The Book of Animal Ignorance (32 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

T

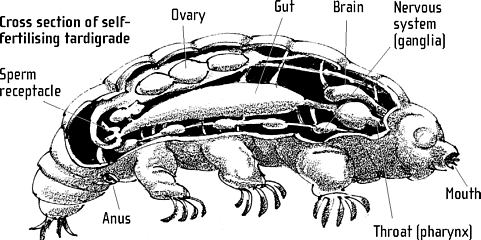

ardigrades are the toughest animals on the planet. Also known as âwater bears' and âmoss piglets', they sound cute, but don't be fooled. They live anywhere there's water â 5 miles down in the ocean; on the polar ice-caps; in radioactive hot springs; on top of the Himalayas; on forest floors; on the bottom of lakes; on wet beaches; in Alpine meadows; in the miniature ponds created in the cups of leaves; in the moss on your roof; on the ground where your dog pees each morning. They are plump, microscopic animals that fall somewhere between the annelid worms and the insects. Only a twentieth of an inch long, they have a head, four pairs of stubby, clawed legs and a sausage-shaped, opaque body. They're called water bears because of the way they look and move (although they're more like a section of frayed, rumpled leg-warmer) and moss piglets because moss is one of the best and easiest places to find them.

A tardigrade in

suspended

animation is called

a âtun', because it

looks a bit like a

tiny wine barrel

.

INSIDE THE RESURRECTION MACHINE

There are 800 recorded species of tardigrade, with at least 10,000 still to be named and they are distinctive enough to have

their own phyla. Most land-dwellers feed on plants and fungi, but many are carnivorous, sucking up nematode worms, rotifers and other tiny creatures. The water-dwellers (who can live 100,000 to the pint) seem to survive without eating at all for long periods, although some are parasites, living on sea cucumbers and barnacles. Many species are all female. As they aren't speedy at getting around (âtardigrade' means âslow-stepper'), they rely on the wind or splashing raindrops to move them to new habitats. Under those circumstances, being able to fertilise your own eggs is a definite advantage: you can populate a new clump of moss all by yourself. Other species reproduce sexually, in a topsy-turvy kind of way (the female inserts a tube into the male and steals his sperm). Tardigrade eggs are spectacularly beautiful, shaped into multi-pointed stars and dimpled spheres that look like chic lampshades, although their practical function is to keep their contents moist and safe from being squashed.

What really sets tardigrades apart is their ability to enter a state of suspended animation. If their water supply dries out, they dry out too. All life processes come to a complete halt and they become totally inert â but they are not dead. This condition, known as cryptobiosis, was first identified in 1776. Some scientists believe it may hold the clue to the origins of life itself. The tardigrade expels all its water and breaks down its cell fats into a sugar called trelahose, which binds and protects all its vital organs. Then it waits â for as long as a hundred years â for a single drop of water to revive it.

In this âdead' state, tardigrades are practically indestructible. They have been frozen to within a degree of absolute zero (â272°C) and heated to temperatures of 151°C. They have been placed in liquid helium for a week, and given doses of radiation a thousand times greater than the fatal dose for a human. They have been immersed in chemicals and squeezed by pressures six times greater than those at the bottom of the ocean; but like living granules of instant coffee, with one drop of water, back to life they come.

T

ermites have evolved the most sophisticated family organisation of any animal and it's based around monogamy. Despite living in colonies containing millions of individuals, breeding termites mate for life. Some species only have one king and queen per colony; others have several and, unlike those of ants or bees, these are proper marriages not brief flings: there are couples still mating years later. This has helped make termites, with ants, the most successful insects of all: if you added all 2,600 termite species together, they would account for 10 per cent of the planet's total biomass. Unfortunately their high-fibre diet means they also produce 11 per cent of global methane emissions, second only to ruminants like cows and sheep.

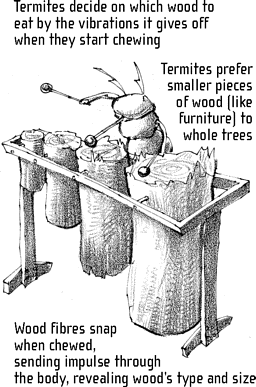

HOW DOES YOUR WOOD SOUND?

But life doesn't always run smoothly, even for termites. In the species

Zootermopsis nevadensis

the divorce rate is running at about 50 per cent. Sometimes the males walk out; often the female invites in a new male with predictably violent results. Touchingly, rejected termites tend to take up with one another. Marriage leaves the male termite relatively unaffected, although he usually dies first. The queen, however, can swell to 300 times her original size, as her ovaries expand. The queen of the Indian mound-building termite (

Odontotermes obesus

) lays an egg a second, or more than 80,000 a day. If the nest is attacked, the workers have to drag her to

safety, as she is too fat to move of her own accord.

