare; French customs men also became active, most notably in 2002, with the detention of Edita Rumsas, the wife of Raimondas, who finished third in the Tour. Her car was crammed with drugs.

Recreational drugs

are not commonly found in cycling, although there is evidence of a cocaine problem. The 1998 Tour winner MARCO PANTANI died of a cocaine overdose, as did the top Spanish climber Jose-Maria Jimenez, while the Belgian champion Tom Boonen was found to have taken the drug on two occasions.

are not commonly found in cycling, although there is evidence of a cocaine problem. The 1998 Tour winner MARCO PANTANI died of a cocaine overdose, as did the top Spanish climber Jose-Maria Jimenez, while the Belgian champion Tom Boonen was found to have taken the drug on two occasions.

Sleeping pills

have been used for recreational purposes (the Cofidis scandal of 2004 involving Millar revealed this) but were also used to counter all that caffeine, and, in the past, other uppers. As one Tour rider said, “You can tell which week of the Tour you are in by the number of sleepers you take: one in the first week, two in the second, three in the third.”

have been used for recreational purposes (the Cofidis scandal of 2004 involving Millar revealed this) but were also used to counter all that caffeine, and, in the past, other uppers. As one Tour rider said, “You can tell which week of the Tour you are in by the number of sleepers you take: one in the first week, two in the second, three in the third.”

DRUGS; SLANG

One illustration of the depth of doping culture in cycling is the fact that French, cycling's lingua franca, has an almost endless repertoire of slang referring to drug use. Some selected highlights:

| PHRASE | ENGLISH MEANING | ACTUAL MEANING |

|---|---|---|

| Charger la chaudière | Warm up the heater | Use amphetamines |

| Allumer les phares | Put on the headlights | Use amphetamines |

| Saler la moutarde | Salt the mustard | General use of drugs |

| Pisser violet | Piss violet | General use of drugs |

| Avoir la valise magique | Have a magic suitcase | General use of drugs |

| Diner chez Virenque | Dine with Virenque | Use drugs (refers to the Festina drug scandal of 1998) |

| La flèche | Arrow | Needle or adapted syringe |

| Tonton, tintin, fifi | Various kinds of amphetamine. | |

| La topette | Small bottle with a stimulant | English racing slang refers to this as a “charge bottle” |

| Spain has the following: | ||

| Marker pen = cortisone | ||

| Oil change = blood transfusion | ||

| Pelas (slang for pesetas) = units of EPO |

E

EASTERN EUROPE

Sports were an important way in which the communist nations of Eastern Europe asserted themselves during the Cold War, and cycling was one of the key disciplines. The value of international victories as propagandaâat home as evidence of the system's power, abroad to show it could compete on equal termsâhad been rapidly appreciated, and entire sports infrastructures were built, with the finest talent creamed off into academies based in the biggest cities: most legendary was the Russian pursuit school in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) run by the hyper-tough Alexandr Kuznetsov.

Sports were an important way in which the communist nations of Eastern Europe asserted themselves during the Cold War, and cycling was one of the key disciplines. The value of international victories as propagandaâat home as evidence of the system's power, abroad to show it could compete on equal termsâhad been rapidly appreciated, and entire sports infrastructures were built, with the finest talent creamed off into academies based in the biggest cities: most legendary was the Russian pursuit school in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) run by the hyper-tough Alexandr Kuznetsov.

Training regimes were draconian, the demands on personal life and health were considerable, but the rewards were tangible: privileges, apartments, cars, and, above all, foreign travel and the chance to earn hard currency. Cycles produced in Eastern Europe were often crude and poorly made, however, so the Soviet team rode Italian bikes made by Ernesto Colnago. The clubs tended to get the hand-me-downs. Western gear of any kind had high black-market value into the early 1990s, as did Western cycling magazines and posters.

By the 1970s Poland, the Soviet Union, and East Germany all boasted “amateur” cycling teams that were not far off the standard of pro squads in Western Europe, with full-time cyclists whose “jobs” were often military. The East Europeans were almost unbeatable in their own events. The biggest of these was the BerlinâWarsawâPrague Peace Race, founded in 1948

and sponsored by newspapers in East Germany, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. A blue jersey with a white dove on the front was worn by the leading team, and in its heyday the route covered 2,000 km in front of crowds numbering in the millions.

and sponsored by newspapers in East Germany, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. A blue jersey with a white dove on the front was worn by the leading team, and in its heyday the route covered 2,000 km in front of crowds numbering in the millions.

