The Book of Animal Ignorance (18 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

W

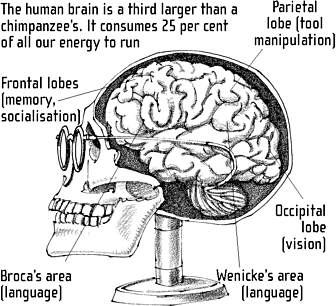

hat Darwin suspected, our DNA has confirmed: we are remarkably similar to our primate cousins â we share about 97 per cent with gorillas, and over 98 per cent with chimps, although the developmental difference those very particular genes makes is clearly evident. (Interestingly we are âhairier' than chimps, having more follicles, but their hair is thicker and longer.) The physiological differences are small: our hands are able to make two grips that a chimp can't; from this one modification all our manual dexterity has flowed. Combined with a gradual preference for walking on our hind legs (which still causes us physical difficulties), it's not impossible to see how freeing our hands also freed our minds. There is strong evidence pointing to language â the greatest of all tools â having evolved as gesture before it became speech. Culture started with our hands as well as our brains.

Human beings,

who are unique

in having the

ability to learn

from the

experience of

others, are also

remarkable for

their apparent

disinclination to

do so

.

DOUGLAS ADAMS

Why did it take us so long after we had grown our large brains and smart hands to start daubing walls, carving objects and telling stories? No one knows for sure what caused the so-called âgreat leap forward' but the astonishing homogeneity of

Homo sapiens

's DNA suggests that humans went through an ice-age âbottleneck' around 70,000 years ago, with our population being reduced to a few thousand individuals. Life must have been tough for a long time but gradually as these pockets of humans interacted and grew larger, social relationships would have developed, tasks would have been shared and campfires lit. Among monkeys and primates, a larger social group leads to greater intelligence. Imitation, communication, learning, problem-solving are all products of primate social interactions. Among humans, it

seems reasonable to suggest that these interactions selected for language. It's a self-reinforcing cycle: once it starts, it snowballs.

WHERE ALL THE TROUBLE STARTED

And where has the great leap taken us? We have jumped free of evolution. If we were to live in tune with the distribution curves that apply to other species, our total population would be fewer than a million. If we used primates as a guide, our communities would each be 150 individuals: large enough for breeding, small enough for there to be there are no strangers, with little crime or cheating.

But we human primates have used our brains and hands to transform the world, before our DNA could change us. We have swapped biology for history, nature for technology. The fact that you're reading this book is singularly extraordinary. You have learned a complex language, and can interpret meaning in its written form. But now this very ingenuity is creating its own limits. The animals and plants we have domesticated are so lacking in genetic diversity they are falling prey to new diseases. Globalisation means that at any one time half a million people are in the air, and millions more are on the move, their bodies and suitcases full of organisms hungry for fresh habitats. Cities â our greatest invention â are choking the planet's skies and threatening the delicate balance of climate which makes life possible.

All human cultures tell the same stories â of the man punished for stealing fire; of the flood that sweeps away all we have built. Only stories, and the imagination that feeds them, may be strong enough to save us from the endless ingenuity of our hands.

T

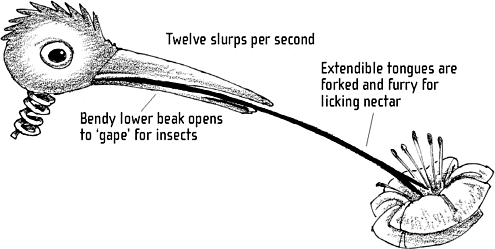

he smallest bird of all is the bee hummingbird (

Mellisuga helenae

) and it weighs less than a penny. Despite being not much more than feathered wing muscles, the 320 species of hummingbird carry a huge amount of cerebral firepower. Relative to body size, their brains are twice as large as our own and this helps them do a number of things beyond the scope of larger animals.

LICKING NOT SUCKING

Like us, they have a precise sense of time. The Rufous hummingbird (

Selasphorus rufus

) remembers not only where its food is located, but also when it last fed there. It will leave flowers enough time to fill up with nectar before revisiting them. Hummingbirds are also one of only six groups of animals that learn how to communicate vocally, rather than just through instinct. Humans, whales and bats do this, but among other birds, it is only the parrots and songbirds that learn by imitation. Special structures in the frontal lobes of the brain control vocal learning, and this skill seems to have evolved independently in all three bird groups. For hummingbirds, it is driven by the need to maintain strict territorial control. Their nectar-licking lifestyle requires so much energy that keeping the neighbours away from the food supply is essential to survival. Singing is the most efficient way of doing this.

