The Book of Animal Ignorance (17 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

S

nuffling in the dark and gorging on insects, the hedgehog hasn't changed much in fifteen million years. But, in spite of regularly topping the polls as the UK's favourite garden animal, the British hedgehog population is now in freefall. It has halved in the past fifteen years and the current estimate is below a million. If this continues there will be no British hedgehogs left by 2030.

Half die before they reach their first birthday; only 1 in 100 makes it to five, and 15,000 are squashed on British roads each year (down from the mid-1990s peak of 100,000). Road carnage combined with the use of powerful insecticides and the destruction of the grassy field margins that hedgehogs like to nest in make it hard to feel optimistic. Even âurban hedgehogs' aren't as adept at surviving in cities as foxes. They fall into swimming pools, get puréed by lawnmowers or wedge their heads into food containers and starve to death (McDonalds have now changed the design of their McFlurry cartons to make them hedgehog-proof). Many also die from diarrhoea caused by well meaning humans leaving them bread and milk. The best way to help a hedgehog is not to feed it but to turn it loose in your vegetable patch. A single adult can eat 250 slugs in an evening.

The fox knows

many things; the

hedgehog, one big

thing

.

ERASMUS

Ironically, because of their âspiny ball' defence, hedgehogs have very few natural predators. Badgers are the only animals with claws strong enough to prise open a rolled hedgehog, although hungry foxes have been known to urinate on them to force them to unroll. Hedgehogs also have an extraordinary immunity to poison. It takes more chloroform to put a hedgehog to sleep than any other animal of comparable size and they can survive a bite from an adder that would kill a guinea pig in five minutes.

This resistance offers a clue to the strangest of all hedgehog behaviours: âself-anointing', which involves them contorting themselves to coat their own back with gobbets of foaming saliva. Hedgehogs have been observed self-anointing after chewing on the poisonous skin of a toad, thereby creating a toxic mousse for their spines. This makes them even less attractive to predators, but it doesn't entirely explain why the smell of shoes, cigar butts, furniture polish, creosote, coffee, boiled fish, face cream and distilled water should also stimulate the same behaviour.

The word

heyghoge

is first recorded in 1450 and this quickly splintered into regional nicknames like highoggs, hedgepigs, hoghogs and fuzzipeggs. Before that, the Anglo-Saxons had called them

igl

and the Normans, âurchins', after the Latin for hedgehog,

ericius

. This came from the ancient root

gher

-, meaning âto bristle' (which also gave us âhorror').

An adult hedgehog bristles with over 5,000 spines. They are hollow hairs, reinforced by keratin, the same substance our nails are made from. They are extremely strong; a hedgehog can be picked up by a single spine without it breaking. Considering the physical barrier, hedgehogs of both sexes are remarkably promiscuous, mating with ten or more partners each season and sometimes several on the same night. It is never face-to-face, despite Aristotle's confident assertions. The male circles a female for hours, snorting loudly until she spreads her back legs, flattens her spikes and points her nose upwards. Copulation is very brief and noisy and, once sated, the male immediately trundles off, taking no further interest in the female or the rearing of his offspring.

V

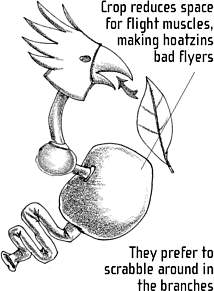

ery few birds live by munching on vegetation. It's heavy, low in energy and slow to digest, not the ideal fuel for flying. But the strange hoatzin (

Opisthocomus hoazin

) â pronounced âwatseen' â of the South American river swamps has actually developed a stomach like a cow's to cope with its diet of leaves.

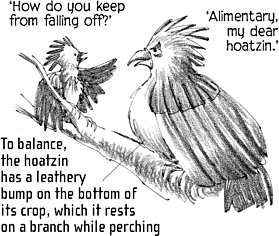

The hoatzin's crop is enormous, fifty times larger than its stomach, accounting for almost a third of total body-weight. And unlike most birds, where it is used for storage, the hoatzin's crop does most of the digestive heavy work. Like the foregut of a cow, it is full of bacteria and enzymes which break down the cellulose in the leaves. An amazing 70 per cent of the fibre gets digested, but as with cows, this takes time. Hoatzins take two days to digest a meal, the slowest of any bird.

The downside of eating like a cow is smelling like one, which is why the hoatzin is known as the âstink bird'. The manure-like pong is produced by fermenting fatty acids in the crop and has kept them mostly out of the human food chain, although their eggs are eaten. The intrepid American ornithologist William Beebe cooked and ate a hoatzin in 1909 and declared it âclean and appetising'. More recently, microbiologists have studied the crop bacteria because of its ability to neutralise poisons in the toxic foliage the bird eats. Transferred to cows and goats, these might allow them to graze on a wider range of forage, with an enormous increase in yield.

