The Book of Animal Ignorance (27 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

T

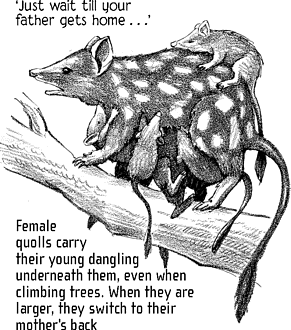

he five species of quoll are known as âmarsupial cats', although they aren't remotely related to the felines. They don't look much like them either: their snouts are longer, more like a mongoose's or a ferret's, and they have spotted coats and long bushy tails (their family name

Dasyurus

means âhairy tail'). But they fill the cat-shaped hole in the marsupial world, surviving as nocturnal, solitary predators with the most powerful bite for their size of any animal except their closest relative, the legendary Tasmanian Devil (

Sarcophilus laniarius

).

This killer streak even surfaces during sex. The female Northern quolls (

Dasyurus hallucatus

) all come into season at the same time each winter, leading to a free-for-all, as males try to mate with as many females as possible. Grabbing the female's neck in razor-sharp jaws, they drag them off for an average mating session of three hours, and sometimes for as long as twenty-four. It takes this long because they don't produce many sperm and need to ejaculate repeatedly to ensure conception. There's a lot of screeching and biting, as the females crouch with their eyes closed thinking of the spring, but many get injured, and some are even killed and partially eaten by their mate.

In the case of the Northern quolls, at least, they get their own back. The males often don't recover from the exertion of the rut. They lose weight, become anaemic, their scrotum shrinks, their fur falls out and they get infested with lice. Within a week or

two they die, martyrs to their genes. This reduces competition for food, giving the females and their offspring a better chance of survival, but also avoids the risk of incest the following season.

The Northern quoll is the smallest of the five and although it's not much larger than a guinea pig, it is fearless, taking on rats, snakes, lizards and pretty much anything that crosses its path. Unfortunately, this includes the poisonous cane toad (see above), which has encroached on its territories, and which it eats before it realises the danger. The population decline is now so steep that conservationists and local Aboriginal groups in the Northern Territories have transported small groups of Northern quolls to outlying toad-free islands.

All the Australian quoll species are threatened, both by introduced predators and by their own adaptive shortcomings. A recent test with the Eastern quoll (

Dasyurus viverrinus

) demonstrated that it couldn't tell the difference between the call of a fox and that of a cow. It is now only found on Tasmania and, although it regularly pops out thirty young, only the first six to find a nipple survive.

Even the Spotted-tailed or Tiger quoll (

Dasyurus maculatus

), the largest carnivore on mainland Australia, has been added to the endangered list, as its population has shrunk to fewer than a thousand. Its version of the quoll âsuicide gene' is to site its communal dung-heap in the middle of bush roads.

The word âquoll' was first

recorded by Captain Cook in

1770. It comes from

dhigal

in the Guugu Yimidhirr

language of Northern

Queensland, which he

transcribed as

Je-Quoll.

In 2001, Michael Archer, director of Sydney's Australian Museum, suggested that to save quolls from extinction, people ought to take them up as pets: âInstead of canoodling with dogs and cats, cuddle a quoll instead!'

âT

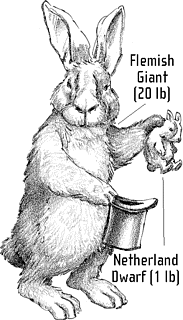

he introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting.' Rarely has a human prediction proved more wrong. These were the words of Thomas Austin, an English settler in Australia who released twenty-four rabbits on his farm in 1859. Ten years later, there were so many across Australia that even a cull of two million made no dent in the population. By 1950, when the myxomatosis virus was introduced as a biological control, there were over one billion Aussie rabbits, the fastest spread of mammals ever recorded. As a result, an eighth of all native Australian mammals and an unquantifiable number of plant species perished, their habitats destroyed by overgrazing and erosion. Myxomatosis worked â the rabbit population was decimated, but the small number that survived have bred a genetic resistance to the disease, so a new, less effective virus (rabbit haemorrhagic disease) was introduced in 1995. The population is currently a hundred million and growing.

WORLD'S 3rd MOST POPULAR PET

What makes the European rabbit (

Oryctolagus cuniculus

) so successful? Firstly, diet. They will eat most things that grow, and in quantity: a single rabbit can eat enough grass to stuff a decent-sized pillow every day. Secondly, unlike hares and most other rabbit species, they run a communal burrow system which supports a large number of breeding females. And finally, they breed like â well â rabbits. A doe is usually either pregnant, lactating or both at once; she can

produce thirty kits a year and they are all able to reproduce within six months of being born. Males tend to disperse to new colonies, females stay put to breed until the warren gets too crowded. Unless predation or disease intervenes, rabbit populations spiral.

