Cyclopedia (19 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

FISHER, Gary

(b. 1950)

(b. 1950)

Together with his college roommate Charlie Kelly and frame-builder Tom Ritchey, Fisher is considered one of the founding fathers of MOUNTAIN-BIKING. Fisher was a CYCLO-CROSS rider, initially a road racer, but was suspended for a time because officials considered that his hair was too long.

By the mid-1970s he had begun modifying a 1930s SCHWINN Excelsior X bike for off-road use, fitting salvaged drum-brakes, motorcycle brake levers, and triple chainrings. Such “clunkers” were the prototype for today's mountain bikes.

Fisher was one of the participants in the REPACK downhill race run by Kelly, who began using the term “mountain bike” in 1979 to describe the fat-tired, multi-geared, andâin those daysâextremely heavy bikes the Repack crew were using: in that year he and Fisher founded MountainBikes, the first company to make the off-road bikes. Ritchey was their framebuilder and later founded his own brand, an industry-leader to this day.

The first year's production was just 160 bikes, retailing at $1,300 each. With no cashflow

Fisher, Kelly, and Ritchie relied on trusting customers to pay up front. MountainBikes ceased trading in 1983, and Fisher then formed his own company, which is now owned by Trek and still makes bikes bearing his name.

Fisher, Kelly, and Ritchie relied on trusting customers to pay up front. MountainBikes ceased trading in 1983, and Fisher then formed his own company, which is now owned by Trek and still makes bikes bearing his name.

FIXED-WHEEL

Curiously, even as cycle component makers pushed the number of gears available on most road-racing bikes into the 20s and 30s, London and some other major cities worldwide were hit by a new craze: fixed-gear bikes that were based on the stripped-down models used by cycle COURIERS and by HILL CLIMB specialists.

Curiously, even as cycle component makers pushed the number of gears available on most road-racing bikes into the 20s and 30s, London and some other major cities worldwide were hit by a new craze: fixed-gear bikes that were based on the stripped-down models used by cycle COURIERS and by HILL CLIMB specialists.

Top London shop Condor Cycles, which produced the first new-era “fixie” in 2002, estimated that it had sold several thousand of the bikes in their first seven years. Relatively few were visible on the streets, implying that they were retained for weekend use or simply to be admired.

Fixie adherents were happy to crunch up hills in an over-large gear and rev out downhill, because the machines were stylish and minimalist. They were also retroâhinting at the halcyon club cycling days between the 1920s and the 1950s when virtually every clubman would turn out on fixed for racing and social rides.

“The bike is a blank canvas on which riders express an individuality or a community ... an aesthetic reference point shared with designers and artists who have helped shape fashion and street culture,” said the intro to

Fixed

, a glossy book about the bikes.

Fixed

, a glossy book about the bikes.

Â

(SEE

GEARS

FOR HOW BIKES BEGAN TO MOVE BEYOND THE FIXED-WHEEL BACK IN THE 1890S)

GEARS

FOR HOW BIKES BEGAN TO MOVE BEYOND THE FIXED-WHEEL BACK IN THE 1890S)

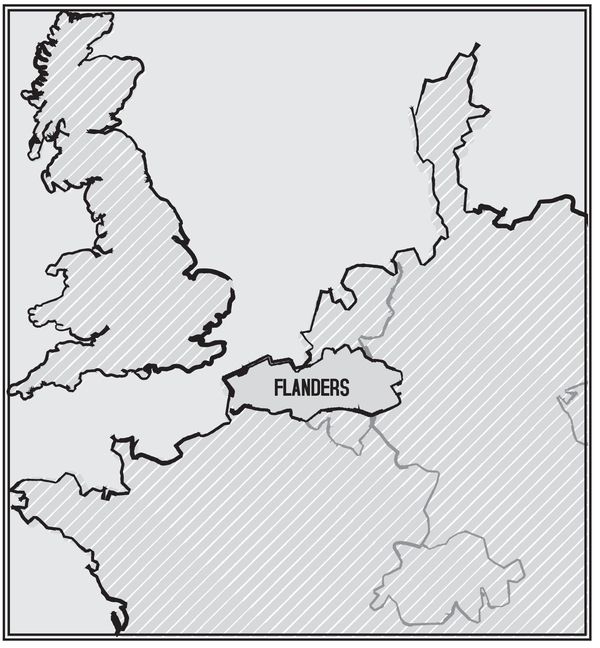

FLANDERS

A small chunk of Europe that has an influence on bike racing out of proportion to its area or population. There are more bike races held in the Flemish-speaking area of Belgium than anywhere else in the world; the local people are simply obsessed with the sport, and above all with “their” CLASSIC, the Tour of Flanders, founded in 1913 and now the climax of a series of gritty races in late March and early April.