Despite being rather

tame, hoatzin get

stressed by tourists.

Colonies that are

visited regularly

produce double the

level of stress

hormones and lay a

third fewer eggs

.

They are very social birds, living in groups of five to fifty, and are about as large (and clumsy) as chickens. Their weight makes them poor flyers and they spend three-quarters of their time just perching, spreading their feathers to soak up the sun and digesting their toxic breakfast. They look rather prehistoric, with shaggy russet and light brown feathers, a bright blue face, piercing red eyes with large eyelashes and a spiky head crest. They are noisy, too: continually grunting wheezing, and hissing.

What is a hoatzin? Taxonomists still can't agree. Even with genetic analysis they don't quite fit into any of the existing bird families. For a long time they were classed as game birds (

uazin

is the Aztec name for pheasant), then as cuckoos and more recently as doves. Now, most reference sources list them, aardvark-like, as a single species in their own order, the Opisthocomiformes â âones with long hair behind', referring to their large crest.

A BUMPER CROP

Their chicks share a feature with the fossil proto-bird, archaeopteryx: the first two âfingers' of the wing form into two claws. If disturbed, chicks as young as three days old will leap into the water, and clamber back through the branches to the nest using their claws like small monkeys. It's unlikely that the claws are a prehistoric survival; they are just another odd adaptation to life in the swamp, and disappear as the birds grow older.

T

he horse, like the dog and the camel, first carved out its evolutionary niche in the North America of 50 million years ago. In those days, it scampered around the rainforest eating fruit, much as its relative the tapir still does today. But as the planet cooled, and the forests were replaced by vast grass-filled plains, the American proto-horses diversified and adapted themselves to the new environment, eventually crossing the Bering land-bridge into Asia. All our breeds of domestic horse are a single species,

Equus caballus

, descended from these American immigrants; only one wild horse, the Mongolian Przewalski's horse (

Equus ferus

przewalskii

) has survived.

Many cultures still eat

horse, especially Kazakhs,

who even eat horse rectum,

and the French, whose

preference allegedly dates

to the Battle of Eylau in

1807, when Napoleon's

surgeon-

in-

chief advised

the starving troops to eat

dead battlefield horses

.

Horses are animals of the steppe, and many of the adaptations that allowed them to thrive in an open landscape of rough grass continue to affect their behaviour today. Poor diet requires a large digestive tract, so they grew larger. Because they aren't ruminants, horses depend on lots of small meals, to maintain energy levels, rather than one large feast. They are âhind-gut fermenters', absorbing nutrients through their intestines rather than their stomachs, so a change in diet can cause serious problems: over-rich pasture, mouldy hay and unfamiliar or toxic plants can cause colic, or even death. Horses are prey animals: the best defence on the steppe is to run faster than your predator. Hence they have the largest eyes of any land mammal, arranged to give them almost 360? vision. Anything unfamiliar (like a plastic bag) triggers the flight response. Also, because endurance is more important to survival than initial speed, horses' legs became longer and more

powerful, but took time and space to reach top speed. Most humans can beat a horse from a standing start over 50 yards.

This might explain why most of our early interaction with horses seems to involve us killing them for meat. The oldest European hominid fossil, 500,000-year-old Boxgrove Man, was found next to a butchered horse. In their original homeland of North America, the native horse was hunted to extinction by the end of the last ice age. It wasn't until Cortez and his Spanish troops arrived in 1492 that Native Americans met their first modern horse. They called them âbig dogs', quite reasonably, as they had relied on dogs for transport until then.

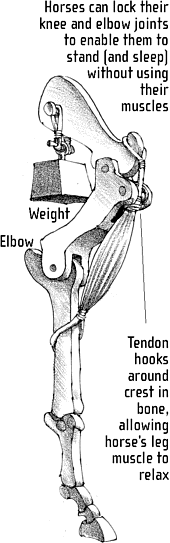

ASLEEP ON THEIR FEET

No one can quite agree when we first started riding horses as well as eating them. They were probably domesticated independently many times and in many places, but the earliest known evidence points to the Ukraine around 6,000 years ago, which is several hundred years before the oldest known wheel. It was one of the great breakthroughs in human history (and an evolutionary meal ticket for the horse). Suddenly, we could travel huge distances quickly and wage wars of unprecedented scale and savagery.

As well as being useful and nutritious, horses acquired huge symbolic value, and were worshipped all over the ancient world from China and Mongolia to ancient Egypt and Celtic Europe. Their importance in this regard has never waned, even as their role in combat, agriculture and transport has diminished. In the UK and US alone, there are 10 million horses ridden for pleasure and profit, creating an income in excess of £60 billion, a figure which outstrips the gross domestic product of most of the world's poorest nations.