Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight (34 page)

Read Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight Online

Authors: Linda Bacon

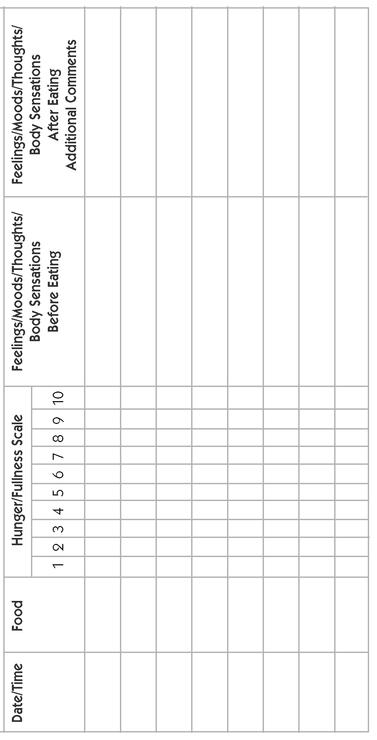

A journal can help you recognize hunger and fullness and identify patterns between eating and your physical state, emotions, thoughts, and moods. These patterns can eventually reveal how hunger and satisfaction manifest in your body.

In case the thought of a food journal conjures up bad feelings, let me alleviate your fears. This log is not a food journal like so many diet programs use to help you control the quantity and quality of food you eat, with the typical result being beating yourself up. Instead, your task is to be a nonjudgmental fact-finder. The goal is to explore whether the timing, quantity, and quality of foods you eat are truly satisfying and to figure out how to make your eating habits more enjoyable.

The Hunger/Fullness journal is provided on page 195. I recommend you make a copy of the chart and carry one with you when you leave the house and leave one in the kitchen.

Before you eat, put an X in the pre-eating box that describes how hungry you are. Also note your mood, thoughts, physical sensations, and emotions. Jot down anything that stands out in your mind that might be related to your degree of hunger or your appetite. What is your energy level? Notice any physical sensations in your body? Is your mind focused or wandering? Are you happy, sad? If you cannot identify your emotions or mood, is there something particular that you are thinking about? If you are not sure if some of these are related to hunger or appetite, write them anyway.

After you eat, rate how full you feel by putting an X in the post-eating rating box, again describing your mood, thoughts, and physical sensations. Draw a line connecting the Xs so you can see how much your hunger level changed before and after eating.

Are you resistant to trying this out? Study participants sure were! But trust me on this one: it’s a really valuable learning experience. You never know what will come up if you just let it flow, and writing stream-of-consciousness is often a great strategy to get around your inner censor.

Journaling can help you note common feelings that are your personal experience of hunger. Without journaling, you might not notice that certain sensations reappear consistently. For instance, one woman noticed a few mentions of being particularly tempted by the smells of restaurants as she drove by. These observations always appeared several hours after she had last eaten. She realized that a strong aspect of her hunger signal was that her senses, particularly smell, were heightened. From then on, she relied on her nose to tell her when it was time to eat!

Eating and Its Relation to Moods, Thoughts, Body Sensations, and Emotions: A Journal

Only you can determine when and how much to eat. The purpose of this journal is to figure out what is most satisfying for you. Your task is to look for the patterns to help you to respond to these questions:

1. What does hunger feel like to you and how does it progress?

2. What does fullness feel like to you and how does it progress?

3. What degree of hunger do you feel best responding to? Does the context matter?

4. At what level of fullness do you feel most content? Does the context matter?

Some patterns you may identify are listed below. See where you are.

There are two common reasons for this. Maybe you don’t allow yourself to get hungry because you eat before you’re hungry. In my study, one participant told me she thought that if she waited until she “felt” hungry, she’d eat until she exploded. It makes sense she would feel this way after believing for so long that she couldn’t trust her body. But recognize that there is nothing magical about getting hungry. Your body needs fuel, and hunger sensations are its way of asking for it. It will also feel satisfied, and it will let you know that as well. If you don’t give in and let yourself feel hungry, you never learn to satisfy yourself.