Despite appearances, rabbits aren't rodents, they are lagomorphs (âhare-shaped'), one of over fifty species, including hares, pikas, jackrabbits and cottontails. Lagomorphs have a special trick: eating their food twice. Whereas a cow chews the cud, they eat their own droppings. Not the dry fibrous spheres we find scattered outside their burrows, but the contents of their large intestine, which look like bunches of shiny green grapes and are full of bacteria, generating essential nutrients, especially B vitamins. Strictly speaking, despite their provenance, these are not faeces, but food. They are coated with rubbery mucus to protect them from the digestive process and rabbits eat them directly from their bottoms.

The Sumatran striped

rabbit (

Nesolagus netscheri

) is so rare

and shy that there is

no word for it in the

language used where it

lives. It was thought

extinct in the 1930s,

and has only been seen

three times since

.

It wasn't until the mid-nineteenth century that the resourceful rabbit became a serious agricultural problem in Britain. When they were first introduced by the Normans, rabbits were a valuable farm animal, kept in enclosed warrens (by warreners) for their meat and fur. Poaching rabbits was a high crime carrying draconian punishment. But by the 1820s, not only were landowners âenclosing' their land with endless miles of hedges (the perfect environment for escaped rabbits), they also unleashed an orgy of shooting, poisoning and trapping of the foxes, martens, stoats and birds of prey that had previously controlled rabbit numbers. Ironically, the âspot of hunting' that Thomas Austin fancied on his new Australian farm transformed the rabbits back home from crop to pest. The once exotic rabbit now costs British agriculture £100 million each year. Ironically, rabbit meat sold for the British table is mostly factory-farmed and imported from China, Hungary and Poland.

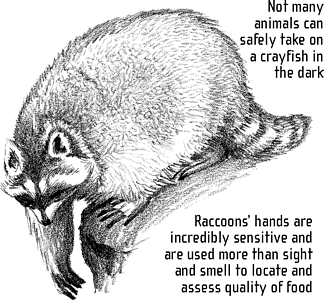

Y

ou can learn a lot about raccoons from the words for them in other languages. The English âraccoon' is derived from Algonquian Indian

arahkoonem

: âthey rub, scrub, scratch.' In Dakota-Sioux, a raccoon is

weekah tegalega

, âmagic one with painted face'. In Abnaki, it's

asban

, âone who lifts up things'. The Delaware Indians called it

wtakalinch

, âvery clever with its fingers'. Spanish colonists adapted the Aztec word

mapache

(âthat which has hands'), although the Aztecs also called it

eeyahmahtohn

(âthe little old lady who knows things').

Raccoons are the best-known wild animals in North America. They have a black mask over their eyes and a bushy tail with between four and ten black rings. They have five toes on each foot and their front paws are provided with thumbs, thanks to which they can lift latches, unscrew jars, disentangle knots, turn doorknobs and open refrigerators. Their paw-prints look like tiny human baby handprints. Raccoons adapt remarkably easily to the human environment and many of them live happily in New York City. They can live to be sixteen in the countryside but urban raccoons eat a similar diet to teenagers, becoming so dependent on French fries and doughnuts that they can't survive in the wild.

Raccoon is a popular

dish in the southern

United States, the

centrepiece for a

traditional âcoon

dinner'. Once the

gamey fat has been

removed, it is excellent

roasted with a stuffing

of sweet potato

.

Fat is a raccoon issue: for some, 50 per cent of their body mass is fat. The fattest-ever raccoon was called Bandit; he lived outside Ice Cream World in Walnutport, Pennsylvania, and loved to feast on peanut butter and blueberry slush puppies. Raccoons are rightly called omnivores. They really will eat anything. They tuck into crayfish, apples, mice, eggs, insects, walnuts, frogs, fish,

sweetcorn, clams, cherries, turtles, acorns, snakes and even road kill. Almost all non-American languages, from German and Finnish to Chinese, Japanese and Bulgarian, call them âwashing bears' because they seem to wash their food before eating it. For a long time, scientists thought this was because they couldn't produce enough saliva to swallow anything dry. In fact, this is not so. They have plenty of saliva, and they're not actually washing what they're about to eat. They do dunk food in water â an odd behaviour called âdabbling' â but it appears they're just sorting out what is edible and not too sharp to ingest. If there's no water about they will still exhibit similar âdabbling' behaviour and they're quite happy to eat food that has dirt on it. In search of food, raccoons are good climbers. They can rotate their back feet through 180° and climb head-first down trees, but they are equally at home in chimneys, haylofts and attics.

HANDSIGHT

Raccoon droppings are crumbly, tubular and flat-ended. DO NOT EAT THEM. DO NOT EVEN TOUCH THEM. They may contain up to 250,000 eggs of

Baylisascaris procyonis

, a nematode worm that can cause severe illness in humans. If you eat the eggs, the larvae can migrate to other tissues, including the brain and eyes. There is no effective therapy. Raccoons look cute but many of them also carry rabies (of which they show no sign). They have bones in their penises (which people in Texas like to carry around for good luck). Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the Pre-Raphaelite poet, kept a raccoon in his Chelsea menagerie. It inspired no poetry, but did manage to disgrace itself by opening and eating its way through a whole drawerful of his manuscripts.