East-bloc racers were just as fearsome abroad, dominating major amateur events and walking off with many of the medals in world track and road championships. “We were like amateurs against pros,” said Bob Downs, a British cyclist who was one of the elite few who had the legs to put up a decent fight against the Russians and Poles in the MILK RACE in the 1970s. “The whole Russian team used to get on the front and not let anyone else in. The only way you could stand a chance was to ride as near as possible to them and wait for them to make a mistake.”

“Every time an East German climbed on to the rostrum, win or lose, there was the same unsmiling solemn glare. There is no getting away from it, [they] are consistently phenomenal, technically brilliant athletes,” wrote Les Woodland in the 1981

International Cycling Guide

. The East Europeans were often impenetrable for the media but had a love of shopping, selling anything they couldâmost often tubular tiresâto get currency.

International Cycling Guide

. The East Europeans were often impenetrable for the media but had a love of shopping, selling anything they couldâmost often tubular tiresâto get currency.

The system was comprehensive and sophisticated, recalls the former East German trainer Heiko Salzwedel. At the bottom of the pyramid was a network of sports clubs attached to major enterprises such as the police or railways. At the top were the half-dozen national cycling centers across East Germany, each with about 10 trainers, dealing with up to 100 athletes. Children were selected from an early age, partly through biometric tests that assessed their capacity for various sports, partly through their parents' background, partly through selection races.

There were official guidelines, but coaches had a fair degree of flexibility in setting their own criteria; riders' Stasi

files would be checkedâto see whether a potential athlete had West German connections, for exampleâbut coaches might push better athletes with undesirable backgrounds higher up selection lists to ensure they got in the team anyway. The screening systems were later adapted for use by the cycling teams of Australia and GREAT BRITAIN.

files would be checkedâto see whether a potential athlete had West German connections, for exampleâbut coaches might push better athletes with undesirable backgrounds higher up selection lists to ensure they got in the team anyway. The screening systems were later adapted for use by the cycling teams of Australia and GREAT BRITAIN.

The sudden collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 left the sports centers across Eastern Europe short of money, and a vast number of talented amateurs came on the market: they flooded into cycling. The sprinter DJAMOLIDIN ABDUZHAPAROV made the biggest impact alongside Olaf Ludwig, Andrei Tchmil, and Zenon Jaskuta, who in 1993 was the first Pole to make it to the Tour podium. Jan Ullrich was the first product of the Eastern system to win the Tour in 1997.

The legacy of the old Eastern Europe is obvious now. Individual nations from the former Soviet Union such as Ukraine and Belarus punch above their weight on the international stage, while almost every professional cycling team in the world has at least one “Goombah.”

This term was coined by LANCE ARMSTRONG's biographer Dan Coyle, who wrote that Viatcheslav Ekimov, Alexandr Vinokourov, and Jens Voigt “had been selected as children, their growth plates and femurs measured against that of a âsuperior child' and [had been] whisked away to ... sports schools throughout the former Soviet empire. Once there their life became an endless series of training exercises, the governing philosophy of which was summed up by a former coach: âyou throw a carton of eggs against the wall, then keep the ones that do not break.'”

Six Great Unbreakable Eggs

=

Â

Olaf Ludwig

: Ludwig's sprint win in Besançon in the 1990 Tour de France was the first and last for East Germany, as unification came not long afterwards. Prior to that the rider from Gera had won the Olympic road race in 1988, two overall victories in the Peace Race and a record 38 stages, and two East German Sportsman of the Year awards. As a pro he landed the World Cup in 1992, the green jersey in the 1990 Tour, and the Amstel Gold Race.

: Ludwig's sprint win in Besançon in the 1990 Tour de France was the first and last for East Germany, as unification came not long afterwards. Prior to that the rider from Gera had won the Olympic road race in 1988, two overall victories in the Peace Race and a record 38 stages, and two East German Sportsman of the Year awards. As a pro he landed the World Cup in 1992, the green jersey in the 1990 Tour, and the Amstel Gold Race.

Â

Sergei Soukhouroutchenkov

: 1980 Moscow Olympic games road race winner, dominant in amateur racing from 1979 to 1981, with two wins in the Tour de l'Avenir, two in the Giro delle Regioni, and one in the Peace Race. Turned pro briefly in 1989â90 but by then his best days were gone.

