Cyclopedia (16 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

The Granfondo Marco Pantani

includes the Gavia and Mortirolo, starting and finishing in the town of Aprica.

includes the Gavia and Mortirolo, starting and finishing in the town of Aprica.

The great Dolomite climbs feature in the RAID Alpine route from Thonon les Bains to Trieste.

DOPING

See DRUGS

See DRUGS

DOUBLE

Cycle racing has two legendary “doubles”: most prestigious is the GIRO D'ITALIA followed by the TOUR DE FRANCE in the same year, a rare feat achieved only by the greats: FAUSTO COPPI (1949 and 1952), JACQUES ANQUETIL (1964), EDDY MERCKX (1970, 1972, 1974), BERNARD HINAULT (1982, 1985), STEPHEN ROCHE (1987), and MARCO PANTANI (1998). MIGUEL INDURAIN of Spain achieved a “double double” by winning Giro and Tour two years running, 1992 and 1993, while in 1974 and 1987 respectively Merckx and Roche achieved a legendary triple: Giro, Tour, and world championships.

Cycle racing has two legendary “doubles”: most prestigious is the GIRO D'ITALIA followed by the TOUR DE FRANCE in the same year, a rare feat achieved only by the greats: FAUSTO COPPI (1949 and 1952), JACQUES ANQUETIL (1964), EDDY MERCKX (1970, 1972, 1974), BERNARD HINAULT (1982, 1985), STEPHEN ROCHE (1987), and MARCO PANTANI (1998). MIGUEL INDURAIN of Spain achieved a “double double” by winning Giro and Tour two years running, 1992 and 1993, while in 1974 and 1987 respectively Merckx and Roche achieved a legendary triple: Giro, Tour, and world championships.

The other “double” is the Ardennes double: victories in Flèche Wallonne and LiègeâBastogneâLiège in the same year (see CLASSICS). Cyclists who have managed this are: Ferdi Kubler (Switzerland) 1951â2; Stan Ockers (Belgium) 1955; Eddy Merckx (Belgium) 1972; Moreno Argentin (Italy) 1991; Davide Rebellin (Italy) 2004; Alejandro Valverde (Spain) 2006.

DOWNHILL

The original form of MOUNTAIN-BIKING, and still the most traditional variant of the sport, with its principles unchanged since the days of the REPACK downhill in California in the late 1970s. It is simply a downhill time trial on a short courseâusually lasting between two and six minutes. Competitors wear full-face helmets and sometimes body armor. Downhill has become a natural summer sport for ski resorts, many of which now have marked, graded runs and open ski lifts to transport the bikers to the top of the runs. The UCI runs a season-long World Cup and a world championship.

The original form of MOUNTAIN-BIKING, and still the most traditional variant of the sport, with its principles unchanged since the days of the REPACK downhill in California in the late 1970s. It is simply a downhill time trial on a short courseâusually lasting between two and six minutes. Competitors wear full-face helmets and sometimes body armor. Downhill has become a natural summer sport for ski resorts, many of which now have marked, graded runs and open ski lifts to transport the bikers to the top of the runs. The UCI runs a season-long World Cup and a world championship.

The Repack riders used the “clunkers” that evolved into the mountain bike, and later downhillers rode either conventional mountain bikes or customized variants. It was not until the 1990s that specialist downhill machines became widespread. These have large-diameter disc brakes, front and rear suspension with far more travel than machines used for cross-country and touring, and more laid-back frame design so that the rider can get his or her weight further back. More lightweight dual suspension and discs are now ubiquitious on all top-end mountain bikes; in these areas downhill has pushed development forward.

Downhill was included in the first UCI mountain-bike world championships at Durango, Colorado, in 1990: the winners were Greg Herbold of the US and Cindy Devine of Canada. The bike-handling element and need for upper-body strength has meant there has always been crossover with BMX, with one early champion the former BMX racer John Tomac. GREAT BRITAIN is surprisingly strong in the discipline. Steve Peat was world champion in 2009, while the union jack is flown by the Atherton family from Wales: Rachel, Geeâthe 2008 world championâand Dan.

