The Book of Animal Ignorance (19 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

I

magine what it must have been like being confronted with a kangaroo for the first time. Here's Captain Cook in 1770: âIt was of a light mouse colour and the full size of a greyhound ⦠I should have taken it for a wolf or a wild dog but for its walking or running which it jumped like a hare or deer.' So familiar have kangaroos become that we forget just how different they are from other mammals. A jumping dog with the eyes of a deer, the nose of a hare and the feet of a gerbil. How did it come about?

The kangaroo's

reproductive organs are

worth a detour. The male

has his testicles hanging

above his penis and the

female has three vaginas.

It's perfectly logical. One

is for birth, the other two

are for sex: they carry the

sperm to the two wombs

.

Marsupials or âpouched animals' have ploughed their own furrow for 120 million years, but the large kangaroos (Macropods or âbig-feet') are a relatively recent development. The earliest fossils are 15 million years old, from the time Australia's forests began to recede. Until then, the kangaroos' ancestors had been non-hopping creatures of the woods â there was even a carnivorous sabre-toothed version. Kangaroos adapted to become grass-grazing ruminants, the marsupial equivalents of bison and antelopes, and, like their placental counterparts, they grew larger to house a digestive system that could handle a tough, fibrous diet. Both their stomachs and their large intestines are fermenting vats full of bacteria and enzymes but, unlike cows, they produce not the greenhouse gas methane but another carbon-hydrogen compound: acetate, which they can recycle as energy. Kangaroo gut bacteria may yet help save the planet by producing wind-free cows.

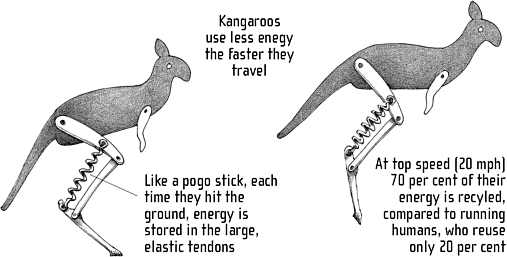

Surviving in the hot, dry outback is all about conserving energy. Hopping is not only fast: it uses less energy than any

other mode of transport. To avoid the daytime heat, kangaroos feed at night (hence their large eyes) and spend their days lying in the shade and licking their forearms to cool down. Even the remarkable reproductive system helps. Kangaroos, famously, have short pregnancies, with the tiny jellybaby-sized foetus crawling into its mother's pouch when only a month old. Less well known is the fact that a female kangaroo can store her embryos for many months in one of her two wombs. This not only means she can swiftly replace a joey that dies; she can also time her births to avoid droughts, saving both energy and water.

This rather undermines the view that marsupial reproduction is âless advanced' than that of placental mammals. The tiny foetus may be underdeveloped but it has what it needs â functioning nostrils to smell the teat and two strong forelimbs to get it there in less than three minutes. (Incidentally, this is why marsupials never developed an aquatic species like whales or dolphins â no gripping arms: no babies.) Once safely in the pouch, the joey latches on, but is too weak to suck: the teat muscle exercises its own portion control, squirting just the right amount of rich milk into its mouth. The mother cleans the pouch, licking up the waste and thereby recycling a third of the milk she produces. When the fully grown joey is kicked out to make way for a new sibling, eight months later, it continues to suckle for several months. Ever mindful of waste, the mother kangaroo's mammary glands produce full-cream and fat-free milk simultaneously.

BIG FEET,

SMALL CARBON

FOOTPRINT

S

everal mammals eat their own droppings, or their offspring's, but only koalas feed them to their young. The mother produces a soup, known as âpap', which the four month-old joeys slurp up, ingesting important micro-organisms and preparing their delicate digestive tracts for the adult diet, which consists entirely of eucalyptus leaves.

Most herbivores don't go near eucalyptus. The leaves are 50 per cent water and contain nasty toxins. But the koala's guts have adapted to process them and they feed on only thirty of the 600 eucalyptus species that live in Australia; they can even tell the age of the leaves by their smell. To qualify as lunch they have to be between a year and eighteen months old, as young leaves have almost no nutritional value and older leaves contain poisonous prussic acid. On the plus side, koalas hardly ever have to drink â they get all the moisture they need from the leaves â but eucalyptus is so low in energy that they spend twenty hours a day asleep, like sloths. This might also explain why they have, proportionally, one of the smallest mammalian brains. Brains burn energy. The koala's occupies only half its cranial cavity, floating in fluid like a prune.

âKoala' means âno

water' in the Dharuk

language. The Dharuk

who lived around

Sydney and Botany Bay

are all long since

extinct. âBoomerang',

âdingo', âwallaby' and

âcoo-

ee!' all come from

the Dharuk

.

Not even sex distracts them from sleep for long. It's very straightforward and takes place on a sturdy branch. The male mounts from behind, bites the female's neck and manages about forty thrusts of his bifurcated penis in twenty seconds. Once thrusting stops, ejaculation (into both vaginas) lasts for thirty seconds.

