The Book of Animal Ignorance (28 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

O

utside the polar ice-caps, the only place in the world where you won't find any brown rats (

Rattus norvegicus

) is the province of Alberta in Canada. From its home base in Mongolia, the brown rat followed the spread of human cities across the steppes, finally swimming the Volga into western Europe in 1727. From there it travelled the world on ships, scurrying ashore at every port and eventually reaching Alberta's eastern border in 1942. The Albertans decided to fight and set up a 400-mile-long buffer zone that is still patrolled by rat vigilantes. Alberta is cold and human habitation is sparse, so they may just hang on. For the rest of us, the battle was lost before it began. In the USA there are an estimated 150 million brown rats; in the UK, they now outnumber people.

Some people say

that you are never

more than 6 feet

away from a rat but

actually I believe

the distance is

more likely to be

about 70 feet.

TONY STEPHENS,

Rentokil

Here's the problem. A rat can swim for seventy-two hours non-stop. It can jump down 50 feet without injury. It can squeeze through a half-inch gap, leap 3 feet, climb vertical surfaces and walk along ropes. It can survive longer than a camel without water. It will eat anything that's edible and lots of thing that aren't (lead sheeting, soft concrete, brick, wood and aluminium). It reaches sexual maturity at three months. Rats have sex up to twenty times a day, and are extremely promiscuous: an on-heat female can have sex over 500 times with a barnload of different males and produce twelve litters of twenty-two young each year. In short, rats are very, very hard to get rid of.

Which would be fine if we could just grow to love them. That's the next problem. Brown rats consume about a fifth of the food produced in the world each year. They carry over seventy extremely infectious and unpleasant diseases: bubonic

plague, of course, which has killed a billion, but also cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, Weil's disease, salmonella, crypto-sporidiosis, E. coli, foot-and-mouth, SARS and eight species of parasitic worm. A quarter of all electrical cable faults are due to rats' ever-growing teeth, as are most âunexplained' domestic fires. Like mice, their communication system involves near-constant urination â rats piss on one another to show affection, attraction, dominance and submission, and on food just to show it's edible. Oh, and they carry a lively subculture of fleas, mites and lice everywhere they go, which is everywhere we go. It is very, very hard to love the brown rat.

Not that there isn't plenty to admire. They are intelligent and resourceful, they learn fast and have excellent memories. Their sense of smell is of such sensitivity and refinement that it makes you wonder why they waste it all on water sports. They seem to have a sense of fun and an ultrasound giggle which they use when being tickled, during sex or when a rat they fancy sprays on them. They make very good pets, and despite the evidence to the contrary, spend almost half their lives keeping themselves clean.

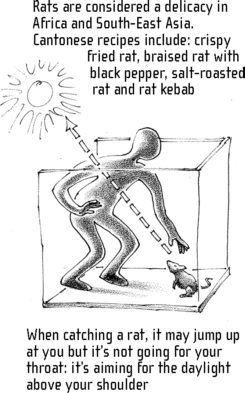

FIRST CATCH YOUR RATâ¦

But it doesn't matter what black pepper, salt-roasted we think. Thanks to our rat and rat kebab wasteful habits, rats are unbeatable evolutionary winners. Maybe in time the brown rat will itself be driven out, as it drove out the black rat (

Rattus rattus

), which in the UK at least could now apply for endangered species status. But whatever takes its place, you can rest assured that it will only be a bigger, better, smarter rat.

T

he 500 species of amphibious salamanders come in every shape and size, from the giant Chinese (

Andrias davidianus

) which can be 6 feet long and weigh 5 stones, to the tiny

Thorius

, which is the smallest land-living vertebrate at half an inch long, and the smallest animal of any kind with proper eyes.

The axolotl (

Ambystoma mexicanum

) is the most celebrated. Only found in a single lake in Mexico, at a certain point in their evolution they just stopped developing into adults, and now spend almost their whole life in the water as large tadpoles. Why they took this backward step isn't clear. It might have been provoked by the land habitat around their lake becoming more hostile, but it doesn't seem to bother other salamander species that live there. Occasionally, they do grow up into something resembling an adult tiger salamander and this can be artificially stimulated by injecting them with hormones. 99 per cent of the world's axolotls are now kept in captivity, most of them descended from the six specimens that arrived in French zoologist, Auguste

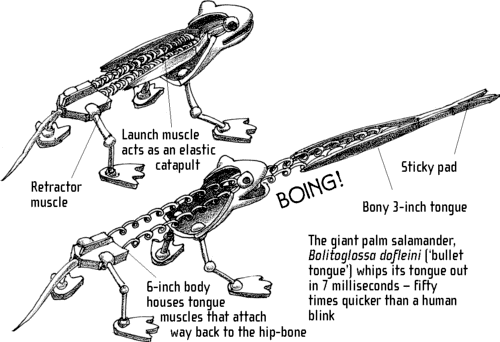

THE MOST

POWERFUL MUSCLE

IN THE WORLD

Duméril's Parisian lab in 1863.

