The Book of Animal Ignorance (15 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

I

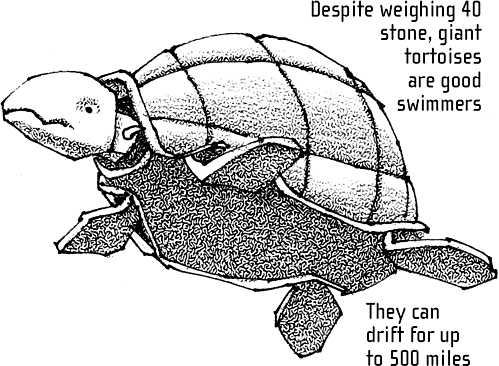

n 2006, Adwaitya, the Aldabra giant tortoise (

Geochelone gigantes

), personal pet of Clive of India, died in Kolkata zoo, aged 255. He was, as far as we know, the planet's oldest animal inhabitant and it is astonishing to imagine a life that began before Mozart and the French Revolution ending with an announcement on CNN. Tortoise longevity is driven by a slow reproductive hit rate. Giant tortoises are big, cold-blooded herbivores, with a sluggish metabolism. It takes them at least thirty years to reach sexual maturity and although, as adults, they have few natural predators, their young are not so lucky. Even the isolation of an island is no protection: only one egg in ten makes it to adolescence. So, a long life means a much better chance of passing on the genes.

TORTOISE DINGHY

The origins of giant tortoises stretch back fifty million years, to the time when the first turtles hauled themselves on to the land. They were able to exploit the niches left behind by large plant-eating dinosaurs and, predictably, started to grow large. One giant tortoise,

Colossochelys atlas

, was the size of a small car and spread across the globe, even colonising Antarctica. But the combination of a cooling climate and human ingenuity condemned them (the shell is an effective barrier to teeth and claws, but becomes an all-in-one cooking pot on a fire). By 1750, when Adwaitya emerged blinking from his shell, there were no continental giant tortoises left, but 250 species basking happily on their predator-free

islands. Today, there are only twelve species, all but one of them endangered.

Giant tortoise oil was

considered so delicious

that it was the only way

of making the flesh of

the dodo â called the

âdisgusting bird' by the

Dutch â palatable

.

Giant tortoises' heads gradually grew too big to be withdrawn into their shells â they had survived for so long without attack that even this protection deserted them. They also suffered the misfortune of tasting delicious. Although Darwin â whose theories of natural selection owed so much to the Galápagos species â thought them âindifferent' eating, most early accounts were ecstatic. One giant tortoise would feed several men, and both its meat and its fat were perfectly digestible, the liver was a peerless feast and the bones were rich with gorgeous marrow. Then there were the eggs: the best eggs anyone had ever eaten. Even more useful to sailors, the tortoises could be taken alive on board ship and survive for at least six months without food or water. Stacked helplessly on their backs, they could be killed and eaten as and when necessary. Better still, because they sucked up gallons of water at a time and kept it in a special bladder, a carefully butchered tortoise was also a fountain of cool, perfectly drinkable water.

Unsurprisingly, it took 300 years after its first discovery for the giant tortoise to receive a scientific name: the specimens were all eaten before they got back to the scientists. Worse still, large-scale commercial whaling in the nineteenth century was only made possible because the giant tortoises enabled ships to stay at sea for weeks at a time. One ship's log records âturpining' parties taking 14 tons of live tortoises on board one ship in four days.

If there is a glimmer of hope it concerns Adwaitya's descendants. In 1875, the government of Mauritius, inspired by Albert Gunter of the British Museum, declared

Geochelone gigantes

the world's first protected species. There are now 152,000 Aldabras â 90 per cent of the world's total giant tortoise population â happily isolated from their only serious threat: us.

O

ne of the odd things about the great apes â our closest primate relatives like the chimpanzee and the gorilla â is that their vocal communication is relatively unsophisticated compared to our own.

Not so the thirteen species of gibbons that live in the tropical forests of South-East Asia. Gibbons aren't monkeys â they don't have tails or cheek pouches â but âlesser apes', and their calls are some of the most beautiful and idiosyncratic sounds made by any animal. Gibbons use these calls to communicate precise messages, assembling elements of each call into a string which has a meaning that is understood by other gibbons in their family group, who use a similar sequence in return. Linguists call this âsyntax' â the linking of sounds in a particular way to create meaning â and it is the basis of all language.

KING OF THE SWINGERS

The development of this language may be linked to the fact that gibbons â unlike most other monkeys and apes â are monogamous. Like songbirds, gibbons sing to attract and keep a mate and to mark their territory, particularly their favourite fruit trees. To snag the best female to breed with, a male gibbon has to work on his singing. For females, the better the singer, the better the genes, and the more regular the supply of fruit.