: 1980 Moscow Olympic games road race winner, dominant in amateur racing from 1979 to 1981, with two wins in the Tour de l'Avenir, two in the Giro delle Regioni, and one in the Peace Race. Turned pro briefly in 1989â90 but by then his best days were gone.

Â

Gustave-Adolf “Täve” Schur

: East German double world amateur champion (1958â9), gave up his chance of a third title by helping his friend Bernhard Eckstein. He was also a double Peace Race winner (1955 and 1959). He later became a parliamentiary deputy; his son Jan rode briefly as a professional in the early 1990s. His 1955 biography sold 100,000 copies, such was his popularity.

: East German double world amateur champion (1958â9), gave up his chance of a third title by helping his friend Bernhard Eckstein. He was also a double Peace Race winner (1955 and 1959). He later became a parliamentiary deputy; his son Jan rode briefly as a professional in the early 1990s. His 1955 biography sold 100,000 copies, such was his popularity.

Â

Viktor Kapitonov

: Russian who won the Olympic road race in Rome in 1960, sprinting twiceâwith a lap to go because he misread the lapboard, then for real a lap later. He became national trainer, masterminding all those dollar-winning trips to the west in the 1970s.

: Russian who won the Olympic road race in Rome in 1960, sprinting twiceâwith a lap to go because he misread the lapboard, then for real a lap later. He became national trainer, masterminding all those dollar-winning trips to the west in the 1970s.

Â

Viatcheslav Ekimov

: Took four world pursuit titles (three as an amateur, one as a pro), and two Olympic gold medals, the first in the team pursuit in 1988, the second in the time trial in 2000. He was the finest product of the Kuznetsov cycling school. “Eki” went on to ride and finish 15 Tours de France. He was a key

domestique

to Lance Armstrong and went on to work with the Texan at the RadioShack team.

: Took four world pursuit titles (three as an amateur, one as a pro), and two Olympic gold medals, the first in the team pursuit in 1988, the second in the time trial in 2000. He was the finest product of the Kuznetsov cycling school. “Eki” went on to ride and finish 15 Tours de France. He was a key

domestique

to Lance Armstrong and went on to work with the Texan at the RadioShack team.

Â

Andrei Tchmil

: Turned pro with the first batch of Russians in 1989, and went on to take victories in PARISâROUBAIX (1994), ParisâTours (1997), MILANâSAN REMO (1999), and the Tour of FLANDERS (2000). He changed nationality several times, riding for Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, and Belgium, and went on to be minister of sport in his native Moldova before founding the Katyusha pro team.

: Turned pro with the first batch of Russians in 1989, and went on to take victories in PARISâROUBAIX (1994), ParisâTours (1997), MILANâSAN REMO (1999), and the Tour of FLANDERS (2000). He changed nationality several times, riding for Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, and Belgium, and went on to be minister of sport in his native Moldova before founding the Katyusha pro team.

END TO END

The 850-plus miles from Land's End to John O'Groatsâfrom one end of Great Britain to the otherâis one of the most evocative long-distance rides, tackled for charity or simply for the sense of achievement it engenders. It is also the most prestigious British long-distance record. Most End-to-Enders start in Cornwall, to take advantage of the prevailing southwesterly winds. The toughest sections are early on, over the constantly climbing roads of Cornwall and Devon, and in the final quarter through the Scotttish highlands.

The 850-plus miles from Land's End to John O'Groatsâfrom one end of Great Britain to the otherâis one of the most evocative long-distance rides, tackled for charity or simply for the sense of achievement it engenders. It is also the most prestigious British long-distance record. Most End-to-Enders start in Cornwall, to take advantage of the prevailing southwesterly winds. The toughest sections are early on, over the constantly climbing roads of Cornwall and Devon, and in the final quarter through the Scotttish highlands.

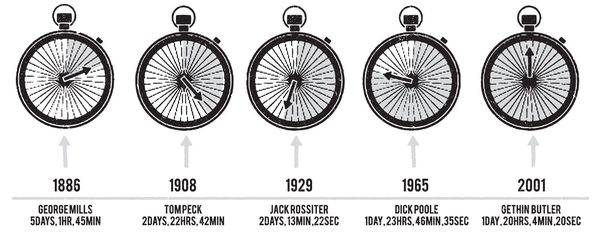

The first End-to-Enders were H. Blackwell and C. A. Harmon of the Canonbury Bicycle Club who did it on old ordinaries in 1880, taking 13 days. The first name on the Road Record Association record sheets is G. P. Millsâalso a winner of the BordeauxâParis Classicâwith a time of 5 days, 1 hour, 45 minutes, on a penny farthing with a 52-inch front wheel. Mills was paced by other cyclists, as was customary in those days; the first unpaced record was set in 1903 by C. J. Mather, in 5 days, 5 hours, 12 minutes.