The only way to learn that you can handle your hunger is to prove it to yourself. Wait longer between meals or snacks instead of eating for “future hunger.” If you’re a creature of habit, delay eating at the usual times. So, for instance, if you typically eat breakfast as soon as you wake up, delay eating for an hour and see how it feels.

Another possibility is that you

are

getting hungry, but psychological barriers prevent you from feeling that hunger. For example, you may be afraid that your needs are too big to handle, so you deny them. Or you may feel that you don’t deserve to have your needs met. Or—very common—you may so strongly connect food and weight gain that you don’t allow yourself to feel hungry.

are

getting hungry, but psychological barriers prevent you from feeling that hunger. For example, you may be afraid that your needs are too big to handle, so you deny them. Or you may feel that you don’t deserve to have your needs met. Or—very common—you may so strongly connect food and weight gain that you don’t allow yourself to feel hungry.

One woman in my study noticed that a croissant first thing in the morning led to a nine on the hunger/fullness scale. She realized it was unlikely that she was this full from a single croissant and figured that she

imagined

the croissant would make her fat. Dropping the judgment allowed her to check in with her body. She was able to learn that a single croissant was a comfortably satisfying snack—not overfilling—to get her through a couple of hours. In other words,

giving yourself permission to eat the foods you want when you’re hungry enables you to enjoy your favorite foods in moderation

. She also discovered that it wasn’t sufficiently filling to get her through to her lunch break. The croissant became less appealing as a breakfast on a typical workday because she knew it wouldn’t satisfy her.

imagined

the croissant would make her fat. Dropping the judgment allowed her to check in with her body. She was able to learn that a single croissant was a comfortably satisfying snack—not overfilling—to get her through a couple of hours. In other words,

giving yourself permission to eat the foods you want when you’re hungry enables you to enjoy your favorite foods in moderation

. She also discovered that it wasn’t sufficiently filling to get her through to her lunch break. The croissant became less appealing as a breakfast on a typical workday because she knew it wouldn’t satisfy her.

If this described you, then you were letting yourself get

too

hungry. These symptoms are better described as starvation than hunger. Try to be more attentive to your physical sensations throughout the day, particularly three to four hours after eating.

too

hungry. These symptoms are better described as starvation than hunger. Try to be more attentive to your physical sensations throughout the day, particularly three to four hours after eating.

This is a familiar pattern: getting extremely hungry (1-3 on the Hunger/Fullness scale) followed by overeating (9-10 on the scale). That’s because it’s a response to a biologic phenomenon. When your blood sugar levels drop because you’ve gone too long without food, eating triggers your body to secrete large amounts of insulin so your starved cells can gobble up the energy from your meal. Chemical signals encourage you to eat tremendous amounts to replenish your body, with fullness sensors suppressed.

However, since you’re not using this energy at a faster rate, much of it ends up in storage. Also, you’re likely to be so desperate for quick energy that you crave foods high in sugar (which gets into your bloodstream quickly) and calories (like fat). You are unlikely to be tempted by more wholesome foods. When your blood sugar is low, you may also get moody and mean and feel generally lousy.

Remember all those times you felt so self-righteous because you felt hungry but didn’t eat, picturing the pounds tumbling off? Now you know this strategy backfires. It’s ironic that eating can actually help you maintain a lower weight, often doing a better job than not eating!

Eating should alleviate hunger. If it doesn’t, then you may be eating because of emotional rather than physical hunger, and food isn’t addressing your “real” hunger. Later in the chapter I’ll discuss some strategies to tackle emotional eating.

You might also be “eating without eating,” allowing yourself to become so distracted while eating that you don’t pay attention to fullness signals. Remember what I said earlier: You must be present and taste your food. Eating in front of the television or while driving won’t allow you to be fully sensitive to your food. Nor should you be eating while participating in a stressful meeting at work or while squabbling with your family at home. Food has to satisfy you on numerous levels to fully activate your satiety sensors.