A small chunk of Europe that has an influence on bike racing out of proportion to its area or population. There are more bike races held in the Flemish-speaking area of Belgium than anywhere else in the world; the local people are simply obsessed with the sport, and above all with “their” CLASSIC, the Tour of Flanders, founded in 1913 and now the climax of a series of gritty races in late March and early April.

One episode sums up the local mania with cycling and “De Ronde”: in 1984 a farmer who lived on the race route grew jealous of all the attention given to the race's most notorious climb, the Koppenberg, which was situated on his neighbor's fields (see COBBLES for more on this ascent). He announced in the papers that he was going to create his own climb. Within 18 months a strip of cobbles had been laid up his fields: the Patersberg has been part of the race since 1986.

The Koppenberg itself shows the depth of the Flemish obsession. It was removed from the race in 1987, and 10 years later a local paper ran an April Fool's story that it was to be paved over. Two thousand people turned up for a demonstration in support of the climb: as a result it was then restored at a cost of $325,000 using cobbles imported from Poland. The importance of cycling in Belgium was summed up by the presence of the minister of culture at the official reopening.

Situated between the North Sea, the French border, and the French-speaking area of Wallonia to the south, Flanders has been fought over by invading armies for years. Local identity is passionately assertedâthe lion flag is flown by nationalists at most major racesâand it dominates Belgian cycling as south Wales dominates Welsh rugby. The cultural divide between French- and Flemish-speaking areas is strongly felt: neither likes the other much and the cycling rivalry is an assertion of that feeling.

Even within Flanders itself there are local rivalries even down to the papers that run the bike races: the Tour of Flanders, organized by

Het Niewsblad

, was the only classic to be run in occupied Europe during the Second World War, with the Germans helping to police the route. A second newspaper,

Het Volk

, started its own event, also called the Tour of Flanders, on a similar course after liberation, to make the point that its rival had been accused of collaboration. It was later ruled that the name should be changed (see CLASSICS for more on this race and other major one-dayers).

Het Niewsblad

, was the only classic to be run in occupied Europe during the Second World War, with the Germans helping to police the route. A second newspaper,

Het Volk

, started its own event, also called the Tour of Flanders, on a similar course after liberation, to make the point that its rival had been accused of collaboration. It was later ruled that the name should be changed (see CLASSICS for more on this race and other major one-dayers).

The wind and rain and bad roads breed a species of hard men who live to an almost monastic canon of hard work and self-sacrifice. Every village seems to boast a Classic winner, who usually runs a bike shop or café. Flandrian cycling is essentially nostalgic: the heroes of today never quite live up to those of yesteryear. Several cyclists, including the top Classic rider Johan Museeuw, have been dubbed the “last of the Flandrians,” another of whom was the evocatively named Alberic “Brick” Schotte. Schotte was brought out of his first communion to watch the Tour of Flanders go past in 1930 and as an amateur he would get up at 3:30 AM to go to work to ensure that he could start training at 1 PM. He rode the Classic 20 times and was a strong influence on another cycling hardman, the Irishman SEAN KELLY, who spent most of his career based in Belgium.

The Key Flandrian Climbs:

=

Â

Old Kwaremont

: 2.2 km long, 11% steepest, approx 95 km from the finish

: 2.2 km long, 11% steepest, approx 95 km from the finish

Â

Patersberg

: 360 m long, 13% steepest, approx 90 km from finish

: 360 m long, 13% steepest, approx 90 km from finish

Â

Koppenberg

: 600 m long, 25% steepest, approx 85 km from finish*

: 600 m long, 25% steepest, approx 85 km from finish*

Â

Kapelmuur

: 475 m long, 20% steepest, approx 25 km from finish

: 475 m long, 20% steepest, approx 25 km from finish

Â

Bosberg

: 980 m long, 11%steepest, approx 20 km from finish

: 980 m long, 11%steepest, approx 20 km from finish

Â

*not always included in route

Few foreigners break through in Flanders but those who do become adopted sons, such as Kelly and the Italian Fiorenzo Magni, who won the Classic three times in a row from 1949â51. So too the Moldovan Andrei Tchmil, who led Belgian's biggest team, Lotto, for nine years, and was naturalized as Belgian in 2000. Home greats

