The Book of Animal Ignorance (9 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

N

obody really understands how they do it, but some species of cicada match their yearly life-cycles to large prime numbers, that is, numbers that can only be divided by themselves and one: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, etc.

âPrime-number cicadas', or

magicicadas

, from the Greek

magos

meaning âmagician', are only found in the eastern United States and their nymphs spend years below ground feeding on tree roots. They only reappear to mate every thirteen or seventeen years.

The reason for this mathematical precision is to avoid even-numbered (and therefore predictable) breeding cycles, which their predators could match. By ensuring that trillions hatch on a single evening, but at unpredictable times, they literally swamp their predators, who gorge themselves until they can't face any more, without damaging the cicada population. There are thirty different broods, each of which is timed to hatch at a different time. The thirteen- and seventeen-year cycles only coincide once every 221 years.

In their long underground imprisonment, the larvae use their droppings to create waterproof cells, to help protect them from flooding. Even so, an estimated 98 per cent perish before they feel the urge to hatch. Those that do survive slough off their

childhood form and mate furiously. Most are dead within a fortnight, providing a huge nitrogen boost for the forest floor.

CICADA HI-FI

Australian

cicadas include

the Green

Grocer, the

Floury Baker, the

Double Drummer,

the Cherry Nose

and the Bladder

.

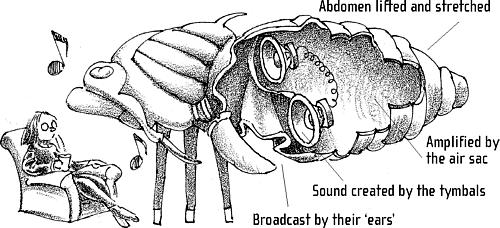

Cicadas are easily the loudest insects, but it is only the males who âsing' and usually only on warm summer days. Some species hit 120 decibels, equivalent to standing in the front row of an AC/DC concert. They can be heard nearly a mile away. Cicadas don't rub their legs like grasshoppers, but make a series of clicks by buckling a pair of membranes, called tymbals, in their abdomens, in the same way we play a wobble board. Their bodies amplify the vibrations.

They often sing in large groups, which makes it impossible for birds to locate individuals, but the main function of the song is to attract a mate (although some have a âprotest song' which they use if you prod them). Each species has its own distinctive set of calls, which the females' ears tune into.

The nineteenth-century French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre tried to demonstrate that cicadas were deaf by firing a cannon towards a tree full of them. Their song didn't change, but not because they were deaf. The sound of the cannon was meaningless to them: you can't mate with heavy artillery.

Because of their apparent ability to be âreborn from the ground' cicadas have come to represent resurrection and immortality in many cultures. In Taoism, they are symbols of

tsien

, the soul which leaves the body at death.

In ancient Greece, they were kept as pets. Plato tells a story of how they were once men whose devotion to music was so great that they wasted away, leaving only their music behind. Aristotle, on the other hand, was fond of eating them fried. Cicadas are still eaten across Asia and Africa and in Australia. Native Americans deep fry them and eat them like popcorn. They are surprisingly meaty and taste like asparagus.

A

round 550 million years ago, animal life came in just four varieties: worms, sponges, jellyfish and comb jellies. The worms splintered into many different branches but the sponges and the jellies have changed little.

Early naturalists couldn't decide if they were animals or not, so Linnaeus compromised by grouping them together as

zoophytes

or âanimal plants'. Comb jellies are particularly plant-like to look at and their common names â sea gooseberry, sea walnut, melon jelly â have a distinct fruit & veg flavour. But they are unquestionably animals, and carnivores at that â gobbling up crustaceans, small fish and one another with what looks like single-minded dedication. Yet they have no brain â and no heart, eyes, ears, blood or bones, either. They are just a lot of mouth.

Most comb jellies are spherical or bell-shaped, ranging in size from no wider than a matchstick to longer than a man's arm. 95 per cent of a comb jelly is water; the rest is made of

mesoglea

(âmiddle glue'), a fibrous collagen gel that acts as muscle and skeleton rolled into one. To the casual observer, they look a lot like jellyfish: in fact the two are from completely different phyla and about as closely related to each other as human beings are to starfish.

Comb jellies are one of

the ocean's most

ethereal sights. The

beating of the cilia

diffracts the light,

making the combs look

like eight shimmering

rainbows

.

