Cyclopedia (22 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

Â

contre la montre:

time trial.

time trial.

Â

critérium:

race on a short circuit around a town.

race on a short circuit around a town.

Â

directeur sportif:

team manager.

team manager.

Â

domestique

(cf British water-carrier, Italian

gregario

): lesser rider in a team who works for the leader.

(cf British water-carrier, Italian

gregario

): lesser rider in a team who works for the leader.

Â

dossard:

race number.

race number.

Â

echelon:

diagonal formation for combating sidewind in which the cyclists ride through and off.

diagonal formation for combating sidewind in which the cyclists ride through and off.

Â

lanterne rouge:

last man in a stage race, so called because he was awarded a red lantern such as might be put on the back of a freight train.

last man in a stage race, so called because he was awarded a red lantern such as might be put on the back of a freight train.

Â

maillot jaune:

yellow jersey worn by leader of a stage race (cf

à pois

,

vert

,

blanc

).

yellow jersey worn by leader of a stage race (cf

à pois

,

vert

,

blanc

).

Â

musette:

cloth bag (literally “nosebag”) handed up at feed station (

ravitaillement

) containing

bidons

and race food.

cloth bag (literally “nosebag”) handed up at feed station (

ravitaillement

) containing

bidons

and race food.

Â

neutralisation:

spell in a race when the riders are on their bikes but not actually racing. Most stages of the Tour de France are “neutralised” from the formal start in a town center to the actual start on the outskirts of town; track races may be “neutralised” after a crash.

spell in a race when the riders are on their bikes but not actually racing. Most stages of the Tour de France are “neutralised” from the formal start in a town center to the actual start on the outskirts of town; track races may be “neutralised” after a crash.

Â

nocturne:

a criterium run at night. In smaller venues this means at least one stretch in the dark.

a criterium run at night. In smaller venues this means at least one stretch in the dark.

Â

peloton:

main group in a race, in

main group in a race, in

English “the bunch.”

Â

prime:

intermediate prize of any kind, also a bonus given for performance by a team or club.

intermediate prize of any kind, also a bonus given for performance by a team or club.

Â

prologue:

brief opening time trial in a stage race.

brief opening time trial in a stage race.

Â

ravitaillement (abbr. ravito):

feed zone where

musettes

are handed up by

soigneurs

.

feed zone where

musettes

are handed up by

soigneurs

.

Â

rouleur:

a racing cyclist with stamina who can mix it with the best all day and be in there at the finish.

a racing cyclist with stamina who can mix it with the best all day and be in there at the finish.

Â

signature:

where the riders register and receive numbers, the English term is sign-on.

where the riders register and receive numbers, the English term is sign-on.

Â

soigneur:

team assistant who provides race food and massage. Anglicized as swanee, also carer.

team assistant who provides race food and massage. Anglicized as swanee, also carer.

Â

speaker:

announcer at major races who introduces the riders at the sign-on. (See MANGEAS to read more about the voice of French racing.)

announcer at major races who introduces the riders at the sign-on. (See MANGEAS to read more about the voice of French racing.)

Â

voiture balai:

vehicle that drives at back of race convoy to “sweep up” riders who drop out. Anglicized as broom wagon.

vehicle that drives at back of race convoy to “sweep up” riders who drop out. Anglicized as broom wagon.

G

GARIN, Maurice

Born:

Aosta, Italy, March 23, 1871

Aosta, Italy, March 23, 1871

Â

Died:

Lens, France, February 18, 1957

Lens, France, February 18, 1957

Â

Major wins:

Tour de France 1903, 3 stage wins; ParisâRoubaix 1897â8; ParisâBrestâParis 1901; BordeauxâParis 1902

Tour de France 1903, 3 stage wins; ParisâRoubaix 1897â8; ParisâBrestâParis 1901; BordeauxâParis 1902

Â

Nicknames:

the White Bulldog, the Chimney Sweep

the White Bulldog, the Chimney Sweep

Â

The winner of the first TOUR DE FRANCE in 1903, and the main protagonist in its first great scandal, was one of tens of thousands of boys from the Alps who trekked up to Paris in the late 19th century to earn a living cleaning the capital's chimneys.

