The Book of Animal Ignorance (30 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

O

nly one in a hundred shark species attacks people. In 2005, there were just fifty-eight shark attacks reported worldwide. Only four people were killed. Wasps kill as many people in Britain every year and jellyfish in the Philippines ten times as many. In the US, both dogs and alligators kill more people than sharks. To put it another way, in an average year in New York there are 1,600 cases of people biting people. Sharks have far more reason to be scared of us. We kill at least 70 million a year for food (despite the fact that some shark flesh tastes of urine, both ârock salmon' and âhuss' are sharks) and for their livers (which are used in haemorrhoid cream).

If you turn a

shark upside

down it will go

into a trance-like

state called âtonic

immobility' for

fifteen minutes.

No one knows

what causes it

.

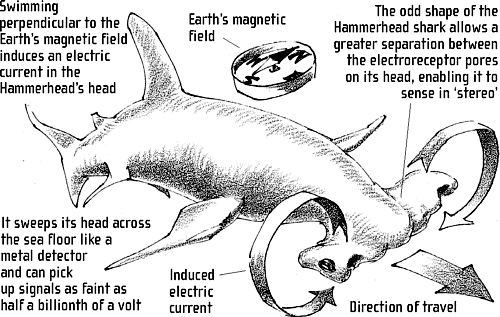

It's a good job sharks find people a bit on the bony side and prefer seals. They are armed with a terrifying range of surveillance equipment. Two-thirds of a shark's brain is dedicated to smell: it can detect blood diluted in water at strengths of one part in a million and from a distance of a quarter of a mile. Nor does lunch have to be bleeding for the shark to know it's there. Shoaling fish exude chemicals to warn colleagues when danger threatens. Sharks intercept these signals, scenting fish that are not even wounded, merely nervous. A shark's ability to detect low-frequency sounds means it can hear the very heartbeats of fish from far away, and pressure-sensitive receptors along its body allow it to âfeel' the remote movements of prey through the water. Cells under the skin of its head enable it to pinpoint tiny changes in magnetic fields and minute electrical impulses. These not only help it to navigate as if using a compass, but provide yet another killing aid: sensing individual muscle movements of a distant fish even

when buried under sand. Some sharks even have a depth gauge in their middle ear. Equipped with this sophisticated gear, predatory sharks are able to hunt in total darkness.

Although in daylight they have perfectly good eyesight, these night raids must be their undoing. Items found in sharks' stomachs include beer bottles, bags of potatoes, a tom-tom drum, car number-plates, house bricks, a suit of armour and a whole porcupine. A single tiger shark was found to have swallowed three overcoats and a raincoat, some trousers, a pair of shoes, a driving licence, a set of antlers, twelve intact lobsters and a whole hen-house full of partly digested chickens.

The female frilled shark holds the world record for the longest pregnancy in nature: over three years. The largest egg in nature belongs not to the ostrich but to the female whale shark. Discovered in 1953, it was 12 inches long, 6 inches wide and 4 inches thick. The embryos of female sand tiger sharks kill and eat each other in the womb. But since records began in 1580, fewer than 2,500 shark attacks on humans have been reported. This is equivalent to about 6 per cent of the number of Americans injured by lavatories in 1996 (43,687).

Male sharks do not have penises. Which probably explains a lot.

RADIOHEAD

D

omesticated sheep (

Ovis aries

) may only exist because of humans â but we, in our modern form, only exist because of sheep. First domesticated in the Middle East and Central Asia around 9000

BC

, some time after dogs, reindeer and goats, all modern sheep can trace their lineage back to two ancestral breeds, one probably extinct, the other, the tiny â and now endangered â mouflon (

Ovis musimon

). Sheep, even more than their close relatives the goats, were responsible for the greatest lifestyle shift in human history, the transition from hunter-gathering to farming. Goats were perfect for nomads, but sheep, because of their tendency to flock and their ability to graze on the toughest grass, allowed us to stay in one place. Sheep fertilised the ground they grazed on, allowing agriculture to flourish, and their flesh and milk gave us a break from hunting. To get the best out of sheep, they needed to be herded and guarded, leading to larger human settlements (and more work for the recently domesticated dog). Interestingly, the Latin for sheep,

ovis

, and the English

ewe

both derive from the Sanskrit

avi

, which has its roots in

av

meaning âto guard or protect'. Looking after sheep gave us civilisation.

It took 3,000 years for our ancestors to discover that by selectively breeding sheep they could encourage their fluffy

undercoat to grow longer than the bristly guard hairs (called âkemp'). The result was first felt and then wool, and suddenly humans had yarn, then looms and textiles. If sheep farming was the first industry, wool became the first great trade commodity. By the Middle Ages, wool drove the economies of Europe: the Renaissance was largely financed on the profits from the wool trade. Today, synthetic fibres have dramatically reduced wool production in Europe and America: 60 per cent now comes from Australia, New Zealand and China.

