The Book of Animal Ignorance (26 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

B

efore we dismiss pigeons as ârats with wings', consider why the rock dove,

Columba

livia

, which originally appeared in Australasia twenty-five million years ago and which still lives happily on some sea cliffs, made such a complete transition to city life. Why are there so many? Cities are full of artificial cliffs (we call them âtall buildings') and people throwing out stale bread and dropping half-eaten kebabs. Unfortunately, food stimulates breeding, with the result that we now have non-stop breeding pigeons, with some females laying six times a year, and raising as many as twelve squabs each.

Rock doves were first domesticated by the ancient Egyptians for food and message-carrying. Urban populations were established by escaped domestic birds and they've never looked back. The estimate for the damage caused by pigeon droppings in the US alone is $1.1 billion. But we shouldn't overreact: there is little evidence to suggest that pigeons pose a serious health risk to humans. The worst disease associated with them is psittacosis, or parrot fever. New York City, home to 100,000 pigeons, records one case per year and pigeons have proved particularly resistant to the H5N1 avian flu virus.

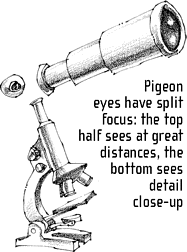

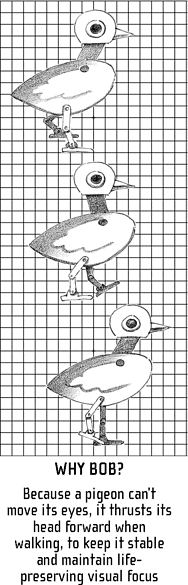

Rather we should marvel at their gifts. To stay alive in the wild a pigeon needs to keep its eyes open for predators. Their position on either side of its head gives it a field of view approaching 340? and in order to fly at

speed it has to process visual information three times faster than a human. If a pigeon watched a feature film, twenty-four frames per second would appear to it like a slide presentation. They would need at least seventy-five frames per second to create the illusion of movement on screen (this is why pigeons seem to leave it until the very last second to fly out of the way of an oncoming car: it appears much less fast to them).

According to the

seventeenth-century

natural historian John

Aubrey, the traditional

remedy for the bite of

an adder was to apply

the âfundament of a

pigeon' to the wound to

suck out the poison

.

The US navy has tried to exploit their keen-sightedness by training them to spot sailors lost at sea: they can pick out a far-away orange life-raft much better than a human. They have also been put to work inspecting drug capsules for defects. Pigeon vision is smart as well as sharp: they can tell tthe difference between Cubist works by Picasso and Impressionist canvases by Monet and are even able to tell when the Monets are hung upside down. They also navigate with great precision, using a combination of odour trails, the sun's position, the earth's magnetic field and, as they get closer to home, visual landmarks like road systems.

Pigeons mate for life; widowed birds accept new mates very slowly. They are also model parents: the male and female take turns to incubate eggs, and care for their young in the nest. Both produce âpigeon milk' in their crops. It isn't real milk â there is no lactose in it â but looks like cottage cheese and is fed to the chicks for their first ten days. That's why you don't see baby pigeons: they grow so quickly that by the time they leave the nest, they are almost the size of an adult.

W

hen George Shaw made the first written description of the platypus (

Ornithorhynchus anatinus

) in 1799, he first carefully checked the specimen he had been sent from Australia for signs of stitching. Even so, many of his naturalist colleagues continued to believe it was a hoax: a duck's bill sewn on to the body of a small beaver. It took thirty years for it to be accepted as a mammal â the lack of nipples made it difficult to locate the mammary glands under its stomach fur. But it wasn't until 1884 that the real bombshell fell. A Scottish embryologist called W. H. Caldwell finally uncovered a platypus nest and revealed the astonishing news that here was a mammal that laid eggs (the Aborigines had been saying this for years, but no one had listened). The platypus has remained notorious ever since, ridiculed as evolution's little joke.

A popular nineteenth-century view, still held in some quarters, describes the platypus as a crude early prototype of the mammal, subsequently abandoned. It is true that together with the four species of egg-laying echidnas it sits in the monotreme (âone-holed') order, the oldest surviving group of mammals. But to disparage it as a primitive, âhalfway house' between reptiles and mammals makes no more sense than calling a craftsman who builds wooden furniture from scratch more âprimitive' than someone who puts up flat-pack shelving from Ikea. The platypus is a perfect example of a creature that has, in isolation, adapted itself to exploit a rich habitat. Think of it as Australia's otter, an opportunistic carnivore, guzzling down freshwater crayfish, shrimps, fish and tadpoles with little competition. It has kept some of the âreptilian' features, like egg-laying and a lizard-like way of walking, because there was no pressure to change them. But it has also evolved other new adaptations of astonishing sophistication.