âAxolotl' is the Aztec

word for âwater dog'.

The builders of the

original Mexico cities

were paid in axolotls:

they were useful as

food and medicine. In

Japan they are

popular pets, sold as

WuperRupers

.

Salamanders are committed homebodies, travelling less than a mile from their birthplace over the course of their lives. This can prove fatal when the temperature changes: huge numbers perish each winter.

One species has beaten this problem. The Siberian salamander (

Hynobias

keyserlingii

) can survive in temperatures as low as â50?C by producing antifreeze chemicals before it hibernates. They can stay frozen for many years â some may even have been slumbering since the last ice age ended, 10,000 years ago.

The most persistent myth about salamanders is that they live in fire and can douse flames with secretions from their skin (asbestos was originally called âsalamander wool'). No one knows where or why this idea arose, but they do have a dangerous habit of sleeping in damp woodpiles â¦

Newts are salamanders that return to the water to breed. They are the only vertebrates that can regenerate large parts of themselves, growing new limbs, spinal cords, hearts, jaws, tails and even new lenses and irises for their eyes.

Newt cells can restart the growth process. As the damaged part heals, the cells reverse their original function and turn back into an undifferentiated lump called a

blastema

(from the Greek

blastos

, bud) from which the replacement limb or tissue grows. If a blastema is moved to another part of the salamander's anatomy, the missing bit will start growing there.

How the cells know what to grow isn't understood, but salamanders are being studied closely to see whether human tissue could be stimulated to regenerate. Also, because malignant tumours seem to grow in a very similar way â injecting cancerous tissue into newts can also cause a new limb to grow â they may hold important clues in the fight against cancer.

S

corpions were the first predators to crawl out of the sea on to the land, and they have evolved very little in the last 430 million years because they are very good at what they do. In their prime, during the oxygen-rich atmosphere of the Carboniferous period, scorpions as big as dogs roamed the land, and in the sea giant water scorpions grew to twice that size. Like their younger arachnid cousins, the spiders, scorpions are tough and adaptable, putting up with sub-zero temperatures and desert heat. They can even survive two days completely submerged in water. They are found on all major land masses except Greenland and Antarctica. For 200 years, an illegal immigrant colony of yellow-tailed scorpions (

Euscorpius flavicaudis

) has lived in the harbour wall at Sheerness in Kent.

Isidore of Seville

believed that

scorpions were

formed from the dead

bodies of crabs and,

though very fond of

the smell of basil,

will never sting the

palm of your hand

.

Part of this indestructibility is due to their highly efficient metabolism. They eat slowly but for several hours at a time, dissolving their prey with powerful stomach juices, and leaving behind a small ball of indigestible tissue. A single meal can increase their weight by a third, and some species can survive on that for a year, storing their food as glucose in a large liver-like organ. They burn energy at a quarter of the speed of insects and spiders and very few scorpions ever need to drink. This gives them an advantage as predators but they are also very well equipped when they do need to kill. They have two sets of eyes: one to tell them the time of day or night and a more complex set, with lenses and retinas, that are the most light-sensitive organs of any invertebrate. Using the hairs on their claws they can triangulate the precise position of lunch, picking up vibrations caused by movements as slight as 25 millionths of an inch.

Unusually for an arthropod, a female scorpion gives birth to live young. Even more extraordinarily, some species are pregnant for longer than humans. They are one of the very few invertebrates to have independently evolved a womb where embryos are fed by teats linked to the mother (rather than by the yolk of an egg). Labour can take days, with up to a hundred offspring scurrying up their mother's claws to nestle on her back underneath her sting, so nothing can get to them. Nothing that is except the mother, who, if suddenly peckish, may snack on them herself.

Despite the widespread myth, scorpions do not go mad and sting themselves to death when a drop of alcohol is placed on them, or when confronted with fire, as they are immune to their own venom. Of the 1,500 known species of scorpion, only twenty-five have stings that are dangerous to humans; most are no worse than a bee sting. Scorpion venom can even save lives: protein from the Israeli yellow scorpion's (

Leiurus quinquestriatus

) venom has been used to kill brain tumours.

Scorpions are fluorescent under ultraviolet light as a result of special proteins in their exoskeletons. As they can't see this themselves, no one is quite sure why. It might be to mimic insect-attracting plants, to warn off predators or even to act as an in-built sunscreen.

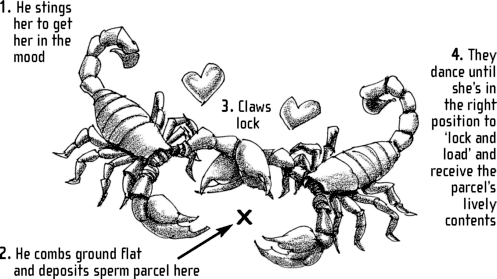

DIRTY DANCING: SCORPION âFOREPLAY'