Couples sing to each other every morning in fabulously complex duets. Males sing before dawn, sometimes

while still in âbed', which for a gibbon means sitting high up in the branches, with their arms hugging their knees and their heads tucked into their laps. Females are much more active and dramatic, breaking branches, leaping and climaxing with a sequence called the âgreat call'. Males who have a mate sing more regularly when there are rogue males sniffing around, as you'd expect.

Most family groups comprise a male and female living with three or four offspring, some of whom don't leave home until they are ten years old. Because of their energy-poor diet â fruit, leaves, and the occasional insect â families spend half their time just hanging around grooming one another. The female rules the roost at home; the males are right at the bottom of the hierarchy, even below the offspring. In some species the male takes over childcare once the young are weaned, teaching them how to swing.

No one knows how the

gibbon got its name. The

French naturalist Buffon

coined it, maybe as a

version of âgibb', the old

name for cat, or in honour

of his friend Edward

Gibbon, the historian

.

Gibbons are built to swing. Their arms are longer than their legs and bodies combined, and strong enough to propel them at speeds of 35 mph and across 50-foot gaps between trees. Their wrist bones are separated by soft pads which allow movement in all directions. This enables them to swing and change direction without having to turn their bodies â saving energy and giving them the breathtaking agility for which they're best known. On the rare occasions they walk on the ground, gibbons are bipedal, which has led researchers to propose that walking on two feet might originally have developed as an unforeseen by-product of arm-swinging in the canopy.

In Thai mythology, gibbons are the reincarnated souls of lost lovers. In one story, a woman searching for her murdered husband wanders the forests to this day repeating the gibbon's plaintive song, â

Pau! Pau!

' (Thai for âhusband').

T

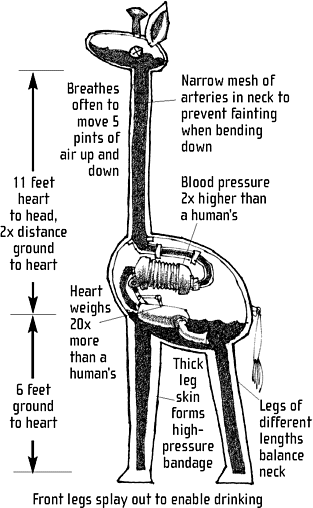

he ability to reach the leaves at the very top of trees seems reason enough to grow a long neck, but a giraffe's neck is about more than just food. Male giraffes use their necks as weapons and as signs of their virility. There's nothing cute about ânecking' between male giraffes; they lock them together like arm-wrestlers or swing their heads like medieval maces, with a terrifying force that can topple or kill their opponents with a single blow (a giraffe's skull weighs more than a full-size boxer's punchbag and sports up to five skin-covered horns called

ossicones

). Unlike the female's, the male giraffe's neck and skull continue to grow thicker throughout its life. The bigger the neck, the more victories, and the greater number of willing females that come flocking. To counter-balance the weight of these heavy-duty sex toys, the giraffe's neck has evolved with one more vertebra than other mammals, at the point where it joins the chest.

MORE THAN JUST A LONG NECK

The other key weapon in a male giraffe's lady-killing armoury is his odour: downwind you can

smell one from over 800 feet away. Early explorers compared their scent to âa hive of heather honey in September', but the key chemical constituent is indole, the nitrogen compound that gives our faeces their characteristic smell. As well as driving females wild, giraffe-pong has a practical function, acting as an inbuilt parasite repellent and killing many of the microbes and fungal organisms that graze on a giraffe's skin. Giraffes even secrete the active ingredient in creosote to kill bloodsucking ticks. As far as they are concerned, smelling bad means you are clean and healthy.

Most of a giraffe's life is spent either eating or chewing the cud. Their favourite meal is the acacia tree, which is so thorny that most other animals leave it alone. The top joint of their neck allows them to raise their heads vertically in line with the neck and browse for the young thornless leaves at the very top. Amazingly, the trees have learned to fight back by releasing a chemical that turns their leaves bitter. They also release a wind-borne âwarning burst' to alert surrounding trees to do the same. Giraffes, in turn, always try to approach acacias upwind.

The Romans

exhibited giraffes in

their amphitheatres

as âcamelopards',

assuming they were

a cross between

camels and leopards

.

Next to the neck, the other essential device is the tongue, which can extend up to 20 inches, long enough to clean their ears. A grasping tool with the same level of dexterity as three human fingers, a giraffe's tongue is used so often that it has taken on a blue-black colour to reduce the risk of sunburn.

Giraffes need less water than camels, and as acacia leaves are 70 per cent water, they rarely need to drink. This is good news, because their awkward splayed pose at a waterhole leaves them vulnerable to lions and crocodiles. The only time they kneel is to sleep, laying their head on the ground for ten minutes each day and, even then, keeping half their brain awake.

Giraffes are often hunted for their tail tuft which, at over 3 feet, is among the longest hair found on any mammal. It is used for bracelets and as an unofficial currency in Sudan and Uganda.