Born on the Italian side of the border in Aosta, Garin was one of the best distance racers of the time: he won two early editions of the PARISâROUBAIX classicâwhich finished in the town where he ran a cycle shopâas well as 24-hour races in Paris and Liège, BordeauxâParis and PARISâBRESTâPARIS in 1901. He also set a record for 500 km in 1895. Garin won the first stage of the Tour, the 467 km from Paris to Lyon, at an average speed of 26 kph, and led the race throughout, losing two and a half kilograms over the three weeks.

Garin was also winner of the Tour de France in 1904, but was disqualified after a four-month investigation by the Union Vélocepédique Française that led to 29 of the field being sanctioned. The report was never published but the riders' offences included holding onto cars, taking shortcuts, swapping race numbers to avoid controls, colluding with fellow competitors, and catching trains. The scandal led Tour organizer HENRI DESGRANGE to write that his race had been destroyed.

Such charges were common in races of the HEROIC ERA, in which

the riders spent long periods out in the countryside meaning it was impossible for officials to keep tabs on them. In the 1903 race, Garin avoided being beaten up by a rival's supporter in the depths of night only by pretending he was someone else. Ironically, he was a victim of the worst episode of the 1904 race, when a mob held up the riders near St-Ãtienne, demanding that the local rider André Fauré be allowed to win. He was hit on the head with a bottle, and the mob dispersed only when the race organizer Géo Lefèvre turned up and fired pistol shots into the air.

the riders spent long periods out in the countryside meaning it was impossible for officials to keep tabs on them. In the 1903 race, Garin avoided being beaten up by a rival's supporter in the depths of night only by pretending he was someone else. Ironically, he was a victim of the worst episode of the 1904 race, when a mob held up the riders near St-Ãtienne, demanding that the local rider André Fauré be allowed to win. He was hit on the head with a bottle, and the mob dispersed only when the race organizer Géo Lefèvre turned up and fired pistol shots into the air.

Garin was banned for two years and raced again only once, in the 1911 ParisâBrestâParis. But he had time to invest the prize money from the 1904 Tour win in a garage in the northern France town of Lens, where he worked until his death. Historian Les Woodland described him as “an old man, a bit stooped” but still with the enormous handlebar moustache of his youth.

He is buried in section F3 of the Cimetière Est off rue Constant Darras between Lens and Sallaumines; there is no formal memorial. The assistant gravedigger there, Maurice Vernaldé, told Woodland that Garin admitted cheating in the 1904 Tour: “He used to laugh and say âWell I was young . . .' Maybe at the time he said he didn't but when he got older and it didn't matter so much.”

GEARS

Although experimentation with multiple gears began in the days of the velocipede, the first bicycles used single fixed gears, in which the transmission is directly linked to the driving wheel, with no possibility of freewheeling. On long descents riding a high-wheeler, the rider simply took his feet off the pedals, put them on pegs sticking out of the frame, and hoped for the best. Uphill, he or she would walk.

Although experimentation with multiple gears began in the days of the velocipede, the first bicycles used single fixed gears, in which the transmission is directly linked to the driving wheel, with no possibility of freewheeling. On long descents riding a high-wheeler, the rider simply took his feet off the pedals, put them on pegs sticking out of the frame, and hoped for the best. Uphill, he or she would walk.

The first hub gearsâwhich use different sized cogs within

the hub to create different ratiosâappeared in 1891. Freewheels were invented around 1897, with a clutch bearing enabling the rear wheel to run free of the gear sprocket. There were many attempts at different kinds of gearsâepicyclic, bichain, multiple chainwheels, multicog, bottom bracket gears, to name just a fewâbut while English cyclists stuck to the hub gears patented by Sturmey Archer in 1902 and made by RALEIGH, the French went for the derailleur.

the hub to create different ratiosâappeared in 1891. Freewheels were invented around 1897, with a clutch bearing enabling the rear wheel to run free of the gear sprocket. There were many attempts at different kinds of gearsâepicyclic, bichain, multiple chainwheels, multicog, bottom bracket gears, to name just a fewâbut while English cyclists stuck to the hub gears patented by Sturmey Archer in 1902 and made by RALEIGH, the French went for the derailleur.

The bodies that ran cycle racing restricted technical developmentâled by the conservative HENRI DESGRANGEâand so the impetus for the derailleur gear came from cycle-tourists, led by the French journalist Paul de Viviès (who wrote in his magazine

Le Cycliste

under the pen name VÃLOCIO) and his close circle of friends around the central France town of St-Ãtienne.