This perfunctory attitude might throw some light on the female koala's enthusiastic, if mysterious, adoption of lesbian

behaviour when taken into captivity. Romps involving up to five females are commonplace, and outnumber heterosexual encounters by 3 to 1. They also last twice as long. Unfortunately, wild lesbian sex only helps to spread chlamydia, a sexually transmitted bacterial infection which afflicts three-quarters of all female koalas. Also known as âwet bottom', it makes them smell bad and leaves them sterile.

THE EUCALYPTUS GUT-BUSTER

Wild koalas are now officially listed as âlow risk to near-threatened'. Although aboriginal peoples did occasionally eat them, they didn't hunt them to near extinction as was once claimed: their population at the time Europeans arrived is estimated at ten million. What nearly did for them was the fur trade. Until it was banned in 1927, millions of skins were exported each year. Now, despite their iconic status, the koala population may be as low as 100,000, bush fires and road traffic having taken a heavy toll. The Australian Koala Foundation estimates that 80 per cent of their natural territory has been destroyed.

The koala's scientific name,

Phascolarctos cinereus

, means âash-grey pouch-bear' but koalas aren't bears; they are marsupials, close relatives of the wombat.

They have fingerprints that are almost indistinguishable from human ones. All primates have ridged finger-ends to help them climb, but marsupials split from the lineage of primates 125 million years ago, before koalas had evolved. The fact that two lineages independently developed the same trait to do the same job is a good example of âconvergent evolution'.

T

en feet long and weighing up to 20 stone, the komodo dragon (

Varanus komodoensis

) is already the largest living lizard. Now it holds he distinction of being the largest land animal capable of parthenogenesis (Greek for âvirgin birth').

In 2006, two of the three komodos held in UK zoos gave birth despite having had no access to a male. They managed this by a process called âselfing'. In komodos, as in birds (but unlike mammals), it is the female who holds two different sex chromosomes: Z for male and W for female. Each of her ZW eggs has a second mini-egg attached to it, containing a full copy of her genetic information. In the absence of sperm, this gets reabsorbed and âfertilizes' the main egg, producing a set of male (ZZ) non-identical twins.

This may have evolved as a survival strategy. Komodos are excellent swimmers and are only found on a few small islands in the middle of the Indonesian archipelago. A stranded female could populate a new island by mating with her own offspring.

The komodo was first discovered by Western scientists in 1910, despite the many local stories of a fierce dragon that lived in the island forests. In 1926, W. Douglas Burden, a wealthy adventurer, led an expedition to capture a live specimen. He failed, but his account of the trip inspired the Hollywood producer Merian C. Cooper to make the film

King Kong

in 1933.

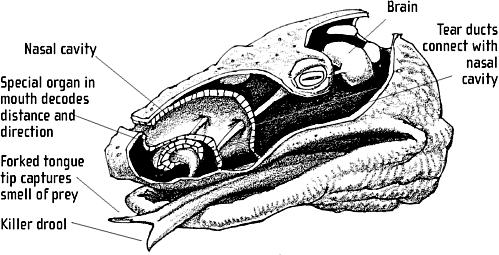

Komodos are often called âliving dinosaurs', but unlike birds and crocodiles they aren't direct descendants. Komodos are monitor lizards, closely related to iguanas and snakes. They are fearsome carnivores, with flat serrated teeth (more like a shark's than a reptile's) and powerful curved claws. Their bite is fatal and their âkiller saliva' is legendary â it contains fifteen virulent strains of harmful bacteria â but recent research has confirmed that komodos are also venomous, with powerful toxins being

secreted from glands in the mouth.

There is only one map

that states âHere be

dragons' â the tiny

copper Lenox Globe of

1507

. Hic sunt dracones

appears over

the eastern coast of

Asia, not far from

Komodo

â¦

As the top predator on their islands, their isolation has allowed them to grow huge. They originally evolved to prey on a now extinct breed of pygmy elephant but will cheerfully take down buffalo, deer, goats, or young komodos. To avoid this, the young spend their early life in the treetops, and when joining a communal kill take the precaution of rolling in the prey's droppings to make themselves as unappetising as possible to their older colleagues.

Komodos eat once a month, wolfing down three-quarters of their body weight in a single sitting. Afterwards, they lie in the warm sun to stimulate digestion and prevent the food rotting in their stomachs. Sex is predictably violent. Males rear up on their hind legs and wrestle to establish dominance and, having succeeded, restrain the female just long enough to insert one of their two penises in her bottom.

They are highly intelligent. Captive komodos recognise their keepers and can perform simple tricks. But keep your shoes on, as Phil Bronstein found out. The newspaper editor and sometime husband to Sharon Stone had his foot badly mauled by a âtame' komodo at the Los Angeles zoo in 2001.

KOMODOS SMELL WITH THEIR TONGUES