It may also be that you are eating foods that don’t register on your fullness meter and not getting enough of the foods that readily contribute to fullness. Chapter 4 identified some of the culprits, and upcoming chapters will help support you in changing your tastes toward the more nutritious and filling stuff.

This is a very common problem. For many people, overeating is driven by emotional eating. Let’s save that for later in the chapter.

For others, it’s because there’s a time lag between when our stomachs are full and when that fullness message reaches our brains. Too many of us never slow down enough to get that signal until it’s too late. The typical American meal doesn’t even last the twenty minutes it takes an average meal to register. (Some foods might take quite a bit longer, perhaps up to an hour.)

Your past experiences can play an important role in helping you anticipate how the food will affect your satiety level beyond the moment. For instance, history tells me that a typical San Francisco burrito goes down easily, at least in the moment. Thirty minutes later though, I feel lousy—overstuffed and uncomfortable. This teaches me a lesson. Next time I eat a burrito, I stop after finishing three-fourths of it, even if I don’t feel particularly full at the time. A half hour later, I’m perfect!

So check in while you’re eating, and find ways to reduce the amount you’re eating until the fullness signal has a chance to get to your brain. Try out these ideas if they speak to your issues:

•

Be present.

Appreciate all the taste sensations. I like to start with a pre-meal moment of silence to bring my awareness to the table.

•

Choose satisfying foods

. Foods with higher fiber, protein, and water content do a pretty good job of filling up your stomach and more readily activating fullness sensors.

•

Eat slowly

. Put down the fork between bites, sip some water, chew your food well.

•

Take smaller portions initially

(and keep the food away from the table, giving yourself permission to come back). Then, if you’re still hungry, get up and walk over to get more food. This interim provides a time to “check in” with yourself.

•

Leave the dining area

or clear your plate from the table after a meal instead of lingering over the food. This will lessen the “mindless eating.”

Here are some other tricks I’ve found to be helpful. Though they sound very diet-like, remember the context. These tricks are intended to support you in feeling fullness and stopping when you’re satisfied, which gets you to a very different place than trying to reduce your calories.

Eat off smaller plates.

I didn’t think I could be fooled by this, but when my partner changed our dinner plates, we ate smaller portions and were just as satisfied. This suggestion fits with numerous studies finding that when we’re given food in large containers or servings, we’re more likely to eat it all than if we’re given food in smaller containers.

390

391

392

393

I didn’t think I could be fooled by this, but when my partner changed our dinner plates, we ate smaller portions and were just as satisfied. This suggestion fits with numerous studies finding that when we’re given food in large containers or servings, we’re more likely to eat it all than if we’re given food in smaller containers.

390

391

392

393

In one experiment, movie-goers were given free popcorn. Some received medium containers and others large ones.

392

Even though the popcorn was five days old, people ate it anyway, and interestingly, those with the large containers ate an average of 50 percent more than those with the medium containers. More interesting still, those with the large containers said that the container size didn’t affect the amount they ate. But it did. They didn’t eat the popcorn because it tasted good (it was stale!), they ate it because of the external cue: the container size.

392

Even though the popcorn was five days old, people ate it anyway, and interestingly, those with the large containers ate an average of 50 percent more than those with the medium containers. More interesting still, those with the large containers said that the container size didn’t affect the amount they ate. But it did. They didn’t eat the popcorn because it tasted good (it was stale!), they ate it because of the external cue: the container size.

Other books

The Volcano Lover by Susan Sontag

Wild Nights (Hell's Highway MC) by Blakeley Wilde

Dart by Alice Oswald

His Lady Mistress by Elizabeth Rolls

Revealing the Diane Collier Erotic Romance Collection by Diane Collier

The Lady Machinist (Curiosity Chronicles Book 1) by Ava Morgan

Writing on the Wall by Ward, Tracey

The Rocker Who Wants Me (The Rocker... Series) by Terri Anne Browning

Seesaw Girl by Linda Sue Park

Historias de hombres casados by Marcelo Birmajer