Le Cycliste

under the pen name VÃLOCIO) and his close circle of friends around the central France town of St-Ãtienne.

Vélocio experimented with almost every kind of gear as soon as it entered the market and wrote up the experiments in his magazine. The first mention of a derailleur mechanism was in 1908 or 1909, and about this time rear gear mechanisms began to be produced that had some of the elements that still feature today: a mechanism to push the chain from one sprocket to another and a long chain running through a tension spring and pulley to take up the slack as the sprocket size changes.

In 1912, Vélocio's friend Joanny Panel, maker of the Chemineau bike, rode the TOUR DE FRANCE using a six-speed derailleur gear system that resembled designs that would stay in use for half a century: a cylinder with a short sliding shaftâthe “plunger”âpushed inward by a spring, and pulled outward by a short chain on the end of a control cable. The Chemineau gear was still being produced in 1946.

The first popular derailleur was the Le Cyclo two-speed gear, made by another of Vélocio's friends, Albert Raimond, which appeared in 1924. In 1931 the

Simplex company brought out a four-speed model that looked similar, and, critically, their owner Lucien Juy won over the remaining cynics among the racing fraternity, pushing sales over 50,000 annually. Also in the 1930s, the first front derailleurs appeared; they would not become popular until after the Second World War, however.

Simplex company brought out a four-speed model that looked similar, and, critically, their owner Lucien Juy won over the remaining cynics among the racing fraternity, pushing sales over 50,000 annually. Also in the 1930s, the first front derailleurs appeared; they would not become popular until after the Second World War, however.

In 1936, Henri Desgrange stepped down as Tour de France organizer, and the way was open for the use of geared bikes in the race from 1937; until then, the riders had used wheels with two sprockets on either side; to change gear they would stop, take their rear wheel out, and turn it around. “You had to do it at the right moment,” the 1937 winner Roger Lapébie said. “You could lose a race if you didn't change gear at the right moment. If a good rider stopped to change gear, everyone might attack together.”

Most of the yellow bikes issued to the Tourmen were fitted with Super Champion gears made by the Swiss track racer Oscar Egg, in which the chain was “derailed” by a pushing mechanism that hung from the chainstay, with the tension pulley and spring hanging from the bottom bracket. They appeared primitive compared to the Simplex, but offered a wide range of gears. The Italians used a similar looking gear called the Vittoria.

Post-war, it was TULLIO CAMPAGNOLO who made the next breakthrough when he produced the first parallelogram derailleur, the Gran Sport, in 1950. Two other companies had produced parallelogram models, and he had bought the patent rights for one, made by Italian company Ghigghini, but his was the design that would become the industry standard. Campag' would dominate the high-end racing market for the next 35 years, as derailleur gears became lighter and slicker, mostly based on the original Gran Sport.

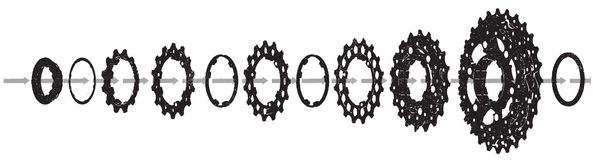

The next developments came in 1975 from Japan's SHIMANO, who began producing indexed gearsâwhere the derailleur cable jumped into preset

positions so that shifting was predictable. In 1978 Shimano made their first freehub, which replaced a single freewheel block with individual sprockets on a splined body giving total freedom of sprocket choice.

positions so that shifting was predictable. In 1978 Shimano made their first freehub, which replaced a single freewheel block with individual sprockets on a splined body giving total freedom of sprocket choice.

Gear Size

=

The system of measuring a gear dates back to the days of the high-wheeler and should be thought of in terms of a notional front wheel powered directly by the legs: a 60-inch gear (for a two-foot six-inch inside leg) would have been large for an old ordinary, but is now a climbing gear for most fit cyclists.

The imperial gear size is calculated by taking the diameter of the rear wheel in inches, multiplying it by the number of teeth on the chainwheel, and dividing it by the number of teeth on the rear cog. The lower the figure (i.e., the smaller the notional front wheel), the lower the gear. For example, on a 27-inch wheel, 48 Ã 19 = 68 inches, a medium-size gear.

Team mechanics and racers tend to think simply in terms of the teeth on the front chain ring and rear sprocket, without worrying about notional front wheels: e.g., 52 Ã 13 is a sprinting gearâ108 inches for that notional imperial front wheelâwhile at the other end of the spectrum 39 Ã 23 is a climbing gear.

