Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

The Book of Animal Ignorance (10 page)

W

atching cows placidly munching away in a field it's hard to imagine the fierce creature that so terrified Julius Caesar: âTheir strength and speed are extraordinary; they spare neither man nor wild beast which they have espied ⦠not even when taken very young can they be rendered familiar to men and tamed.' He was wrong, as it turned out. Roman cows were the descendants of these same wild oxen, known as aurochs, which had originated in India and were first domesticated in Mesopotamia, 6,000 years earlier. Although sheep, goats and pigs were already being raised for meat, the domestication of oxen was a turning point: the moment farming became a business. Keeping cows was about more than feeding your immediate family. The word âcattle' originally meant âproperty' â cows were an indicator of wealth.

Cows are fed magnets

to cope with âhardware

disease', the damage

caused by the bits of

wire, staples and nails

which they regularly

swallow. The magnet

sits in the first part of

the stomach and lasts

the cow's lifetime

.

As a potential candidate for domestication,

Bos primigenius

, ticked all the boxes. It was large, ate grass and tasted delicious. You could say the same about bears, hippos and rhinos, but wild oxen herded together rather than ran away or attacked when threatened. And although bulls are fierce, the herd has such a strong hierarchy that most of the animals are used to being docile and obedient. Bears and hippos don't take orders. Nor do they produce gallons of milk, every day, without complaining. Cows quickly became our most reliable machines, converting rough grass into high-protein food and drink.

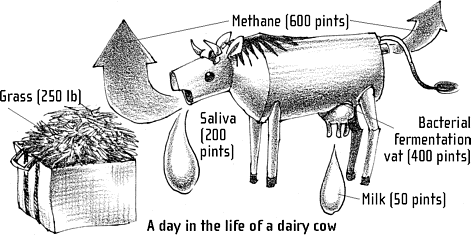

Cow farts are not destroying the world; unfortunately cow burps are. An average cow burps 600 pints of methane a day, and this is responsible for 4 per cent of worldwide greenhouse gas

emissions and a third of the UK's. Livestock farming in general creates 18 per cent of all man-made greenhouse gases â more than all the cars and other forms of transport on earth. Cows produce one pound of methane for every two pounds of meat they yield. Work is under way to produce a methane-reducing pill the size of a man's fist, called a bolus, which would dissolve inside the cow over several months. Even so, cattle farming is costly. To make one pound of beef requires 1,300 square feet of land, six times as much as to produce the equivalent weight in eggs and forty times what it takes to grow a pound of spuds.

MILK AND METHANE MACHINE

On the other hand, cows have many uses beyond the obvious. As well as helping us tame disease through vaccination (

vacca

is Latin for cow), cows have put their whole bodies at our disposal. Pliny the Elder once recommended a concoction of warm bull's gall, leek juice and human breast milk as a cure for earache. Hippolyte Mege-Mouries used sliced cow's udders, beef fat, pig's gastric juices, milk and bicarbonate of soda in his original recipe for margarine. Cows' lungs are used to make anticoagulants, their placentas are an ingredient in many cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, and cow septum (the bit of cartilage which divides the nostrils) is made into a drug for arthritis. Their blood is made into glue, fertiliser and the foam in fire extinguishers. Brake fluid is made from their bones. Sweden even has a cow-powered train that runs on methane harvested from the stewed organs. One cow's worth will fuel a 2-mile journey, excellent news for the Swedish carbon hoofprint.

C

ranes are record-breakers. The crowned cranes (

Balearica regulorum and pavonina

) are direct descendents of the earliest-known birds, whose fossils date back to the early Eocene, over fifty-five million years ago. The sandhill crane (

Grus canadensis

) holds the record for the longest surviving species of bird: a nine-million-year-old leg bone found in Nebraska is indistinguishable from that of a modern sandhill. The oldest recorded bird was a Siberian crane (

Grus leucogeranus

) called Wolf who died in 1988, aged eighty-three, in Wisconsin International Crane Centre. At six feet tall, the Sarus crane (

Grus antigone

) is the tallest flying bird and the Eurasian crane (

Grus grus

) flies higher than any other, reaching 32,000 feet. At that altitude, they are invisible from the ground, but are so loud they can still be heard.

THE CRANE HORN

There are fifteen species of crane and they are found everywhere except South America and Antarctica. Their beauty and elegance have enchanted human beings in every culture. They figure in prehistoric cave paintings, and Homer writes of their âclangorous' sound in the

Iliad

. According to Roman fables, the god Hermes was inspired to invent writing by the letter shapes that flying cranes made in the sky.

Cranes seem almost human. They are sociable, mostly monogamous and spend years raising their

children. They have long memories and complex communication systems, using over ninety physical gestures and sounds.

They are also the avian world's best dancers, using elaborate choreography to develop social skills when young and for courtship when older. In a flock, once one crane starts dancing, all the others join in, bowing, leaping and running and even picking up small objects to toss into the air.

