Cyclopedia (20 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

An annual Brompton world championship is run in which the riders wear suit jackets, cycle shorts, and cycle helmets and have a Le Mansâtype start, running to unfold their bikes. Bizarrely, a regular contestant is the Spaniard Roberto Heras, disqualified from first place in the 2004 VUELTA A ESPAÃA for doping.

Â

FOREIGN LEGION

A term coined by the Australian journalist Rupert Guinness. It was the title for his book published in 1993, which traced the fortunes of the group of English-speaking professional cyclists who opened up the European-dominated sport during the 1980s. In essence they made cycling truly international. The bulk of legionnaires passed through the elite Parisian amateur club Association Cycliste de Boulogne-Billancourt (ACBB), which was sponsored by PEUGEOT as a feeder club to their professional team. PHIL ANDERSON, Graham Jones, ROBERT MILLAR, SEAN YATES, and STEPHEN ROCHE all took this route between 1979 and 1983.

A term coined by the Australian journalist Rupert Guinness. It was the title for his book published in 1993, which traced the fortunes of the group of English-speaking professional cyclists who opened up the European-dominated sport during the 1980s. In essence they made cycling truly international. The bulk of legionnaires passed through the elite Parisian amateur club Association Cycliste de Boulogne-Billancourt (ACBB), which was sponsored by PEUGEOT as a feeder club to their professional team. PHIL ANDERSON, Graham Jones, ROBERT MILLAR, SEAN YATES, and STEPHEN ROCHE all took this route between 1979 and 1983.

While Jones's career never took off in spite of his undoubted class, Anderson was the first Australian to wear the yellow jersey in the Tour de France, the first to win a CLASSIC, and the first to win a Tour stage. Millar was the first Briton to win a major award in the Tour, taking the mountains jersey in 1984 while Roche achieved the golden triple in 1987: GIRO D'ITALIA, TOUR DE FRANCE, and world championship.

Of the non-ACBB riders, SEAN KELLY won the points jersey of the Tour a record four times between 1983 and 1989 and was world number one for five years, while GREG LEMOND pioneered the sport in America with his Tour win in 1986. Between them they paved the way for the first American team to start the Tour, 7-Eleven in 1986, and the first British squad, ANC-Halfords in 1987. Together with the arrival of cyclists from COLOMBIA at the Tour in 1983, their influence helped to transform the sport within a decade.

Â

(SEE ALSO

AUSTRALIA

,

IRELAND

,

GREAT BRITAIN

,

ROAD RACING

,

UNITED STATES

)

AUSTRALIA

,

IRELAND

,

GREAT BRITAIN

,

ROAD RACING

,

UNITED STATES

)

FOSTER FRASER, John

(b. England, 1868, d. 1936)

One of the first round-the-world cyclists, who set off with two friends, Edward Lunn and F. H. Lowe, to circumnavigate the globe between 1896 and 1898. Their route took in Persia, the Indian sub-continent from Karachi to Calcutta, through Burma to China and Shanghai, thence to Japan, San Francisco, and across the United States, a total of 19,237 miles.

Foster Fraser's account of the trip,

Round the World on a Wheel

, was published in 1899 and reissued in 1982; it is one of the first and one of the finest cycle travelogues. It features encounters with Russian officials straight out of Tolstoy, riotous arguments with Cossacks in the Caucasus, a trip to a medieval dungeon and the Shah's palace in Iran, not to mention near-death from hypothermia in the Hindu Kush.

Round the World on a Wheel

, was published in 1899 and reissued in 1982; it is one of the first and one of the finest cycle travelogues. It features encounters with Russian officials straight out of Tolstoy, riotous arguments with Cossacks in the Caucasus, a trip to a medieval dungeon and the Shah's palace in Iran, not to mention near-death from hypothermia in the Hindu Kush.

The tone is smugly Victorianâ“The Georgians are a lazy race, much addicted to gourmandising,” “being Europeans and strangers we of course ran the gauntlet of all the halt, lame and blind in Teheran”âbut there is an exquisite irony in the fact that international conflicts, officialdom, and terrorism would make such a journey far more risky in the 21st century.