Gear size matters for various reasons. In TRACK RACING in particular, gears need to be adjusted by tiny increments to take into account air temperature, form, and the speed of the track surface. Most track racers carry a variety of fixed sprockets and chainwheels with them. In GREAT BRITAIN, young riders are limited to gears up to a certain size to avoid putting strain on developing tendons and muscles.

The arrival of indexed gearing in high-end road groups from 1985 meant that changing development then focused on the levers, change quality, and the number of sprockets rather than the derailleurs. 1989 saw Shimano's first prototype STI brake-lever gear changers used by the 7-Eleven team; they entered the market the following year and Campagnolo didn't catch up with their Ergopower

levers until 1992, giving the Japanese company a head start that enabled it to establish a dominant position in the market. Off-road, indexed top-of-the-bar thumbshifters gave way to dual levers below the bar (Rapidfire from Shimano, X-Press from SunTour) with newcomers Sram bringing out the Gripshift, based on the cylindrical handgrip at the end of the bar, from 1988.

levers until 1992, giving the Japanese company a head start that enabled it to establish a dominant position in the market. Off-road, indexed top-of-the-bar thumbshifters gave way to dual levers below the bar (Rapidfire from Shimano, X-Press from SunTour) with newcomers Sram bringing out the Gripshift, based on the cylindrical handgrip at the end of the bar, from 1988.

Other developments have included tweaks in sprocket and chain ring design to make changing more rapid and reliable with thinner chains as sprocket numbers have increased from 6âthe standard in the early 1980sâto 11. While Mavic was the first to experiment with electronic shifting with the 1999 Mektronic, Shimano appears to have achieved the first reliable models with 2008's DuraAce. The smaller derailleur makers such as SunTour, Huret, and Sachs were killed off by Shimano's move to integrated transmission, where all the components are interdependent and cannot be used with those of other companies; Campagnolo followed suit.

In essence, the gear market in the early 2000s has been dominated by Shimano, thanks mainly to the STI breakthrough, with Campagnolo offering minor opposition, and Sramâwho had acquired component makers such as Gripshift, Sachs, Huret, and Sedisâintroducing their own brake-gear levers, Double-Tap, in 2007, thus providing proper competition for the big two.

Â

GHOST BIKES

In some 40 countries worldwide, memorials made of white-painted bicycles can be seen on roadsides at places where cyclists have been killed by motor vehicles. The movement is strongest in the United States, where the first ghost bikes were created purely for artistic reasons by San Francisco artist Jo Slota, who in 2002 began painting the abandoned bikes and parts that littered the city white and posting photos of them on a website.

In some 40 countries worldwide, memorials made of white-painted bicycles can be seen on roadsides at places where cyclists have been killed by motor vehicles. The movement is strongest in the United States, where the first ghost bikes were created purely for artistic reasons by San Francisco artist Jo Slota, who in 2002 began painting the abandoned bikes and parts that littered the city white and posting photos of them on a website.

Now, however, “they serve as reminders of the tragedy that took place on an otherwise anonymous street corner, as quiet statements of cyclists' right to safe travel,” according to a website that lists the memorials. Sometimes they are put up overnight so as to create a dramatic effect the following morning, as if they have appeared out of nowhere.

The bikes used are junked machines, with parts such as cables, brakes, and pedals removed so that they are less attractive to thieves and easier to paint. Sometimes they are mangled or damaged, as they would be in an accident. The Ghost Bikes website gives advice on painting the bike, creating placards, and locking it in situ, and even recommends that the bikes be carried to the site rather than wheeled to avoid wearing the paint from the tires and perhaps reducing the effect.

(SEE ALSO

MEMORIALS

)

MEMORIALS

)

Other books

Most Eagerly Yours by Chase, Allison

Full Throttle by Kerrianne Coombes

Family Skeletons by O'Keefe, Bobbie

Burning Rivalry (Trevor's Harem #2) by Aubrey Parker

Come and Join the Dance by Joyce Johnson

Capturing Paris by Katharine Davis

Heart's Reward by Donna Hill

Rocketship Patrol by Greco, J.I.

Grayslake: More than Mated: Bear Up (Kindle Worlds Novella) by Mina Carter

A Deadly Web by Kay Hooper