To make things worse, termites are in the middle of an identity crisis. In 2007, DNA research revealed that they are actually cockroaches. Their former order

Isoptera

(âequal wing') has been abandoned and they have been moved into

Blattodea

(

blatta

is Greek for cockroach). The theory is that they evolved from their cockroach-like ancestors when they developed the ability to eat wood.

Didgeridoos

are made from

eucalyptus

logs hollowed

out by

termites

.

It's the blind workers who do the wood-munching, feeding the rest of the colony from their mouths or bottoms. They are like mini-cows, with a multi-chambered stomach to break down cellulose. Their guts are home to 200 types of microbes which all help turn the wood into energy. Studies of these tiny organisms are being funded by the biofuel industry to see if they hold the key to extracting clean-burning fuel from corn. In some species, workers arrange their droppings into combs which grow fungi, ensuring a supply of rich protein, even during the dry season.

A termite nest is the most complex animal structure not built by us. The external mound can be over 25 feet high, protecting the nest from the fierce sun, acting as an air-conditioning duct by releasing the heat and carbon dioxide generated by the termites and their fungus gardens and replacing it with fresh oxygen. The Formosan subterranean termite (

Coptotermes formosanus

) even fumigates its nest with naphthalene to repel ants and nematode worms. As it doesn't occur naturally, no one knows how â or from what â it is made.

Termites can burrow

through concrete. In

North America, they

cause more damage

than fires and floods

put together; the

annual global termite

damage bill now

exceeds $5 billion

.

Termites are one of the most popular culinary insects: they contain 75 per cent more protein than rump steak. In the Amazon basin, the Maue tribe barbecue them while the Kayapo fry them in their own juices or use them crushed as a condiment. In Nigeria you can buy termite stock cubes.

F

ew animals spook us like the toad. The witch's right-hand animal, they have been feared throughout history as ugly, poisonous creatures of the night. Touching them might give you warts and meeting their stare could turn you epileptic.

In East Anglia, to become a âtoadman' was to make a pact with the Devil, the most dangerous initiation ritual of British folk magic: all your power was focused in the bone of a toad, which no one else was allowed to see or touch.

Wearing the legs torn from a toad guarded against skin disease. Carrying its tongue made you irresistible to women. Breast cancer could be cured by rubbing a live toad over your chest, and the best protection against witches was to bury a toad in a bottle near your door or hearth. Killing them was strictly taboo.

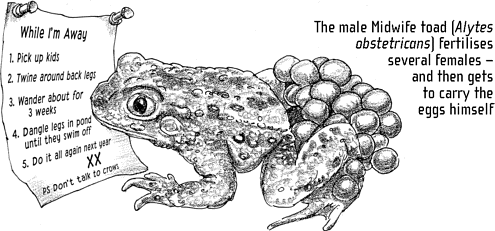

Despite all the bad press, toads, taxonomically speaking, are members of the frog family. There are 350 species and the main differences are skin and teeth. Frogs tend to have tiny teeth and smooth skin; toads have no teeth and thick, warty skin, and usually walk rather than hop.

âToady' (as in âsycophant')

comes from

âtoad-

eater', one half

of an eighteenth-century

pair of con

artists, who would

swallow a toad in

public and then beg

his quack doctor-partner

to cure him

with a âmagical elixir'

.

Also, unlike most frogs, toads are poisonous. They secrete a milky fluid from their warts and from a pair of glands behind their eyes â the âtoad spittle' of legend. In some species this venom contains hallucinogenic compounds and can be âmilked' for recreational use. Unfortunately, it also contains powerful steroids which cause irreparable damage to the heart. Licking or kissing toads is likely to make you sick long before it gets you high.

Twenty tons of toads are squashed

on British roads every year. This is because they have followed the same path, century after century, to ancient breeding ponds, which often means crossing busy roads. Purpose-built subterranean toad tunnels have helped, easing the passage of as many as 1,500 toads in a single evening.

âToad-in-the-hole' was originally steak encased in batter, until steak became too expensive and was replaced by sausages. The name was taken from a now-forgotten public craze of the nineteenth century. Hundreds of examples were reported of live toads being discovered entombed in the middle of ancient rocks. âToad-in-the-hole' hysteria peaked in the 1830s when William Buckland, the Oxford Professor of Geology, buried a number of toads in stone blocks to test their survival skills. Although some lived for as long as two years, most died and public fascination waned.

A more recent toad mystery took place in a Hamburg pond in 2005, when toads started exploding during the mating season. More than a thousand toads, swollen to three times their usual size, crawled out of the water, making eerie screeching noises, and blew up, propelling their entrails up to a yard away.

Initial suspicions of a virus or industrial pollution turned out to be wrong. The toads were being attacked by super-smart crows. The birds had worked out that, with a single strike through the toad's chest, they could remove its liver. The toad's own defence mechanism did the rest. As they puffed themselves up to intimidate their attacker, they forced their own intestines out through the wound at high pressure, in a kind of fatal hernia.