The Book of Animal Ignorance (29 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

T

he sea cow family, or sirenians, contains the dugong (

Dugong dugon

) and three species of manatee (

Trichechus

, after their âhairy' snouts). As their common name suggests, these large, docile creatures are the only aquatic mammals that live on plants. Although they look like grey tuskless walruses, their closest relatives aren't cows, walruses or whales but another large herbivore, the elephant.

Manatees often

congregate near

power plants,

because of the

warm water. In

return, they keep

the surrounding

channels clear of

weeds

.

Sea cows have a very laid-back life. They paddle around in warm tropical seas, with little competition for food and no natural predators. As a result, they have a very leisurely metabolism. The largest adults weigh over a ton and spend eight hours a day slowly chomping through six straw bales' worth of aquatic plants, which take a week or more to digest. Life is slow enough for algae and barnacles to grow on their skin. Some dugongs have been recorded as living into their seventies, and they only manage one calf every three to seven years.

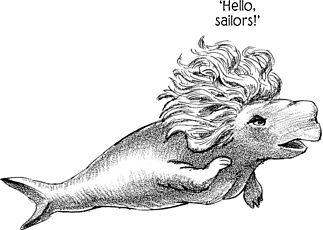

When they aren't eating or sleeping, sea cows come together regularly to âcavort'. These sessions of nuzzling, bumping, kissing and mutual masturbation are often male-on-male, but can involve up to four individuals of either sex and last for several hours. The normally silent manatees make a sequence of distinctive âsnort-chirps' as they cavort, though no one knows how (even if we can guess at why). This pleasure-filled life, combined with the female dugong's large and elaborate clitoris and pendulous âbreasts', has contributed significantly to the mermaid myth. In the Solomon Islands, âdugong' is the slang term for prostitute.

Dugongs and manatees also have a reputation for stupidity and their brains are, proportionally, small and smooth, roughly the equivalent of our brains shrunk to the size of a plum. In their defence, their brains seem well up to the job and some have even been trained to recognise colours and patterns in return for food.

More significantly, low metabolism and the absence of stress help make them impervious to the diseases which afflict other mammals, propelling them to the forefront of research into cancer and HIV.

This may also explain why they have six neck vertebrae rather than seven. In mammals, the genes that specify the number of vertebrae also control the nervous system and cell growth. Changes in this genetic data can cause cancer, so natural selection has tended to leave them alone. However, in a low-metabolism mammal like a sea cow the risk of cancer is greatly reduced. Over time, this might have allowed the genes to risk variation. Interestingly, the only other mammal with an irregular number of neck vertebrae is the sloth, another noted slacker.

âManatee' comes via

Spanish from a Carib

word meaning âbreast',

while âdugong' derives

from Malay âduyung'

meaning âlady of the

sea'. Like elephants,

they have two teats

under their forelimbs,

causing sailors to

mistake them for

mermaids

.

But there is a downside. Slow, inquisitive and delicious (roast dugong tastes like veal) is a bad combination when faced with

Homo sapiens

. All four sea cow species are now endangered, as result of hunting, pollution and damage from propellers and fishing nets. The historical precedent is grim. Their relative, the Steller's Sea Cow, three times the size of the largest manatee, was hunted to extinction in the twenty-seven years after its discovery in 1741.

S

ea cucumbers have been trundling along the bottom of all the planet's oceans for 500 million years. They do an essential job as marine binmen, processing over 90 per cent of all the dead plant and animal material that settles on the sea floor. Many of them do look like knobbly cucumbers. Their family name,

Holothuridae

, is thought by some to mean âcompletely disgusting'. The Romans called them

phallus marinus

, presumably because of their shape, and even Darwin dismissed them as âslimy and disgusting'. One Mexican species,

Holothuria

mexicana

, is known as the Donkey dung: a perfectly accurate, if unflattering, description.

THE

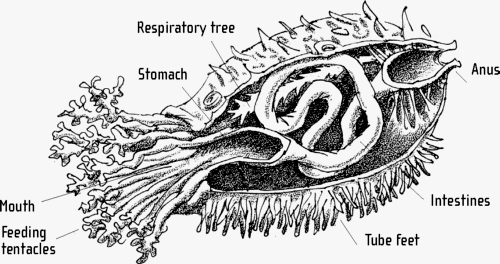

INNER

CUKE

Despite their shape, the 1,100 species of sea cucumber are close relatives of the starfish and the sea urchin, sharing the same fivefold body symmetry and, like them, moving on tube feet driven by piped seawater. But âcukes', as marine biologists call them, have other tricks. They breathe through their bottoms, drawing in water through their anus to fill a respiratory âtree' and then expelling it along with any digestive waste that might be lurking. Single hole: two functions. This fact has been exploited by the tiny eel-like pearlfish. They wait until the cucumber's

anus opens in the morning and then sneak inside, spending a leisurely day swimming around the intestines, before emerging again to feed at night. Some even knock to gain entry. Juvenile pearlfish are less welcome as they have a habit of gnawing on the cucumber's gonads.