Â

(SEE

BOOKSâTRAVEL

FOR OTHER INTREPID CYCLISTS WHO HAVE WRITTEN ABOUT THEIR ADVENTURES)

BOOKSâTRAVEL

FOR OTHER INTREPID CYCLISTS WHO HAVE WRITTEN ABOUT THEIR ADVENTURES)

FRAMESâDESIGN

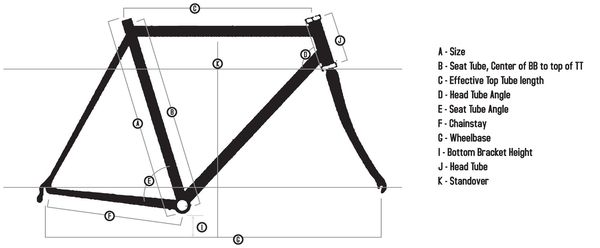

Frame size is usually expressed by measuring the seat tubeâeither center to center, from the middle of the bottom bracket to the middle of the seat lug, or center to top. The advent of smaller frames with sloping top tubes means that a more important measurement now is the distance between the center of the bottom bracket and the top of the saddle.

Frame size is usually expressed by measuring the seat tubeâeither center to center, from the middle of the bottom bracket to the middle of the seat lug, or center to top. The advent of smaller frames with sloping top tubes means that a more important measurement now is the distance between the center of the bottom bracket and the top of the saddle.

Another complication is that bottom bracket height can vary, particularly with cyclo-cross machines and children's bikes, affecting the “stand-over” height.

Frame performance depends on several factors. Handling stability depends mainly on the amount of “trail”âthe distance between a notional line taken down the steerer tube and the point where the front tire makes contact with the road. The extent of trail depends on the angle of the head tube, and the rake of the forks, which may be curved or bent at the fork crownâthe shallower the head angle and the longer the rake, the greater the trail. More trail equals more stability, which in riding terms translates into whether a bike can be ridden safely with hands off the bars, and for how far, and the degree of comfort over bumps.

Another key element is seat-tube angle, usually measured compared to a notional horizontal line, in some cases to the top tube. The usual range is between 69 and 74 degrees; the lower the number, the shallower the angle, and the less upright the seat tube. Bikes with shallower angles are usually more stable and comfortable, and may well have longer seat-and chain-stays to give a longer wheelbase and greater comfort;

bikes with tighter angles and a shorter rear triangle are more responsive, but are less forgiving on bumpy roads.

bikes with tighter angles and a shorter rear triangle are more responsive, but are less forgiving on bumpy roads.

The forward reach of the bikeâthe distance between the tip of the saddle and the center of the handlebarsâis a key factor in determining comfort, whether the rider is hunched up or stretched out, and aerodynamics, the extent to which the torso is flat or upright. Forward reach depends on top tube length and seat angle, the degree to which the saddle is pushed forward or back, and the length of the stem.

FRAMESâMAKERS

The refinement of steel tubing meant that the handbuilt road-racing or track frame eventually became a mini art form. The lugs that hold the tubes together and provide a surface for bonding to take place were cut into forms that varied from basic curves to the elaborate filigree that was the trademark of the East London firm Hetchins.

The refinement of steel tubing meant that the handbuilt road-racing or track frame eventually became a mini art form. The lugs that hold the tubes together and provide a surface for bonding to take place were cut into forms that varied from basic curves to the elaborate filigree that was the trademark of the East London firm Hetchins.

In Great Britain and Northern Italy, artisan frame makers turning out a few hundred bikes a year for the racing and high-end touring markets were relatively widespread until the 1990s, when the nature of the cycle trade changed with the arrival of carbon-fiber and aluminumâwhich were less suited to small producersâand compact frames that, the manufacturers claimed, offered equal performance for lower price and less hassle. Some makers now cater for both, offering a number of custom-made machines but relying on off-the-rack bikes for most of their trade.

Best-known North American makers include:

Richard Sachs

, Chester, Connecticut. The ultimate in the United States; served his apprenticeship at Witcomb Cycles in London almost 40 years ago. “At Richard Sachs

Cycles, I am the work force,” says his website.