The demoiselle crane

(

Anthropoides virgo

) is

the smallest species,

introduced to France

from Russia in the

eighteenth century. Their

daintiness charmed Marie

Antoinette and she

named them âdemoiselle',

meaning âyoung lady'

.

There is evidence for imitative human crane dances from as early as 7,000

BC

. In ancient China and Japan, among the Ainu of Hokkaido, the shamans of Siberia and the BaTwa pygmies of central Africa, the crane dance is a key ritual. Plutarch even records that Theseus celebrated his defeat of the Minotaur by dancing like a crane.

Cranes have also left their trace in language. Cranberries are named after them, from the similarity between the stamen of the plant and the bird's bill. The word âgeranium' is from

geranos

, Greek for crane: its seedpod resembles the bird's noble head. And âpedigree' comes from the French phrase

pied de gru

, âfoot of a crane', as family trees look a little like birds' feet.

Eight of the fifteen crane species are endangered, two of them critically. In America in 1941, the number of Whooping cranes (

Grus americana

) dwindled to twenty but has since recovered to over 450. The breeding programme involves âisolation rearing', where crane eggs are hatched and reared using hand puppets, humans in crane-costumes and taped calls.

Cranes were once widespread in Britain â almost every county has a Cranwell, Cranbourne, Cranley or a Cranford â but they are now Britain's rarest breeding bird. A tiny colony established itself in Norfolk in the 1980s, the first to do so in 350 years. Its precise location is a closely guarded secret.

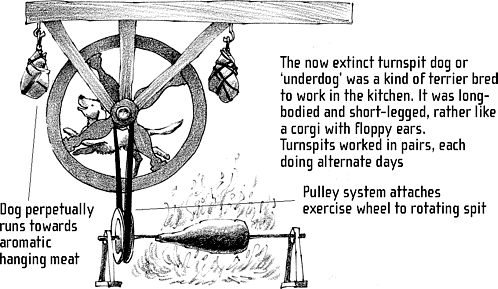

T

he ancestors of dogs were the earliest known carnivores. Dogs evolved from wolves â grey wolves are their closest living relatives â and were first kept by humans between 12,000 and 14,000 years ago. It's not known whether it was a single event that spread, or if it occurred independently in different regions. While some think dogs invited themselves along by scavenging human rubbish dumps and becoming gradually less scared of humans, others think humans adopted wolf pups and that natural selection favoured those with milder temperaments. The famous breeding experiment by Russian scientist Dmitri Belyaev in the 1950s showed it took wild silver foxes only twenty years to transform into tame dogs (see under Fox).

The Fuegians ⦠when

pressed in winter by

hunger, kill and devour

their old women before

they kill their dogs: a

boy, being asked by Mr

Low why they did this,

answered, âDoggies catch

otters, old women no.'

CHARLES DARWIN

Today, there are nearly 400 breeds of domestic dog but all belong to the same species:

Canis familiaris

. In theory, a 2-pound Chihuahua only a couple of inches high can mate with a Great Dane more than 3 feet tall or a 150-pound St Bernard. The vast diversity of dogs is down to humans carefully selecting valuable inherited traits but often encouraging unusual ones such as dwarfism or lack of a tail that, in the wild, might prevent a dog surviving long enough to reproduce. Specialised hunting skills were especially sought after. Springer spaniels have the ability to âspring', or startle, game. The dachshund's sausage-like body enables it to pursue badgers into their burrows (âbadger' is

Dachs

in German). Labrador retrievers were bred to retrieve fishing nets in Newfoundland. There are Harehounds, Elkhounds and Coonhounds; Leopard Dogs, Kangaroo Dogs and Bear Dogs;

there is even a Sheep Poodle. Poodles were originally used for duck hunting: the word comes from the German for âto splash in water'. But dogs are bred for all sorts of reasons. Louis Dobermann, a German night watchman, produced his namesake for watchdog purposes in the late 1800s. Toy varieties, such as the Pekingese, were raised in ancient China as âsleeve dogs' â kept inside the gowns of noblewomen to keep them warm.

A DOG'S LIFE

There's no question about it: unlike cats, dogs are useful. A dog's nose has 220 million olfactory cells, humans a mere five million. A dog's sense of smell is not only hundreds of times better than a human's: it's four times better than the best man-made odour-detecting machines. Dogs can be trained to find almost anything by smell: explosives, drugs, smuggled animals, plants and food, landmines under the ground, drowned bodies under the surface of lakes. They can even smell cancer. Doctors in California have found that both Labradors and Portuguese water dogs can detect lung and breast cancer with greater accuracy than state-of-the-art screening equipment such as mammograms and CT scans. The dogs correctly identified 99 per cent of lung cancer sufferers and 88 per cent of breast cancer patients simply by smelling their breath. Dogs wag their tails when sad as well as when happy. Cheerful dogs wag their tails more to the right side of their rumps. Morose dogs wag to the left. Help them wag to the right: they deserve it.