Their unique ability to feed from flowers while hovering also requires special brain adaptations. They can see much further

into the ultraviolet spectrum than other birds (perhaps to help with flower recognition) and have a large section of brain dedicated to the visual adjustment that allows them to focus, despite the airflow created by having wings that beat up to 200 times a second. This also creates astonishing physical demands, so as well as being clever, hummingbirds have the largest heart relative to size, and the fastest metabolism, of any animal. In a single minute, their hearts can beat up to 1,200 times and they may take as many as 500 breaths.

The craze for hummingbird

âskins' for hats and bags

peaked in the late nineteenth

century: one London

dealer imported over

400,000 in a single year.

Many unrecorded species

were hunted to extinction

until it was finally made

illegal in 1918

.

Their flying technique is closer to a bumblebee's than to that of other birds, with ball-and-socket shoulder joints allowing their wings to rotate 180 degrees in all directions. As they hover the wingtips move horizontally, tracing a figure-of-eight pattern rather than up and down, as with most birds. This means they can generate lift on both strokes, enabling them to fly forwards, backwards, and even upside down. To keep this up, they need to eat at least their own body-weight in nectar (for energy) and insects (for protein) every day. That means visiting an average of 1,500 flowers. Because this generates so much liquid waste, hummingbirds are continually dripping urine.

Their tiny feet are useless on the ground so they spend three-quarters of the day perching to save energy. At night, some species go into an energy-efficient torpor â a kind of mini-hibernation â where their metabolism plummets and their body temperature almost halves.

Hummingbird feathers come in two basic colours: reddish-brown and black. The amazing range of colours we see is caused by granules of melanin and tiny air bubbles in the feathers that refract light to create a metallic sheen. Light must shine on an iridescent feather at the correct angle, or we only see the dull âpigment' colours.

T

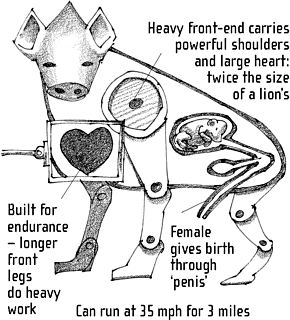

he female Spotted hyena (

Crocuta

crocuta

) carries something between its legs that continues to baffle and fascinate biologists: a clitoris that matches the male's penis in shape, size and erectness. Its vagina is fused shut, so it uses this one organ to urinate, mate and give birth. How and why it has evolved may seem hard to fathom, not least because giving birth often results in painful tearing which kills one in ten mothers and often suffocates the first-born cub, whose umbilical cord is too short to negotiate the elongated birth canal. The usual assumption is that testosterone âleaks' from male siblings in the womb, dousing the females, as sometimes happens to produce âbutch' female mice. But there is little evidence for this in spotted hyenas, and all females are similarly endowed.

The ancient Egyptians

trapped hyenas as pets

and fattened them for

the table. In the

Ethiopian city of Harar,

âhyena-

men' still feed

on wild hyenas at

dusk, holding the meat

in their mouths

.

The key is social organisation. Hyenas live in female-dominated societies, where every member in a clan has a precise hierarchical rank, with females being senior to males, and the female rank being inherited through the mother. This matriarchal social structure rivals those of the higher primates in complexity. In hunting terms, it delivers numerous benefits. A clan will chase their prey for miles, if necessary, until the target animal simply gives up. At that point the hyenas tear into its belly and legs, starting to eat it while it is still alive. This requires co-ordination and planning, but, above all, tremendous aggression. That's where the testosterone comes in handy. From birth, spotted hyenas are programmed to fight and a cub will often kill its twin (they are born in pairs) to establish dominance.

Spotted hyenas are Africa's dominant predator, responsible for

a quarter of all game animals killed. Lions are their only rivals and the two species exist in a constant state of war. Both steal food from each other, but contrary to popular belief, lions scavenge more often from hyenas. In many areas, hyena kills are a lion's main source of food. Hyenas eat fast, and they eat a lot â a third of their own body-weight, or the size of large lamb, in just half an hour. They devour everything: the concentrated hydrochloric acid in their guts digests even the skin and bones, leaving their scat white with calcium.

For centuries, hyenas have been feared as corpse-eating grave robbers, sexual perverts and cowards. This human dislike of hyenas has ancient roots. The earliest hominid remains in northern Europe from 700,000 years ago are usually found close to hyena-gnawed bones and fossilised droppings. Whether as scavengers or as hunters, our species has evolved in close competition with hyenas.

Their eerily human-sounding âlaugh' is really a signal of submissiveness to clan superiors. Hyenas also whoop, to communicate over long distances. It's often the laugh or whoop which alerts other animals to come and poach their kill. At least one study has suggested that human music began with the collective hunting chants our ancestors used to âoutsing' the ancient enemy.

LONG-DISTANCE KILLER

Hyenas aren't related to dogs: their closest relative is the cat-like civet. All four modern species, including the termite-eating aardwolf, are endangered through habitat loss and persecution by superstitious humans.