The Book of Animal Ignorance (12 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

W

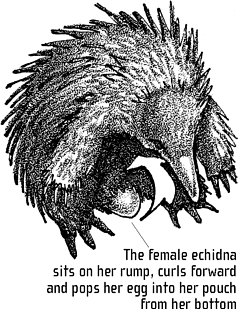

hat has a bird-like beak, spines like a hedgehog, the eggs of a reptile, the pouch of a marsupial, the life span of an elephant and a penis like a four-staved club? Enter the echidna, Australia's almost-anteater. Like anteaters the echidna has a long sticky tongue, powerful front legs and a huge appetite for social insects. But there the similarities end. The echidnas aren't even marsupials, they're monotremes (âone-holed' creatures), so named because, like birds and reptiles, they have a single hole or cloaca for excretion and reproduction. Along with the platypus, the four species of echidnas are thought to be the only descendants of the southern mammals that split from their northern counterparts before the super-continent known as Pangaea began to break apart, 180 million years ago in the Jurassic. This makes them the oldest surviving mammal group.

An echidna's neocortex,

associated with reasoning and

personality in humans,

accounts for half the volume

of its brain, compared to only

a third in the âhigher'

mammals. No one knows what

echidnas use it for

.

The Short-beaked echidna (

Tachyglossus aculeatus

â âthorny fast-tongue') is the most widely distributed mammal in Australia. They are shy, solitary creatures that live in large undefended territories (no one has observed an echidna fight). They have two predator-escape strategies: the spiky ball and the sinking ship (echidnas can dig straight down until only their spines are showing). They have the coldest blood temperature of any mammals, and can conserve energy by dropping their body temperature to 4? C and taking only one breath every three minutes. To warm up, they can lie flat like a spiny rug in the sunshine. To cool down, it is thought that their spines dissipate heat like an elephant's ears. They can live for fifty years.

THE EGG &

POUCH TRICK

Mating takes place in the winter when a group of males form a slow-moving âlove train' behind a pheromone-emitting female. This shuffling procession can last for more than a month. As soon as she's ready, the female clings to a tree trunk with her forelimbs while the males dig a 10-inch deep, doughnut-shaped trench around the tree. They then compete for mating honours, gently pushing each other around with their heads. The winner lies on his side in the trench partly underneath the female and, unsheathing his curiously configured member, mates, pressing his belly against hers. A single grape-sized egg follows three weeks later, hatching a wriggling, bean-like âpuggle'. After eight weeks of rapid growth, the puggle is transferred to a burrow, just as the spines start to show.

As for the other species, there can be few animals more mysterious than the Long-beaked echidna (

Zaglossus bruijni

â âde Bruijn's long-tongue') of New Guinea. Here's all we know: its body and nose are twice the size of its cousin's; it's furrier; it mainly eats earthworms speared with special spines on its tongue and then sucked up like spaghetti; it's nocturnal; it snuffles a lot. That's it: everything else is conjecture. We think there are three subspecies: one (rather sweetly named after Sir David Attenborough) is restricted to a single (dead) specimen, found in 1961. The other two are endearing, inquisitive creatures that look like four-legged kiwis and tame easily. This has made them easy to hunt, and since the arrival of Europeans, the taboo against killing a once sacred animal has disintegrated. Papuan tribesmen track them with dogs and serve them roasted as a delicacy. How many are left? We have no idea â¦

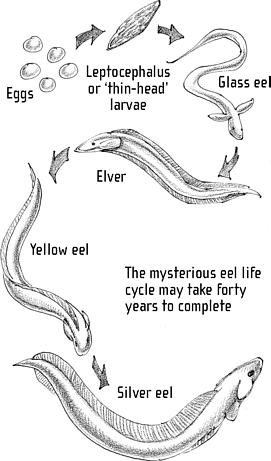

N

obody knows where the word eel comes from. Until the 1920s, nobody knew where eels themselves came from. Aristotle insisted they arose spontaneously from rotting seaweed. Pliny the Elder thought they rubbed against rocks and that the shreds of their skin came to life. Other imaginative suggestions included the dew of May mornings, the gills of fish, and horsehairs falling into the water. The astonishing life-cycle of the eel was first revealed to the world by the Danish oceanographer Johannes Schmidt (1877â 1933) who, in 1905, was commissioned by his government to locate their spawning grounds. Given one small ship, he set off to trawl the oceans of the world. It took him sixteen years.

Eels are one of very few species

of fish that can swim

backwards. Their thick coating

of mucus means they can also

travel on land as well as in

water. They make their way into

fields and gardens to snack on

young peas and beans

.

