The Book of Animal Ignorance (22 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

M

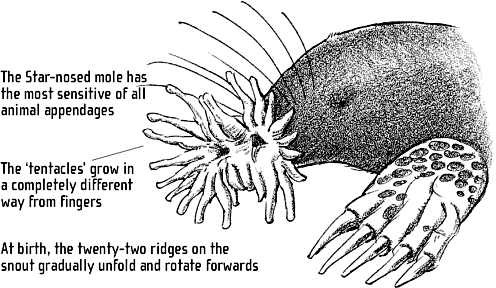

oles aren't blind, but their pinhead eyes can only tell light from dark. What really sets them apart is their noses, which they use for âfeeling' rather than smelling.

The nose of the Star-nosed mole (

Condylura cristata

) is unique. It looks like a pink sea anemone, but is really a twenty-two fingered, non-grasping hand that the mole uses to form a complete picture of its underground world. With a much higher density of nerve-endings than the average clitoris, it uses a similar brain capacity to that used for sight in other mammals, making it more of an eye than a hand.

âMole' comes from

âmouldwarp', Old

English for âearth-thrower'.

The dialect

name was âwoont',

molecatchers were

âwoonters' and

molehills were

âwoonty-

tumps'

.

The Star-nosed mole holds two other records. It has the fastest reactions of any mammal: locating, identifying and eating an insect larva in an average of 227 milliseconds, which is less time than it takes to read the word âmole' and three times faster than most of can us brake at a red light. It is also the only mammal to âsmell' under water, sprouting large air bubbles from its nostrils rather like a child blowing bubblegum.

If a mole goes without a meal for eight hours, it dies. The diet of the European mole (

Talpa europaea

) consists chiefly of earthworms: their tunnels are traps for worms to fall into. They need to eat about a hundred each day. By biting their heads to immobilise them, a mole can keep up to 500 worms alive in underground âlarders'. Moles drink a lot, too, and at least one of their tunnels will come out by a ditch or pond. Contrary to myth, they do not eat plant roots or other vegetable matter.

If short of worms, a mole might dig 150 feet of new tunnels in a day, the equivalent of a human moving four tons (about a thousand shovel loads) every twenty minutes.

Moles are not nocturnal â it's just that we rarely see them. In fact, they work in shifts alternating four hours of frantic digging and eating with four hours of sleep. They are highly territorial and solitary, each animal's territory covering anything up to four football pitches. This solitary life is only relieved for the few hours each spring when they come together to mate, which sometimes happens above ground.

For the rest of the year, moles use their forty-four teeth to make sure other individuals keep their distance. This includes the females, who are equipped with another mammalian first: a pair of ovaries-cum-testicles that release eggs in the spring and testosterone in the autumn, when they need to defend their ground. There are differences. Males are slightly larger and their tunnelling behaviour is different. Females build an irregular network, whereas males, of course, tunnel in long, straight lines.

Molehills consist of exceptionally fine soil, prized by gardeners as seed compost. In the second half of the nineteenth century, moleskin provided molecatchers with a very good income. It took a hundred skins to make a waistcoat, and by the turn of the century several million British moleskins were being exported to the USA annually.

The British mole population is now estimated at over thirty-five million. In 2002 the post of Mole-catcher Royal was revived with the appointment of Victor Williamson at Sandringham.

STARFACE

A

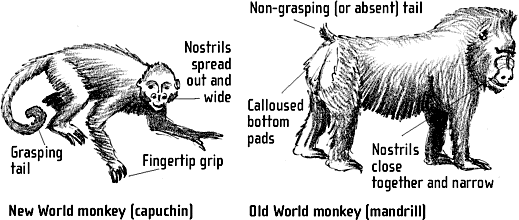

nyone who's taken children to a zoo will know the tractor-beam-like attraction that monkeys exert. A monkey enclosure is like a 12A movie â scenes of mild peril with some sexual content. Children like monkeys because they feel a direct connection with them, and they are right: only the apes are closer relatives. It's interesting that within a few decades of the word âmonkey' first being used (1530, although its origin is obscure), we had already begun to use it as an affectionate nickname for children.

The White uakari is one

of the oddest-looking

of all monkeys. It lives

in the Brazilian rain

forest where its bald,

bright-red face and

rather human ears have

earned it the nickname

âthe Englishman'

.

Wherever they are found in the world, monkeys live in big groups. Their relatively large brains, and the intelligence they confer, have enabled them to cope with the complex interactions required to keep a social order going. The more we learn about monkey societies, the more they seem like us. It's obviously going to delight seven-year-old boys to discover that among Angolan black-and-white colobus monkeys (

Colobus angolensis

), a burp is counted a friendly greeting (like many monkeys they're leaf-eaters, so wind is a constant in their lives). Also, the widespread use of grooming to suck up to the dominant male has a definite schoolboy logic to it, although most schoolboys stop short of removing dead skin and lice from the playground bully.