Soay sheep from St Kilda,

were isolated for 4,000

years and reverted to a feral

state. They have to be

peeled, not shorn, and stare

in blank incomprehension at

sheepdogs. All you need to

keep them is a pair of

binoculars

.

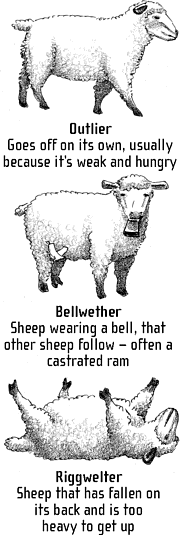

Perhaps this apparent readiness to offer themselves up for our benefit has fed into their cultural role, which, historically, has been all about sacrifice. Unlike the more sexually suggestive associations attached to the goat, sheep have invariably found themselves being offered up in thanks, or having to symbolise innocent victimhood. The sacred texts of Judaism, Christianity and Islam overflow with lambs, flocks and shepherds. More recently, sheep have become a byword for conformism and stupidity, which is not only ungrateful but wrong. Far from being dim, sheep have good memories: they can recognise faces of other flock members and the face of their shepherd for up to two years. This facility has long been known by hill farmers, whose flocks have become âhefted' to a particular territory. Shepherds and dogs initially teach them which ridges, boulders and streams mark the grazing boundaries. The ewes then teach this to lambs and it gets passed on from generation to generation, sometimes stretching back hundreds of years. The loss of âhefted' flocks was one of the hidden costs of the 2001 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease, in which seven million British sheep were slaughtered. More recently, super-smart sheep have learned how to cross cattle-grids by taking a good run-up and then rolling up in a ball to cross them, SAS-style.

N

o one is born with a fear of snakes: it has to be learned. Even then it's not really rational. In Florida, which is home to more than seventy different types of snake, 500 times as many people are bitten by dogs and far more people die from both bee stings and lightning strikes than from snakebites. The chance of being hurt in a road accident in Florida is at least a hundred times higher than that of being bitten by a snake. Snakes are not aggressive and do not chase after people. Even if they did, you'd just walk away. A rattlesnake travels at a top speed of 2 mph. The fastest snake ever recorded, a black mamba (

Dendroaspis polylepis

, âmany-scaled wood snake'), clocked up only 10 mph.

Snakes have two

penises hidden

inside their

bottoms. The one

on the right is

often larger,

suggesting that

they are âright-penised'

in the

same way most

humans are

right-handed

.

The smallest known snake is the burrowing thread snake (

Leptotyphlops bilineata

, âdouble-lined skinny blind-eye'). It is 6 inches long and as thin as a matchstick. No one knows how large the largest snakes are because the really big ones have never been brought back to be measured scientifically. At the beginning of the twentieth century, a reticulated python on the island of Celebes was said to be 33 feet long, and a green anaconda in Colombia reportedly measured 37.5 feet. No snakes as long as these have been reported for a hundred years. Snakeskin is so valuable that no snake survives long enough to grow to that size.

The lips of boas and pythons are the most sensitive heat-detectors in nature. They can sense temperature differences of a 1000th of a degree between an object and its background and judge its direction and distance with similar accuracy. Such snakes find and kill their prey in total darkness by sensing their

body heat alone. The heat-detectors of rattlesnakes and pit vipers are so acute that a deaf, blind snake that has had its tongue cut off can still accurately strike its prey. Many snakes can taste air and see heat.

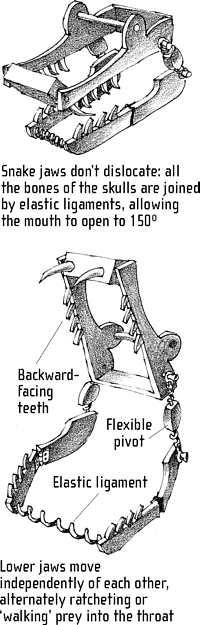

There is no such thing as a vegetarian snake. Snakes eat nothing except other animals. Anacondas and pythons can open their mouths wide enough to swallow deer and goats whole and a python is easily a match for a leopard or a crocodile. Whether they get indigestion is not known, but the powerful acids in their stomach mean a snake will explode if given Alka Seltzer. Most snakes eat once a week; some only eight or ten times a year. After a big meal, a python can go for a whole year without eating and female adders don't eat for eighteen months.

WHEN DINNER'S BIGGER

THAN YOUR HEAD

Keen sunbathers, snakes, like many other animals that strike fear into people, do not like to be disturbed. When this happens, most of them wriggle away. The Sonoran coral snake (

Micruroides euryxanthus

âyellow-banded small-tail') accompanies this with small, regular, high-pitched farts. Grass snakes (which are otherwise harmless) emit a disgusting stench of rotten garlic from their anal glands. They then vomit the contents of their stomachs all over the path. If that doesn't put you off, they flip over on to their backs and lie motionless with their mouths open and their tongues lolling out. Whether this is a defence mechanism or just bad acting is unknown. Most researchers never get close enough to ask them.