include RIK VAN LOOY, ROGER DE VLAEMINCK, Museeuwâ10 times a Classic winnerâand Rik Van Steenbergen, a hulking brute known as Rik I so he would not be confused with Van Looy (Rik II). In spite of a legendary Flanders win in 1969, EDDY MERCKX never quite fitted in to this culture because he was a French-speaker from Brussels: his big rivals Walter Godefroot and Freddy Maertens were more popular.

include RIK VAN LOOY, ROGER DE VLAEMINCK, Museeuwâ10 times a Classic winnerâand Rik Van Steenbergen, a hulking brute known as Rik I so he would not be confused with Van Looy (Rik II). In spite of a legendary Flanders win in 1969, EDDY MERCKX never quite fitted in to this culture because he was a French-speaker from Brussels: his big rivals Walter Godefroot and Freddy Maertens were more popular.

What might be called “Tour of Flanders country” is an area of little hills along the Scheldt and Deinze rivers known as the Flemish Ardennes; the race began coming here in the 1950s, when it needed to be made tougher but the roads were generally being improved, so the organizers had to seek out small lanes and steep hills.

The race loops up and down onto the hills, starting with the Old Kwaremont, a windswept stretch of cobbles up a bleak hillside with a café at the top, and culminating with the “Chapel wall”âKapelmuurâat Geraardsbergen, which twists upward at 20 percent to a chapel by a grassy bank where the fans congregate.

FOLDING BIKES

These aim to provide a solution to a perennial bike problem: getting the thing in a small car, putting it in a house or office where space is at a premium, or fitting on a train where the operator doesn't want to carry them. It's not always been that way; an early folder, made by MIKAEL PEDERSEN, was used in the Boer War by the British Army, and in the Second World War British paratroopers used folders made by BSA, which were full-sized bikes that could be carried when jumping out of aircraft.

These aim to provide a solution to a perennial bike problem: getting the thing in a small car, putting it in a house or office where space is at a premium, or fitting on a train where the operator doesn't want to carry them. It's not always been that way; an early folder, made by MIKAEL PEDERSEN, was used in the Boer War by the British Army, and in the Second World War British paratroopers used folders made by BSA, which were full-sized bikes that could be carried when jumping out of aircraft.

Folding bikes compromise on performance: they either hinge at the mid-point of the frame or

have a flip-round rear triangle. They usually have small wheels, and the wheelbase may be shorter than usual, all to save space. Tires may be fatter than usual, and the frame tubes may well be more substantial than on a conventional road bike; however, the aluminium Bickerton, made in the 1970s and 1980s, weighed in at just 18 lb.

have a flip-round rear triangle. They usually have small wheels, and the wheelbase may be shorter than usual, all to save space. Tires may be fatter than usual, and the frame tubes may well be more substantial than on a conventional road bike; however, the aluminium Bickerton, made in the 1970s and 1980s, weighed in at just 18 lb.

Among the best models are those from British company Brompton, whose top of the range bike weighs in at less than 10 kg and has 16-inch wheels and rear suspension. Small wheel bikes made by MOULTON qualify as folders, because they can be “split” for storage or transport. At the radical end of the spectrum, the Strida has drum brakes and a rubber drive belt and futuristic looks. Aficionados also swear by the Pocket Rocket, which fits in a suitcase 22 Ã 29 Ã 10 inches yet turns into a replica racing bike.

Other books

All the Way by Megan Stine

Highland Shadows (Beautiful Darkness Series Book 1) by Baldwin, Lily

Flying the Dragon by Natalie Dias Lorenzi

Reckless Rules (Brambridge Novel 4) by Pearl Darling

Signed, Sealed, Delivered by Sandy James

The Saint and the Happy Highwayman by Leslie Charteris

Private Island: Why Britian Now Belongs to Someone Else by James Meek

Harem by Colin Falconer

Being There by Jerzy Kosinski

Kill Zone (A Spider Shepherd Short Story) by Stephen Leather