, Chester, Connecticut. The ultimate in the United States; served his apprenticeship at Witcomb Cycles in London almost 40 years ago. “At Richard Sachs

Cycles, I am the work force,” says his website.

Mariposa

, Toronto. Canada's most prominent framebuilder. Their mainstay Mike Barry is now retired so production is limited to a few special projects.

, Toronto. Canada's most prominent framebuilder. Their mainstay Mike Barry is now retired so production is limited to a few special projects.

Spectrum Cycles

, LeHigh Valley, Pennsylvania. Two-man operation run by Tom Kellogg and Mike Duser; Kellogg has been building since 1976. Collaborated in late 1980s with titanium makers Merlin, with whom the company still works.

, LeHigh Valley, Pennsylvania. Two-man operation run by Tom Kellogg and Mike Duser; Kellogg has been building since 1976. Collaborated in late 1980s with titanium makers Merlin, with whom the company still works.

Moots Cycles

, Steamboat Springs, Colorado. Founded by Kent Eriksen in 1981, one of the early mountain bike makers, now produces a wide variety of handbuilt titanium frames. Logo is a distinctive, lovable, crocodile.

, Steamboat Springs, Colorado. Founded by Kent Eriksen in 1981, one of the early mountain bike makers, now produces a wide variety of handbuilt titanium frames. Logo is a distinctive, lovable, crocodile.

Roland Della Santa

, Reno, Nevada. Another builder with over 35 years experience, Della Santa most notably made frames for GREG LEMOND.

, Reno, Nevada. Another builder with over 35 years experience, Della Santa most notably made frames for GREG LEMOND.

Independent Fabrication

, Somerville, Massachusetts. Founded 1995, employee-owned, and best known for its steel frames; the crowned IF logo is one of the most distinctive in the world.

, Somerville, Massachusetts. Founded 1995, employee-owned, and best known for its steel frames; the crowned IF logo is one of the most distinctive in the world.

Best-known British makers include:

Hetchins

(Tottenham, London; then Southend). Produced frames with delicately curved seat stays, seat tubes, and S-shaped chainstaysâthe legendary “Curly.” Their machines were given Latin names such as Nulli Secundus and Magnum Bonum and are now collectors' items. The original makers ran from the 1920s to the late 1980s, but the frames are still made under license.

(Tottenham, London; then Southend). Produced frames with delicately curved seat stays, seat tubes, and S-shaped chainstaysâthe legendary “Curly.” Their machines were given Latin names such as Nulli Secundus and Magnum Bonum and are now collectors' items. The original makers ran from the 1920s to the late 1980s, but the frames are still made under license.

Bates

(East London). Another now defunct maker, who produced a bent fork design known as the Diadrant and used “Cantiflex” frame tubing, which featured an oversized central section to reduce frame flex. Founded by brothers Eddie and Horace, with a bat as the logo, they were one of London's leading makers from the 1930s through the 1950s, although the brothers eventually went their separate ways. Like Hetchins, they are now made under license.

(East London). Another now defunct maker, who produced a bent fork design known as the Diadrant and used “Cantiflex” frame tubing, which featured an oversized central section to reduce frame flex. Founded by brothers Eddie and Horace, with a bat as the logo, they were one of London's leading makers from the 1930s through the 1950s, although the brothers eventually went their separate ways. Like Hetchins, they are now made under license.

Mercian Cycles

(Derby). One of the last remaining companies to make hand-built frames in any volume. Opened in 1946, and known for their fine finishes, they keep frame design records dating to the 1970s so their customers can refer back if they want a new frame.

(Derby). One of the last remaining companies to make hand-built frames in any volume. Opened in 1946, and known for their fine finishes, they keep frame design records dating to the 1970s so their customers can refer back if they want a new frame.

Bob Jackson

(Leeds). Variously marketed under the names JRJ and Merlin; produced frames under license for Hetchins in the 1980s and is still producing them today after over 70 years. Like Mercian, fine finishes are a specialty.

(Leeds). Variously marketed under the names JRJ and Merlin; produced frames under license for Hetchins in the 1980s and is still producing them today after over 70 years. Like Mercian, fine finishes are a specialty.