Sea cucumber was

Australia's first food

export. Aborigines on

the northern coast

traded them with

Indonesian fisherman

from as early as the

sixteenth century

.

Cukes are nocturnal and need to fill sixteenth century. their guts at least twice a night, so life mostly alternates between sand-vacuuming and resting. If they are stressed or threatened, they have an impressive array of escape strategies. Their bodies are made from a connective tissue called âcatch collagen', which gives them an almost miraculous ability to change from solid to fluid. This enables them to âpour' into the tiniest crevices and then stiffen again so they can't be extracted. Some species can blow themselves up to the size of a football. Others expel water to make themselves look like pebbles, but the ultimate cucumber party-trick is to blow their guts out of their bottom and flood the surrounding water with a toxic soup. Known as a âcuke nuke', this can wipe out all the fish in a small aquarium, as well as the cucumber itself.

Some species have a more sophisticated version, expelling fine sticky threads, known as Cuvierian tubules, out of their backsides. These form an astonishingly sticky net which can tie up a hungry crab for hours. On the Pacific island of Palau, islanders milk cucumbers of their tubules and bind their feet with them to make improvised reef shoes. They are also used as a sterile dressing for wounds. Amazingly, a cucumber that has been harvested of its guts, gonads or tubules can grow them back within a couple of months.

Dried sea cucumber, known as

trepang

or

bêche-

de-

mer

, is eaten as a delicacy all over Asia, and has a reputation as both an aphrodisiac and a painkiller. The global sea cucumber market has grown to £2.3 billion and this is putting pressure on some species, leading to the establishment of cucumber farms and sea âranches'.

D

on't be fooled by their cute looks: the seals' closest relatives are bears and they can be every bit as vicious. One of the ways you can tell if a Leopard seal (

Hydrurga leptonyx

) is in the area is an empty penguin skin floating on the water. They violently shake the hapless bird from side to side to remove its coat and then gulp down the naked corpse. They are almost as bad with their loved ones. The male Southern elephant seal (

Mirounga leonina

), six times larger than his partner, occasionally gets carried away during copulation and accidentally crushes her skull between his massive jaws. And when female Hawaiian monk seals (

Monachus schauinslandi

) come into heat they risk being âmobbed', which is the polite scientific term for being battered to death by a gang of amorous males. In order to save the species from extinction, males are now being put on libido-suppressing drugs.

âSelkies', the legendary

Scottish seal women who

leave their skins behind and

are tricked into marriage by

humans, may be a dim folk

memory of visits by shaman

from Lapland, who dressed in

skins and used healing magic.

âSeal' is a Saami word

.

With elephant seals, and their close relatives, the sea lions, this male aggression is also backed by huge size. The bigger and more aggressive the male, the bigger his bit of breeding beach and the higher the number of females he gets to service. A single male might have up to fifty females in his harem, but some harems grow as large as a thousand, serviced by just thirty males, with the top five â the âbeachmasters' â getting most of the action.

Much of the inter-male violence is just noise â loud gargling and slaps â but when fights do break out they can be bloody for both the participants and innocent bystanders. The females don't help: they make such a racket during mating that every male in

the area makes a beeline towards them. In the resulting melee, pups get separated from their mothers, and are crushed or flung out of the way. Some colonies lose two-thirds of the pups in a single season in this way. It is one of the reasons seals' milk has the highest fat content of any mammal's: to ensure the pups grow quickly. The milk is more of a pudding; at 60 per cent fat it's twice as rich as whipping cream. Unsurprisingly, pups put on several pounds a day and are weaned within a few weeks.

It is in the sea that the seal's strength and aggression really sets it apart. A seal hunting in water is twice as efficient as a lion on land. Elephant seals can dive for two hours at a time and reach depths of 5,000 feet. They expel all the air from their lungs to avoid the risk of âthe bends' and survive on the oxygen absorbed in their blood. Their bodies hold twice as much blood as most mammals and, when diving, their heart rate plummets from ninety to just four beats a minute. To help them sink faster, some will even swallow stones.

Better still, a seal's eyes don't go blurry underwater. In other mammals, this blur is caused by the outer lens (cornea) being rendered useless by the water, like a transparent glass marble which disappears when you drop it in the bath. Seals overcome this through a huge spherical inner lens to focus the image, and an extremely adjustable iris to control the light. This not only gives them their big-eyed charm, it also means they can hunt in bright sunlight and the gloomy ocean depths.

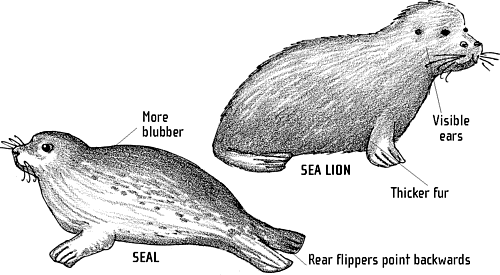

HOW TO TELL A SEAL

FROM A SEA LION