The Book of Animal Ignorance (7 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

O

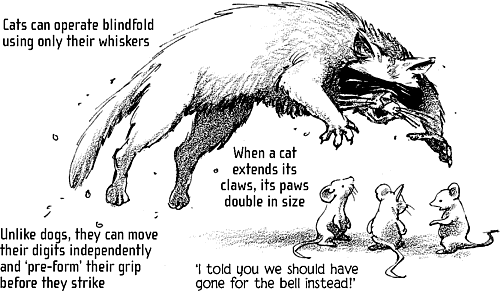

n 18 August 1935, 102 cane toads arrived in Australia from Hawaii. The toads were released on to the sugar cane plantations of northern Queensland to control the ravages of the cane beetle.

Seventy years later, there are now a hundred million cane toads in Australia. They have spread into an area bigger than Britain, France and Spain put together and the front line of their territory expands at a rate of 35 miles per year.

Given the catastrophic decline of the world's amphibious species (see Frog), this may sound like good news. But cane toads aren't good news. They are a catastrophic example of what can happen when humans try to manipulate nature.

Cane toads may yet

prove useful: their

tadpoles inhibit the

growth of mosquito

larvae and the venom

contains serotonin,

which can be used to

treat heart disease,

cancer, mental illness

and allergies

.

Bufo marinus

is very poisonous. Swallowing them as eggs, tadpoles or adults leads to near instant heart failure for most animals. Australian museums display snakes that died so quickly the toad is still in their mouths. Native cats, or quolls, used to eating home-grown frogs, are threatened with extinction. Cane toads can even take out large crocodiles. Their venom is so strong that pet dogs become ill just by drinking water from bowls they have walked through.

In their home territories of Central and South America, cane toad populations are held in check by a combination of competition, disease and predators. In Australia there aren't any other toads, few predators and lots of new things to eat. It's virgin territory and they have risen to the challenge.

They produce four times as many eggs as native Australian frog species, and their tadpoles not only mature more rapidly,

but â being poisonous â don't get eaten. Juveniles and adults will consume anything, from other frogs to unguarded bowls of dog food. The more they eat the bigger they get: some have been recorded at 6 lb â the size of a small dog.

Even more worryingly, their new home seems to be changing them. Their legs are now 25 per cent longer than they were in the 1930s and they can travel five times faster, waiting until the evening to use man-made roads and highways rather than scrabbling through the bush.

Action to control the spread of the toads is widespread, particularly along the border of Western Australia, where the invasion is expected in early 2008. Anti-toad measures once involved driving around so as to run them over in cars. Although cruel hands-on methods like âcane toad golf' still have their advocates, the most effective control is through nocturnal âtoadbuster' squads which raid the waterholes where they gather. A good week's haul might top 40,000 toads. They are then either gassed or deep-frozen to death, and turned into liquid fertiliser called ToadJus.

A biological solution to the plague â genetically engineering a disease to render them sterile â is opposed by many environmental scientists, not least because it was that kind of thinking which caused the problem in the first place.

Despite its undeniable environmental impact, the cane toad has not yet caused any extinctions. Some birds and rodents have even learnt to flip them over and eat them by avoiding the poison glands. Many other species have grown to tolerate them, not least the sugar cane beetle, whose Australian population is, if anything, higher than it was in 1935.

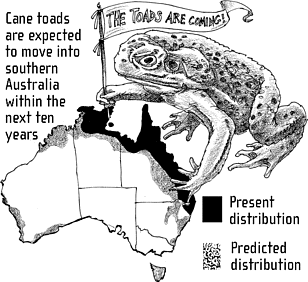

C

apercaillies, also spelt âcapercailzies', are huge woodgrouse as big as turkeys. The name is Gaelic for âforest horse' â although there are no capercaillies (just as there are no snakes or moles) in Ireland. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds gives the collective noun for capercaillies as a âtok'. Interestingly, however, tok is not a word in Gaelic, Danish, Norwegian or Finnish â the local languages of some of the places where these birds are found nor, according to the

Oxford English Dictionary

, is it a word in English either. (Tok is, however, the spelling of âtalk' in pidgin English and a first name in Chinese. It's also a town in Alaska: pronounced toke, it means âpeaceful crossing' in Athabascan Indian. But we digress.)

Despite a

valiant

rearguard

action by the

RSPB, the

capercaillie

heads the list of

British birds

likely to go

extinct by 2015.

If it does, it will

be the only

British bird to

have managed

the feat twice

.

The call of the male capercaillie imitates the sound of dripping water in early spring. It starts off with a similar

pelip-pelip

sound and then picks up speed with

plip-plip-

plip-

itit-

t-

t

, ending with -

klop!