The first man to achieve the distance inside two days was Dick Poole, in 1965. Poole then went on to attempt the 1,000-mile record; frustratingly, he covered 1,010 miles (enough to allow for error, so his timekeeper thought) but was still found to be a few yards short so the record was not ratified. Attempts on the record have led to extreme feats of endurance, partly because the only way to break it is to go without sleep as far as possible, but also because the wind can change over the 48 hours from a helpful southerly to a northerly headwind. In 1980 the Viking Cycles professional Paul Carbutt benefited from the opening of the Forth Bridge which cut 13 miles off the distance to break Poole's record but collapsed due to heatstroke southwest of Edinburgh. He was unconscious for about 25 minutes but was put back on his bike to continue with a damp facecloth under his racing hat.

The record set by Andy Wilkinson using the highly aerodynamic Windcheetah RECUMBENT was unofficial but was as extreme as any of the others. Because of the temperatures building up inside the enclosed bike, Wilkinson needed about two liters of fluid an hour to avoid dehydration, so it took a 20-strong support team to give him a bottle every half-hour, collect discarded bottles, and then overtake him to hand up new ones. His fluid output was also high: “We rigged up a special condom connected to a metre-long tube to provide relief without having to stop. The tube exited the Windcheetah at the back of the fairing,” says the Windcheetah website. Wilkinson reached close to 80 mph on long descents, and covered the distance in 41 hours, 4 minutes, 22 seconds including a stop of almostan hour to replace a rear axle.

Dick Poole's End-to-End Eats

=

Between Land's End and John O'Groats in 1965 Poole got through 2 pounds of fruitcake, 11 packets of malt loaf, a gallon of rice and fruit salad, 7 pints of Complan, 12 oranges, 8 pints of coffee, 13 pints of tea, and 8 pints of Ribena.

ENVIRONMENT

Cycling is now a recognized means of lowering one's carbon footprint. The figures speak for themselvesâ100 calories takes a cyclist 3 miles, a car all of 280 feet. In 2009 research indicated that if cycling use in cities doubles from 4 percent of journeys to 8 percent, there would be a total drop of 1.1 percent in carbon emissions. If those journeys are intermodal (public transport + bike), the figure can go up to 1.8 percent because greater distances can be covered.

Cycling is now a recognized means of lowering one's carbon footprint. The figures speak for themselvesâ100 calories takes a cyclist 3 miles, a car all of 280 feet. In 2009 research indicated that if cycling use in cities doubles from 4 percent of journeys to 8 percent, there would be a total drop of 1.1 percent in carbon emissions. If those journeys are intermodal (public transport + bike), the figure can go up to 1.8 percent because greater distances can be covered.

On the other hand, cycling as a pastime rather than a means of transport is by no means carbon friendly. Driving from London to the south of France with a bike on the roofrack creates 360 kgm of CO

2

; taking the train and hiring a bike creates 100 kgm; flying with the bike in the hold creates 850 kgm, more than heating the average house for a year.

2

; taking the train and hiring a bike creates 100 kgm; flying with the bike in the hold creates 850 kgm, more than heating the average house for a year.

Few studies exist into the carbon footprint of bike races but the number of vehicle miles involved suggest that it is horrendous. That is borne out by a study from the International Institute for Sport Science and Technology, which calculated that the Tour of Romandie, a six-day stage race for pros, produced 138 tons of CO

2

, which is just under the amount of CO

2

emissions produced by Nauru, an island state in the South Pacific.

2

, which is just under the amount of CO

2

emissions produced by Nauru, an island state in the South Pacific.

Other books

09-Twelve Mile Limit by Randy Wayne White

Mr. Murder by Dean Koontz

White Shadows by Susan Edwards

Kiss Me When the Sun Goes Down by Lisa Olsen

White Light by Alex Marks

Steam Train, Dream Train by Sherri Duskey Rinker, Tom Lichtenheld

Carolyn Davidson by The Forever Man

Predator and Prey Prowlers 3 by Christopher Golden

The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs by Elaine Sciolino

Siren's Serenade (The Wiccan Haus) by Dominique Eastwick