More grown up human behaviour also finds its monkey equivalent. Monkeys plan ahead: Grey-cheeked mangabeys (

Lophocebus albigena

) make decisions based on the weather, remembering the location of particularly good fig trees and waiting for the sun to shine before setting out on fruit-picking expeditions. Vervet monkeys (

Chlorocebus aethiops

) display a very

human attitude to booze. On the Caribbean island of St Kitts they have learnt to hang out near bars, and finish the cocktails people leave behind. The majority are social drinkers who imbibe in moderation with other monkeys. They prefer their alcohol to be diluted with fruit juice and never drink before lunch. Others refuse to drink at all, but 5 per cent are serious binge drinkers who consume as much hard liquor as they can, make a lot of noise, and start fights, before finally passing out.

Drunkenness is not the only vice we share. An experiment with rhesus macaques (

Macaca mulatta

) revealed that they would âpay' to look at pictures of the faces and bottoms of high-ranking females by forfeiting their usual reward of a glass of cherry juice. With low-ranking females, however, the researchers had to bribe them with an even larger glass of juice before they'd pay any attention. Some species have even taken the law into their own hands. Pigtailed macaques (

Macaca nemestrina

) âelect' senior monkeys to break up fights and keep order. Their authority rarely requires the backup of force, but as soon as the police monkeys are removed, cliques rapidly form and social cohesion breaks down.

For all the similarities there is a gulf between humans and monkeys that only our imaginations can fill. Macaques, smart as they are, know if we're imitating them but can't make the leap and imitate us back. A deep bond remains, nonetheless, and may even be hard-wired. A Canadian research team recently found that, up to the age of three months, newborn humans respond as positively to the calls of rhesus monkeys as they do to human speech.

FROM NOSE TO TAIL

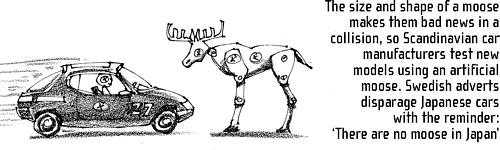

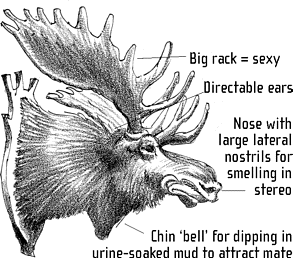

M

oose (

Alces alces

) are, by a wide margin, the largest living members of the deer family. A bull moose weighs three times as much as a red deer stag. The weight of his antlers alone would exceed the personal baggage allowance on international flights (50 lb), and are wide enough for a child to sling a hammock between them. Moose have grown big to cope with the cold: they are only found in the high latitudes of the northern hemisphere. Big is better for keeping warm (a lower surface-area-to-volume ratio helps prevent heat loss), which is why so many ice-age mammals grew so large.

Moose have a double layer of insulating fur, and long legs for wading through snow; even their newborn calves seem happy in temperatures of â30°C. More troubling is warm weather: they can't sweat, and fermenting vegetation turns their stomach into a furnace. In winter, temperatures much above â5°C will set them panting or lying flat in the snow to cool down. During the summer they spend a lot of time wading in water for the same reason.

Moose antler is the

fastest-growing

animal tissue,

sprouting an inch a

day. Antlers are

sensitive enough for

the moose to feel a

fly land on them

.

WHY THE LONG FACE?

Moose are notoriously difficult to keep in captivity. Unlike most other deer, who can browse happily on twigs or graze grass, they are specialised feeders. An adult moose needs to eat the equivalent of a large straw bale of vegetation every day, chewing the cud like a cow to extract the maximum nutritional value. They eat leaves, bark and twigs during the autumn and winter for energy, and marsh plants, when they are in season during spring and early summer, for sodium. Commercial feed can't match this balance, so captive moose tend to die quite quickly. The need for salt explains why you often see them licking roads during the summer. It's also why moose

spend so much time in the water; aquatic plants like water lilies and horsetails are sodium-rich and moose will completely submerge themselves to graze on the bottom of ponds. Reports of them âdiving' are usually exaggerations: they are the wrong shape and size for serious underwater swimming.

What they can do well is to strip trees with their large drooping upper lip (they have no upper front teeth) â the name âmoose' comes from the old Algonquian word

mooswa

, meaning âthe animal that strips bark off trees'. Their eyes can move independently, enabling them to see behind while still looking forward and the long nose, full of soft cartilage and muscle, is a hypersensitive food-finder-cum-sex aid. This nasal succulence wasn't lost on local Native American tribes. According to the eighteenth-century naturalist, Thomas Pennant, the moose's nose was the âperfect marrow, and esteemed the greatest delicacy in all Canada'.

In Europe moose are called elks, from the Latin

alces

, and were first described by Julius Caesar in 50

BC

. The elk became extinct in Britain in the Bronze Age but the name lived on and was used to describe any large deer. When English settlers reached America, the commonest deer,

Cervus canadensis

, reminded them of its British relative, the red deer (

Cervus elaphus

). As a result, it acquired the name âelk' and the other huge and unfamiliar beast continued with its local name, âmoose'.