, which sounds like a cork being pulled out of a bottle. The much smaller and less flamboyant females content themselves with a pheasant-like clucking noise. Male capercaillies perform a bizarre courtship ritual called a

lek

(from an Old Norse word meaning âto dance') and they do this at so-called lekking sites. This involves strutting about with tails fanned out and wings held down, making an extraordinary series of noises including strangled gurgling, asthmatic wheezing and, of course, cork-popping. Some experts believe that there are also other sounds, below the range of human hearing, which carry for many miles, broadcasting the male's splendour to

distant females. When the eager females arrive, crouching and making enticing begging noises, spectacular fights break out between the males, resulting in injury or even death. Those males whose grandiose exertions fail to find them a partner can become extremely frustrated and will perform their absurd antics to anything that moves, even cars.

LEK LOUTS ON THE LASH

Capercaillies became extinct in Britain around 1785, owing to over-hunting and forest clearances. In the 1830s, a few birds were imported from Sweden, and by 1960 there were 20,000 of them in Scotland. Today there are only about a thousand: the population has halved in the last five years and the bird is in danger of becoming extinct again. About a third of the deaths are due to the ponderous, low-flying creatures colliding with deer fences and a few of them, no doubt, from giving the come-on to moving hatchbacks.

The longest recorded lifespan of a capercaillie is 9.3 years. A 1992 study of deviant capercaillies in Finland found that about 1 per cent of males behaved abnormally due to testosterone levels up to five times higher than the average. This may be because capercaillies live almost exclusively on a diet of blueberries, a fruit that is supposed to increase the libido and cure erectile dysfunction in humans. Addled by blueberry-fuelled lust, Finnish capercaillies displayed to humans, attacked stuffed male capercaillies and copulated with stuffed females. In 1950, there were three times as many capercaillies in Finland as there are today. This may be because so many of them are stuffed for scientific purposes.

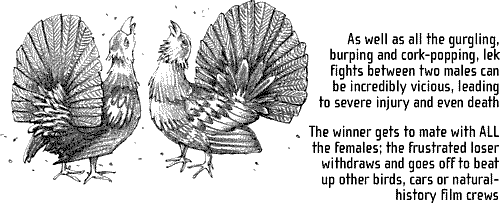

W

hat is a cat? Every child knows. Yet cats, among the most familiar of animals, are ineffably mysterious. What are they for? What do they want? Cats spend 85 per cent of their day doing absolutely nothing. Eating, drinking, killing, crapping and mating take up just 4 per cent of their life. The other 10 per cent is used to get around. Otherwise they are asleep, or just sitting. They say cats were the last animals to be domesticated, by the ancient Egyptians around 3,500 years ago. But it is cats that have domesticated us, in their own time, for their own reasons. Today, only a quarter of American cat âowners' say they deliberately went out to acquire a cat; in 75 per cent of cases, it was the cat that acquired them. And studies have shown that many more people claim to own a cat than there are cats. When your cat disappears for a while it is not, in fact, off on a hunting expedition, it is next door but one having another free meal or asleep on the window-sill with one or another of its many doting âowners'. Cats need to eat the equivalent of five mice a day. A cat given unlimited access to food will only eat a mouse-sized portion at a single meal. Is your cat eating five meals a day? Of course not: it's dining out elsewhere, later.

Most cats carry a

parasite thought to have

long-term, irreversible

effects on the human

brain.

Toxoplasma gondii

may turn men into

grumpy, badly dressed

loners and women into

promiscuous, fun-loving

sex kittens. Half the

British population are

already infected â¦

One of the big selling points of cats is that they are clean animals that carefully cover up their own faeces. Except they don't always â they only do it about half the time. They leave piles of the stuff all round the edges of their territory as a kind of malodorous âKeep Out' sign. The polite word for this is

âscats'. Milk, cat food and central heating are all bad for cats. Milk gives them diarrhoea, cat food rots their gums and central heating causes them to moult all year round. Then they lick off and swallow their fur, which clogs up their digestive system.

There are about 75 million cats in the USA, which are responsible for the deaths of a billion birds and five billion rodents every year. Right up until the seventeeth century it amused people to stuff wicker effigies of the Pope with live cats and then burn the lot. This produced sound effects that pleased Puritans but not cats: they have exceptionally sensitive hearing and can even hear bats.

Research has proved what every cat owner knows: apart from human beings, cats have a wider range of personalities than any other creature on the planet. And yes, they are intelligent. Very. When they can be bothered. There are numerous well-documented stories of cats abandoned by their owners tracing them to locations hundreds of miles from home. Can cats map-read? Maybe. They can certainly tell the time, as recent experiments have shown. The ancient Egyptians worshipped cats as gods: killing a cat, whether deliberately or not, was a capital offence. When a cat died, its owner was expected to shave off his eyebrows. Whose idea was that? A cat's, of course. Cats don't have eyebrows.

ONE BLIND CAT