The comb jelly phylum is called

Ctenophora

(pronounced âteen-o-fora') from the Greek

ktenos

, comb, and

phora

, carry. Unlike jellyfish, which propel themselves by contracting their bodies, ctenophores move by rhythmically beating their eight âcombs' â rows of

many thousands of hair-like

cilia

(Greek for âeyelashes'). Also unlike jellyfish, comb jellies don't sting. Instead, they have long, retractable tentacles covered in

colloblasts

, special cells that exude sticky mucus to trap their prey. They also have anal pores (real jellyfish use their mouths as bottoms) which nestle next to a gravity-sensing organ called a

statocyst

that tells them which way is up. While jellyfish can regenerate a missing tentacle, half a comb jelly regenerates into a whole animal. Comb jellies also have a simpler reproductive system. Most are hermaphrodites, capable of producing eggs and sperm at the same time (up from the gonads, out through the mouth) and â theoretically â of fertilising themselves. They generally just release thousands of eggs and sperm into the water. Their young can breed as soon as they hatch.

Comb jellies are thought to be more numerous than any other creature of their size or larger. They aren't great swimmers and are frequently swept into great, dramatic swarms, which pose a devastating threat to fishermen.

BEROE'S BLIND DATE

The collapse of commercial fishing in the Black Sea in the 1990s has been blamed on an American comb jelly,

Mnemiopsis leidyi

, that arrived as a stowaway in a US ship's ballast tank. Now known as âthe Monster', it can produce 8,000 offspring a day. The Black Sea population weighs over a billion tons, hoovering up all the plankton that once fed the local anchovies. âThe Monster' has also invaded the Caspian, threatening the cavia

r sturgeon.

In 2001, a cannibalistic comb jelly,

Beroë ovata

, was introduced to hunt down and slaughter its beautiful but remorseless relative.

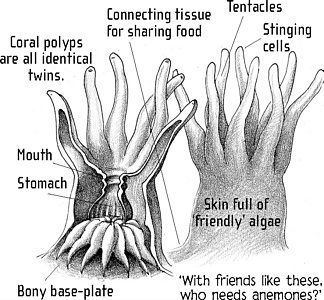

C

orals share their closest family ties with jellyfish. It's hard to imagine two more different-looking animals, but they are both members of the

Cnidaria

phylum (from

knide

, Greek for âstinging nettle'). Coral looks far more like a colourful, baroque relative of the seaweeds, but close examination reveals it as an animal, or rather a host of animals, as each frond is composed of thousands of tiny individual âpolyps', rather like miniature sea anemones (another relative). Each polyp has a fringe of stinging tentacles, a bottom-cum-mouth, and a stomach, just like their cousins. But they do something that the others don't: they build reefs, the rainforests of the ocean.

Coral doesn't age as we

do; most of its cells are

the equivalent of stem

cells in a developing

human embryo, allowing

even a small fragment to

regenerate into a whole

polyp. Some polyps may

be over a century old

.

By sucking in seawater, polyps extract the elements they need to lay down a solid base of calcium carbonate. This base is added to gradually, at about an inch a year, This provides a cup-like shelter for each polyp to hide in and keeps them moving upwards towards the light. Coral polyps âgrow' rock, in the same way humans grow bones. Eventually, as millennia pass, it becomes a reef, an intricate subterranean city where two-thirds of all the oceans' species live. If you gathered all the corals reefs in the world together they would cover an area twice the size of the UK.

Corals don't manage this all by themselves. They have evolved one of the most mutually beneficial partnerships on the planet, with tiny algae called

dinoflagellates

(Greek for âwhirling whips', which describes their method of propulsion), small enough to live, two million to the square inch, in their skin. The coral polyps catch microscopic organisms with their tentacles, and the

waste products (mostly carbon dioxide) feed the on-board algae. In return, the algae give the polyps their striking colours, and produce most of their energy by photosynthesising sunlight. This is why you find most corals in shallow, clean, sunlit water. The algae even make a sunscreen that protects the polyps, allowing them to keep working all day. And it is hard work: reef-building corals use up proportionately two and a half times as much energy as a resting human.

Coral's relationship with algae is not without its tensions. If the algae can get food more easily elsewhere, as happens when the reef silts up or becomes too warm or polluted, they will leave, âbleaching' the polyps white and condemning them to death. In the record-breaking heat of 1997 and 1998, a sixth of the world's coral reefs âbleached'. It is now estimated that a tenth of all the world's reefs are dead, and if the carbon levels in the oceans continue to rise the rest will follow by 2030. Coral reefs are on the front line in the war against global warming.

A FAMILY GROUP

Indirectly, coral helped Charles Darwin refine his ideas about evolution. Although he had no idea about the symbiotic relationship with algae, his first scientific book after returning from the voyage on the

Beagle

, published in 1842, was an account of the formation of coral reefs. He theorised (correctly) that atolls were formed by undersea volcanoes slowly sinking under the surface of the ocean, leaving the ring of coral still growing upwards towards the light. The long process of geological change implied by this confirmed his hunch that constant change was at work all over the biological kingdom.