V

ariants on mountain-bike downhill include

Super-D

, a mix of cross-country and downhill with uphill sections that discourage the use of downhill machines;

Freeride

, a test of riding skill scored for riding style, selection of trajectory, tricks, and time;

Dual-Slalom

, a knock-out event with two riders side by side on identical courses;

Four-Cross

, four riders starting together like BMX with an initial timed solo round for seeding, followed by knock-out rounds.

ariants on mountain-bike downhill include

Super-D

, a mix of cross-country and downhill with uphill sections that discourage the use of downhill machines;

Freeride

, a test of riding skill scored for riding style, selection of trajectory, tricks, and time;

Dual-Slalom

, a knock-out event with two riders side by side on identical courses;

Four-Cross

, four riders starting together like BMX with an initial timed solo round for seeding, followed by knock-out rounds.

Downhill venues include some of the same French Alpine resorts that host Tour de France stages, including l'Alpe d'Huez and Morzine, Italian ski resorts such as Bardonnechia and Pila, while in Liguria there are downhill courses that end by the Mediterranean. In Great Britain, most downhill courses are in Wales and Scotland, with a World Cup and world championship venue at Ben Nevis.

There are few comparable events in road cycling, although there is the Red Bull Descent, a timed downhill challenge using the hairpins that wind down from the Pyrenéan ski resort of Pla d'Adet. The 2009 winner was the Frenchman Fred Moncassin, a former stage winner in both the mountain-bike and road Tours de France.

BIZARRE

DOWNHILL FACTOID

DOWNHILL FACTOID

The Bosnian capital Sarajevo, which is ringed by mountains, has a downhill race that goes through streets on the steep slopes.

4

There is a curious subculture to downhill, in which speed record attempts are made on frozen ski-slopes by heavily protected downhillers, a fashion that caught on in the late 1990s inspired by Frenchman Fabrice Taillefer. These are fear-inspiring and very quick: the record is over 130 mph.

DRAISIENNE

Early bicycle, invented in 1817 by Baron Karl von Drais, Master of the Forests in the duchy of Baden, Germany, whose other inventions included a typewriter and a meat grinder. Made of wood, it consisted of two wheels joined by a frame with a seat for the rider, with the front wheel able to rotate freely so the machine could be steered. There were no pedals. It included a seat, luggage rack, and a “balancing board” on which the rider placed his elbows. The speeds attained by the Draisienne depended on the road surface and gradient, but it was found to be fourtimes faster than post-coaches.

Early bicycle, invented in 1817 by Baron Karl von Drais, Master of the Forests in the duchy of Baden, Germany, whose other inventions included a typewriter and a meat grinder. Made of wood, it consisted of two wheels joined by a frame with a seat for the rider, with the front wheel able to rotate freely so the machine could be steered. There were no pedals. It included a seat, luggage rack, and a “balancing board” on which the rider placed his elbows. The speeds attained by the Draisienne depended on the road surface and gradient, but it was found to be fourtimes faster than post-coaches.

The Draisienne was patented at the start of 1818 and launched in France later that year; by then there were four companies making similar machines in Germany, and others across Europe began copying the model.

In December 1818 a patent was registered in London by a carriage maker named Denis Johnson, for a “pedestrian curricle” made largely of iron and selling at 8 or 10 guineas, and based on the Draisienne design. The “hobby horse” was born and was rapidly taken up by Regency London; the wealthy would turn up at his two schools to be instructed in riding the machine. A drop-frame version was made for ladies to accommodate long skirts. So many people rode the hobby horses that they were banned from pavements in London; the craze spread to America, pushed by Johnson, but eventually died out.

Â

(SEE

BONESHAKER

FOR THE NEXT STAGE IN CYCLE DEVELOPMENT;

HIGH-WHEELER

AND

SAFETY BICYCLE

FOR LATER VARIANTS ;

BICYCLE

FOR A SUMMARY OF THE MACHINE'S DEVELOPMENT;

LEONARDO DA VINCI

FOR THE DEBATE OVER A POSSIBLE EARLY MACHINE)

BONESHAKER

FOR THE NEXT STAGE IN CYCLE DEVELOPMENT;

HIGH-WHEELER

AND

SAFETY BICYCLE

FOR LATER VARIANTS ;

BICYCLE

FOR A SUMMARY OF THE MACHINE'S DEVELOPMENT;

LEONARDO DA VINCI

FOR THE DEBATE OVER A POSSIBLE EARLY MACHINE)