Chas Roberts

(Croydon). London's leading custom-made frame builder, set up in the early 1960s by Charlie, the father of the current owner, Chas, who had to train as a frame maker for 10 years before he met the standard the company demanded.

(Croydon). London's leading custom-made frame builder, set up in the early 1960s by Charlie, the father of the current owner, Chas, who had to train as a frame maker for 10 years before he met the standard the company demanded.

Â

Â

FRAMESâMATERIALS

Early cycle frames were built of wood or iron; the key development came in 1897 when Alfred Reynolds patented double-butted tubing in which the ends of the tubes had thicker walls than the middle, improving the strength-to-weight ratio.

Early cycle frames were built of wood or iron; the key development came in 1897 when Alfred Reynolds patented double-butted tubing in which the ends of the tubes had thicker walls than the middle, improving the strength-to-weight ratio.

Thirty-eight years later Reynolds would go on to produce the definitive steel frame tube, initially for lightweight motorcycles. Reynolds 531 was named after the ratio of the other materials used in the steel alloy: manganese, molybdenum, and silica. The British company dominated the tubing market for many years: 27 out of 31 TOUR DE FRANCE winners between 1958 and 1989 rode on steel tubes such as 531 and the much thinner and lighter 753. By the golden jubilee of 531 in 1985, Reynolds estimated that the tubing had gone into 20 million frame sets worldwide. The other major steel tubing name came from Italy, where Angelo Colombo began making steel cycle tubing in 1919 and produced butted tubes from 1930.

FRAME FACTOID

In 2007, to coincide with the Tour de France start in London, top designer Paul Smith produced a range of jeans branded 531, taking the name from Reynolds' iconic tubing. Smith was a racing cyclist in the 1960s before a crash curtailed his career, but he remained intensely interested in the sport.

4

Aluminium frames were produced as early as the 1890s, but it took the best part of 80 years for frame makers to master the process of joining the tubes. In the 1970s, Italian firm ALAN (from the acronym ALuminium ANodised) made attractive, light, lugged frames which remain popular with cyclo-cross riders today. But steel remained the material of choice until the advent of the MOUNTAIN BIKE and the perfection of welding processes in the 1980s. Oversize aluminiumâstronger, yet lighter tubes, in spite of the increased sizeâcame from mountain-biking and was popularized initially by the Cannondale company from the US, who sponsored the Italian sprinter Mario Cipollini in the early 1990s.

Titanium frames appeared in the mid-1950s and were used in the Tour de France by the Spaniard Luis Ocana in the 1970s, but they were sloppy and fragile; again the mountain-bike boom was the spur for the perfection of the product. Again, the initial boost came from the US, where Merlin and Litespeed were turning out jewel-like products by the early 1990s.

Carbon-fiber composite frames appeared in the 1980s, when companies like Vitus made frames of carbon tubes with aluminium lugs, and have been gaining in popularity since the 1990s, spurred on by the arrival of companies like Giant, Specialised, and Trek in professional cycling; in the early 1990s GREG LEMOND's bike company produced carbon frames with web-like joins. The process sounds simpleâsheets of the fibers are bonded with epoxy resin and then bakedâbut it has

taken time to perfect. Much of the impetus has come from military technology, where carbon fibers are used for lightweight armoring, for example bullet-proof pads for helicopters.

taken time to perfect. Much of the impetus has come from military technology, where carbon fibers are used for lightweight armoring, for example bullet-proof pads for helicopters.

Other books

The Holiday Hoax by Jennifer Probst

No me iré sin decirte adónde voy by Laurent Gounelle

The Girls in the High-Heeled Shoes by Michael Kurland

Ivy and Bean Doomed to Dance by Annie Barrows

Life On the Refrigerator Door by Alice Kuipers

Baby, Come Home by Stephanie Bond

Pack Mistress #3 (Quick 'n' Dirty Erotic Paranormal Romance) by Evelyn Lafont

The Sorcerer's Vengeance: Book 4 of the Sorcerer's Path by Brock Deskins

Forty Things to Do Before You're Forty by Alice Ross

The Sleuth Sisters by Pill, Maggie