The Book of Animal Ignorance (6 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

T

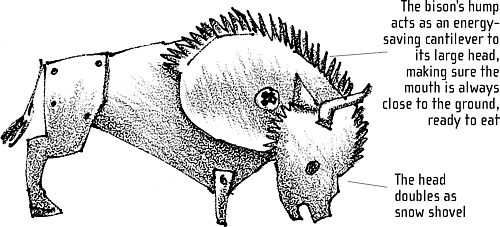

he bison herds of North America's Great Plains formed the greatest mass of land animals in the history of the planet. They could stretch 50 miles long by 20 miles wide. By 1890, there were only 635 bison left.

The American bison (

Bison bison bison

) is commonly called the buffalo, although it is not related to true buffaloes. It migrated from Asia into America 400,000 years ago and is now the biggest North American mammal: adult males weigh a ton, are 10 feet long, and stand 6 feet tall at the humped shoulder.

Bison are the most efficient machines yet developed for eating grass. Their teeth are wide, to maximise the volume of each bite; and long, to stop them wearing out quickly. Forty per cent of their body weight is digestive tract: their fourth stomach chamber holds 600 pints but a mouthful of grass takes up to ninety hours to digest. Bison chew the cud like cows, but extract a third more nutrients.

In medieval

bestiaries, the

European bison

was known as the

âbonnacon' or

âvilde kow', which

defended itself

by spraying a jet

of excrement

over a distance

of 80 yards

.

Since the end of the last ice age, the bison's only predators have been bears, wolves and humans. Many archaeologists now believe that it was hunting by early humans that made them form large herds.

The size of the herds means an amorous male has to stand out. Successful males have evolved bigger heads and more powerful front legs and shoulders, covered in darker woolly hair. Rutting males run full-tilt at one another and clash heads: the sound carries for three-quarters of a mile.

Without bison urine there would have been no prairie: it transformed the fertility of the soil. The more bison, the more grass, the more bison. The fragrant bison grass, used to flavour vodka, thrives on bison urine.

It was the railroad that started the slaughter. The workmen who built railways across the USA in the mid-nineteenth century needed meat for food. At the same time, the British army decided âbuffalo' leather made the best boots. Hunters were offered $2 a hide (called ârobes') or 25 cents for a tongue. A full-time bison-hunter like Wyatt Earp or âBuffalo Bill' Cody could kill a hundred in an hour. Shooting bison for fun from moving trains became a popular pastime.

It was all over by 1890. Only 1 in 5 of the slaughtered bison were put to commercial use, the rest rotted on the ground. The total contribution of the fifty-year âbuffalo trade' to the US economy was $20 million, a paltry 28 cents per animal.

Specicide led to genocide. The indigenous tribes relied on bison for every aspect of their livelihood. The US government encouraged the systematic extermination of the herd as the simplest way of ethnically cleansing the valuable prairie lands.

Today, the North American herd has recovered to 350,000. Most are photographed by tourists or farmed for food. With a third more protein and 90 per cent less fat, bison meat is more nutritious than beef. Cattle and bison hybrids are also bred for eating: they are called âcattalo' and âbeefalo'.

D

espite appearing to be just a mouth surrounded by tentacles, box jellyfish or

cubozoans

(literally âcubed animals') have eyes with lenses, corneas and retinas very similar to our own. Odder still, despite having all this sophisticated equipment, their eyes are permanently out of focus.

This is because a box jelly doesn't have a brain, just a ring of nerves around its mouth. Without central processing power, the blurry vision tells it all it needs to know. How big? Can I eat it? Will it eat me?

The eyes are on four club-like stems on each side of the cube-shaped body. As well as two âsmart' eyes, these stems each have four light-sensitive pits. Again, this is linked to their lack of a brain, which could integrate sensory information. For box jellies, âseeing' a predator and knowing whether it's day or night are separate tasks which require separate sense organs.

Their eyes differentiate them from the rest of the true jellyfish clan (the

scyphozoans

, from the Greek

skyphos

, cup) from which they split at a

very early stage, over 550 million years ago.

Box jellies go to bed at 3 p.m.

and get up at dawn. Once

darkness begins to fall they

lie motionless on the ocean

floor, apparently âsleeping'

.

Sight, however blurred, helps them in other ways. Unlike true jellyfish, which limply float waiting for food to swim towards them, box jellies can swim at speed (6 feet per second in some species) and steer around obstacles. This means they are able to âhunt' prey. There is also evidence that they form mating pairs, with the male using his tentacles to impregnate the female, rather than just spraying eggs and sperm into the sea.

This also helps to explain their other major adaptation. Box jellies are fantastically venomous. One species, the sea wasp (

Chironex fleckeri

), is probably the most poisonous creature on earth. Its sting produces instant excruciating pain accompanied by an intense burning sensation. The venom attacks the nervous system, heart and skin, and death can occur within three minutes. Up to 10,000 people worldwide are stung each year, and there are regular fatalities.