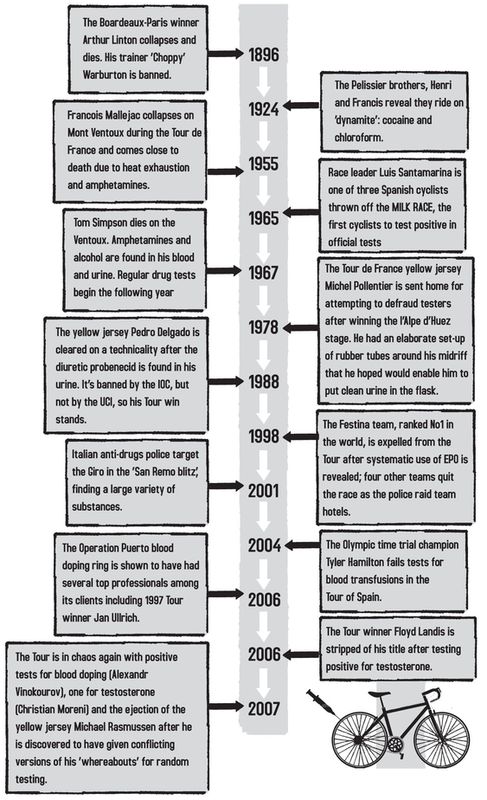

DRUGS

Cycle racing is one of the toughest endurance disciplines in sport, and a variety of illegal substances have been used over the years as cyclists have attempted to go farther and faster. Doping began with the marathon events of the 1890s, particularly the SIX-DAY races, where riders would use caffeine, strychnine, and arsenic. By the 1930s, drug-taking in cycling was so institutionalized that the rider contracts in the TOUR DE FRANCE stated that the cost of “stimulants, tonics and doping” had to be paid by the riders themselves, according to historian Benjo Maso.

Cycle racing is one of the toughest endurance disciplines in sport, and a variety of illegal substances have been used over the years as cyclists have attempted to go farther and faster. Doping began with the marathon events of the 1890s, particularly the SIX-DAY races, where riders would use caffeine, strychnine, and arsenic. By the 1930s, drug-taking in cycling was so institutionalized that the rider contracts in the TOUR DE FRANCE stated that the cost of “stimulants, tonics and doping” had to be paid by the riders themselves, according to historian Benjo Maso.

Ironically in view of the mythology that surrounds drug-taking, the effects have often been counterproductive rather than performance enhancing. Cyclists have ended up with long-term injuries and mental problems through drug takingânot to mention the deathsâwhile recent developments in professional cycling suggest that winning the biggest events “clean” thanks to proper training is probably more straightforward.

Alcohol

was often used up to the 1970s for its painkilling and euphoric effects. TOM SIMPSON was seen drinking brandy shortly before his death in the 1967 Tour de France.

was often used up to the 1970s for its painkilling and euphoric effects. TOM SIMPSON was seen drinking brandy shortly before his death in the 1967 Tour de France.

Amphetamines

became popular during the 1950s after large amounts of Benzedrine produced for the airmen of the Second World War came onto the market. Its euphoric effect enabled a cyclist to ignore the pain, but it is highly addictive so regular users ended up taking more and more to get the same effect. In addition, the feeling of invincibility reported by amphetamine users could lead to crashes and bizarrely timed attacks that resulted in defeat. After Simpson's death, testing was brought in and the use of amphetamines in major events declined, although the Irish pro Paul Kimmage wrote that it was widespread in lesser races as late as the 1980s.

became popular during the 1950s after large amounts of Benzedrine produced for the airmen of the Second World War came onto the market. Its euphoric effect enabled a cyclist to ignore the pain, but it is highly addictive so regular users ended up taking more and more to get the same effect. In addition, the feeling of invincibility reported by amphetamine users could lead to crashes and bizarrely timed attacks that resulted in defeat. After Simpson's death, testing was brought in and the use of amphetamines in major events declined, although the Irish pro Paul Kimmage wrote that it was widespread in lesser races as late as the 1980s.

Anabolic agents

were most used in the 1970s and 1980s.

were most used in the 1970s and 1980s.

Other books

The Rabbit Back Literature Society by Pasi Ilmari Jaaskelainen

Seti's Heart by Kelly, Kiernan

Freelancer by Jake Lingwall

What Remains by Radziwill, Carole

How to be a Pirate's Dragon (Hiccup) by Cressida Cowell

The Old Wolves by Peter Brandvold

Easy as One Two Three (Emma Frost) by Rose, Willow

Blood, Body and Mind by Barton, Kathi S.

Honey Does by Kate Richards