THE EEL REEL

It seems all European and American freshwater eels (

Anguilla

anguilla

) are born as saltwater fish in the Sargasso Sea, a strangely calm area of the North Atlantic around Bermuda, two million square miles in extent and clogged with Sargassum weed. This is kept afloat by berry-like bladders: hence the name from

sargaço

, an old Portuguese word for âgrape'. From here, the eel larvae are carried by the Gulf Stream 3,000 miles across the Atlantic to Europe, where, on entering the mouths of rivers, they miraculously transform into freshwater creatures. They don't aim at a particular river: they hit the coast in a broad band and swim up whichever one they encounter â so rivers with wide west-facing estuaries like the Severn get lots of them. They will go to any lengths to reach their goal, piling up their bodies by the tens of thousands to climb over obstacles. Once there, the eels live contentedly in

rivers until they reach maturity. When this happens (between the ages of six and forty) they prepare to swim back to the Sargasso Sea again. They change dramatically. Backs turn darker; bellies turn silver. They toughen up, storing fat, which they'll need for the journey. Eyes enlarge, heads become pointed, nostrils dilate, the salt content in their bodies reduces and their sex organs swell. Their gas bladder also changes to allow them to withstand pressures of a ton per square inch.

Once back in the Sargasso, the females spawn and the males fertilise the eggs, after which they all die of exhaustion. Or so it is believed. Nowadays, âeverybody knows' that eels are born in the Sargasso Sea but this has never been proved. No one has ever seen an eel spawn or seen one die there. Careful scientists prefer to call the Sargasso Sea the eel's âpresumed' breeding ground. Young eels have been found there, but neither live adults nor their eggs. Not one eel has ever been bred in captivity. When you catch an eel, its reproductive system shuts down completely, as if deliberately keeping the secret. Sigmund Freud was determined to find the answer. He worked in Trieste cutting up hundreds of eels to see how their sexual organs worked. When he had finished, he published a thesis in which he concluded that all of his research was a waste of time. He was no nearer to understanding eels than when he first started.

E

lephants are the largest living land animals and size is both the secret of their success and the reason they look the way they do. Elephants grew big to compete with the waves of antelopes and other ruminants munching their way across the grassy plains. To eat the coarse, woody vegetation the ruminants couldn't manage required a big digestive tract and long legs. So they got bigger and by about two million years ago had spread all over the planet except Australasia and Antarctica.

Size brought its challenges. Overheating is a problem for large mammals: the elephant's ears evolved to stop it boiling to death. Unlike the thick skin that covers most of their bodies, the skin on their ears is paper-thin. Each ear is the size of a single-bed sheet and when it flaps, the airflow reduces blood temperature by up to 5°C. The skein of blood vessels acts like the grill in a car's radiator. The pattern they make is unique to each elephant and can be used to identify them, like human fingerprints.

The other challenge is drinking, as kneeling down makes even a large animal vulnerable to attack. Elephants evolved the perfect solution, a 7-foot, 28-stone nose that contains a hundred times more muscles than we have in our entire bodies. Not only can a trunk suck up 8 pints of water, it also functions as an arm, hand, snorkel and weapon. It is powerful enough to kill a lion with a single blow, yet the finger-like lobes at the end can pick up a grain of rice.

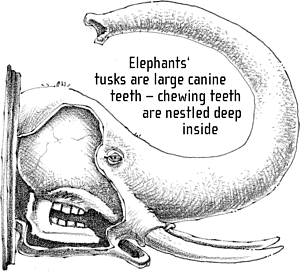

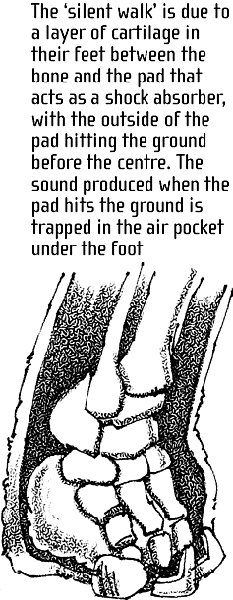

Despite weighing over 3 tons, elephants still walk on tiptoe, like most mammals, but they are the only mammals with four forward-facing knees, needed to give them extra leverage when standing up. They can't run or jump (to ârun' all feet must be off the ground at once) but they can walk silently, reaching a top speed of 15 mph. They also use their feet to hear, picking up the very low frequency calls (inaudible to humans) of other elephants from as far away as 6 miles. Males and females can't understand each other's calls, and the female vocabulary is much larger.

Elephants are large-brained and clever: along with dolphins and some primates, they are the only animals that can recognise themselves in a mirror. They spend twelve years as calves and their development involves a lot of learnt behaviour â a young elephant has to be shown how to use its trunk. They have elaborate mourning practices and often visit and fondle the bones and tusks of the dead. The oldest elephant ever recorded was eighty years old, but most live for about fifty years. With few predators (other than man), the default elephant death is starvation caused by their teeth wearing out.

The closest living relatives of the elephants are the sea cows, and then the hyraxes, furry creatures that look like large hamsters. The common ancestor of all three was a giant hyrax, Africa's primary herbivore until the ruminants arrived and set one branch of the family on the way to sprouting trunks.

An elephant's gait

is a bit like

Groucho Marx's:

crouching slightly

seems to help

them to move their

bodies more

smoothly

.