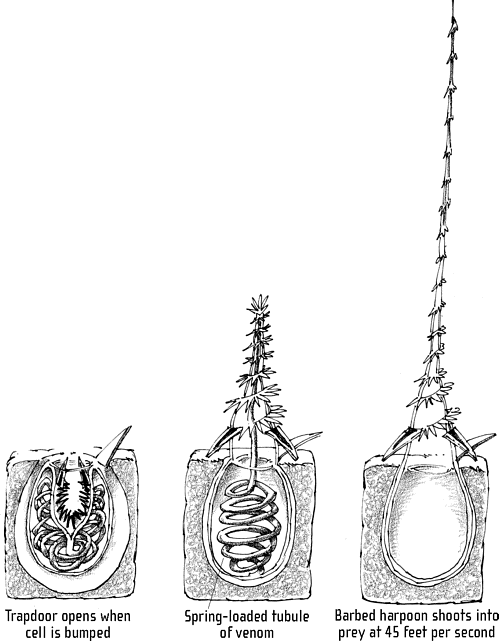

STING CELL

TECHNOLOGY

Another species,

Carukia barnesi

, is almost as toxic. Virtually invisible in water, being transparent and no bigger than a peanut, it is completely covered in stinging cells. Those who survive its sting may suffer âIrukandji syndrome', experiencing intense pain, nausea, vomiting, catastrophically high blood pressure and a feeling of impending doom. It is named after an Aboriginal tribe whose folklore tells of a terrible illness that struck people who went swimming in the sea. The venom causes a massive release of the fight-or-flight hormone noradrenalin, so victims often âpanic' to death.

Why are box jellyfish so toxic and how is this linked to sight? It's a question of scale. Because they can see, they tend to eat things larger than themselves. In order to minimise damage to their own rather delicate tentacles, they need to paralyse their prey immediately. They are only fatal to us because we are so large we blunder into them, exposing ourselves to far more of their sting cells than they usually need to kill their prey.

B

utterflies and moths are the most numerous insect family after beetles, with 200,000 known species. Although butterflies are the more popular, carrying with them associations of sunshine and summer idleness, it's the moths who make up 80 per cent of the

Lepidoptera

(âscale-wings'). One of the reasons for this is temperature: butterflies are basically high-performance sex machines fuelled by flower nectar, Formula One cars to the moth's family saloon. If a butterfly's body temperature falls below 30°C it can't fly and will either die or fall into a torpor. That's why northern countries like Britain are relatively poor in butterfly species â there are only fifty-nine natives and some of them, like the Red Admiral and the Painted Lady, migrate annually, all the way from the Mediterranean. In comparison, continental Europe has over 400 species of butterfly, and tropical Costa Rica (which is the size of Wales) has 560.

Moths are much hardier, and are usually nocturnal. Their bodies are designed to conserve heat rather than absorb it, so they tend to have fatter, fur-covered bodies and rest with their wings spread to the side, rather than folded together above their backs like butterflies. Another point of difference is the antennae: butterflies have a smooth antenna rod with knobs at the end; moths' are feathery. Again, this is partly to do with the day/night split. Moths are much less dependent on sight: they use their antennae as spatial orientation sensors, like our inner ears, to steady themselves as they fly and hover. Cut a moth's antennae off and it will immediately collide with walls and crash to the ground.

Sight is important to butterflies but not quite in the way we imagine. Despite their beautiful appearance, butterflies are extremely near-sighted and cannot judge distance. This is an evolutionary trade-off: their vision may not be sharp, but they can see almost the full 360 degrees, both vertically and horizontally, which is handy for evading predators. The bold wing patterns

have more to do with scaring off hungry birds than attracting mates. What really gets a female butterfly going is the male's iridescent wing scales. These, arranged into the characteristic âeye-spot' patterns, are ridged to reflect UV light â as he flutters his wings at close range he creates a UV strobe effect. Accompanied by heady gusts of pheromone, this literally mesmerises the female.

Unlike most animals, none

of the words for âbutterfly'

in European languages

resemble one another: it is

schmetterling

in German;

papillon

in French;

mariposa

in Spanish;

farfalla

in Italian;

borboleta

in Portuguese

and

vlinder

in Dutch

.

Moths, for obvious reasons, tend to rely more on smell and hearing: a moth can sniff a potential mate 7 miles way. Moths' ears are simple but effective; some species of tiger moth can even tune them to pick up the ultrasonic hunting call of bats and use their wing beats to create a jamming frequency. Both groups have scent scales, which release pheromones to attract females and help their own species recognise them. The Common blue butterfly smells strongly of chocolate; the Goat moth smells of goats.

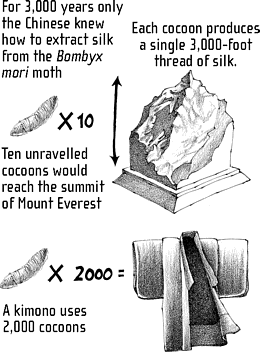

SILKEN SECRET

Many species of moth feed on the tears of larger animals. Tears are a surprisingly nutritious broth of water, salt and protein â like our sweat, which butterflies like to lick. Some, like

Mabra elantophila

, are tiny and hardly trouble the elephants they steal from; others, like

Hemiceratoides

hieroglyphica

from Madagascar, are large and sneaky: they have harpoon-shaped proboscises covered with hooks and barbs which they insert under a bird's eyelids as it sleeps.