In 1943 Churchill asked

the Australian prime

minister to send a live

platypus to cheer him

up. Sadly, âWinston'

died en route but

Churchill had him

stuffed and kept him

on his desk for the rest

of the war

.

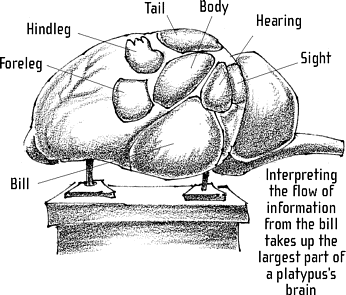

The most ingenious of these is the âduck's bill' itself. The platypus is a nocturnal creature, feeding at night and dozing in its burrow or âwedging' under a rock or tree root by day. Hunting at night under water poses a challenge, as smell and sight are useless. The platypus's solution â unique among mammals â is to borrow a trick from fish and turn its ânose' into an electrical probe. The bill is covered in 40,000 sensors that can pick up the tiniest electrical fields generated by muscle impulses in its prey. As well as that, it also has 60,000 motion sensors, allowing it to act as both eye and hand, with mechanical and electrical information combining to create a vivid picture of its dark underwater world.

BILL BRAINED

It has also come up with its own dual-purpose propulsion system. As with beavers, the tail is used to store fat, but when the platypus swims, it acts as a rudder not a propeller. All the power comes from the large webbed front limbs. On land, these skin flaps fold away so it can use its front claws to burrow. Though as fast as an otter in water, the platypus rivals the mole as a digger of tunnels on land, which is why it earned it the name âwatermole' among the early settlers. Duck, mole, otter? Perhaps it's the mark of a true original that it can only be described in terms borrowed from something else.

â

P

orcupine' literally means âspiny pig', although they are rodents and not remotely related to either pigs or hedgehogs. There are twenty-five species, split between Old and New Worlds. All are spiny, but some New World species can climb trees and swing from branches using their tails like spider monkeys. In Europe, they are native only to Italy and Greece but have been known in Britain since 1110, when Henry I was given one as a pet.

Never rub bottoms

with a porcupine.

GHANAIAN PROVERB

The inevitable question that crops up with porcupines concerns their love life. As it turns out, avoiding the spines is the least remarkable detail. Porcupine sex often begins with both male and female walking on their hind legs astride sticks, which they use to stimulate their genitals. Once whipped up into a frenzy they stand belly to belly. With his now erect penis, the male soaks the female from head to toe with urine (streams reaching more than 6 feet have been recorded) and begins to make a loud squeaking, similar to the âlove song' of mice. The female turns her back on him and arches her tail over her back. There aren't any quills underneath it and he has no quills on his belly. The actual mating lasts only a minute but the male porcupine has a secret weapon. As with other rodents, his penis points backwards in its sheath, unfolds like a penknife when erect, and has bristly barbs on its tip. But the porcupine also has two pointy ânails' on the underside that aren't found in any other animal. Whether they are for âlatching on', or giving added pleasure, we don't know.

The outcome, after a long gestation, is called a porcupette. Unusually for a rodent, there is only one. It is born with its eyes wide open and a fully developed set of quills, which are ready to use within twenty minutes. Indian porcupines (

Hystrix indica

) seem quite happy with the set-up.

They mate for life, and are the only rodents that copulate even when there is no possibility of conception, a helpful adaptation for the monogamous.

The scientific name for the Old World porcupines comes from the Greek word for them,

Hystrix

, while the North American porcupine's Latin name,

Erethizon dorsatum

, translates literally as âI have a back that provokes'. Despite Pliny the Elder's assertions, they can't fire their quills, but tiny erector muscles in the skin do make them stand up. Then they lunge backwards, swiping their tails violently. Even tigers run scared.

There can be over 30,000 quills on a single animal, and they grow replacements. The quills are covered in backward-pointing scales. These help the quill to work slowly into flesh where it can be fatal if it hits a vital organ. To remove a quill, cut off the end sticking out first to equalise air pressure inside the wound.

Native Americans used porcupine quills to create sacred designs. The Arapaho no longer practise the craft because the last of the seven women who fully understood the designs died in the 1930s. To attempt quillwork without the proper ritual knowledge is considered dangerous.

African porcupines are attracted by loud drumming and can be taught to shuffle in time to the beat. Porcupine is still eaten there and in Italy, where they have a reputation for yielding even crispier crackling than pork.