The Book of Animal Ignorance (31 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

I

f spiders didn't exist, we'd have to invent them; without them, we'd simply drown in insects. Until the late eighteenth century, we just assumed they

were

wingless insects, but they now have their own class,

Arachnida

, which contains 40,000 identified species, with as many again waiting to be named. They were one of the earliest land animals to evolve and are predatory, territorial carnivores: put 10,000 spiders in a sealed room and you will eventually end up with a single fat spider. The mass of insects eaten by British spiders in a year outweighs the UK's human population. And by âeat' we really mean drink: they dissolve their victims first.

The tarantula's bite

was supposed to bring

on extraordinary

symptoms: stupor,

involuntary erections

and an uncontrollable

desire to dance off the

venom in a violent and

energetic dance (the

âTarantella') for over

three days. It turns out

it was another spider's

bite that brought on

these symptoms

.

That's an impressive trick, but not unique to spiders. What spiders do best is spin webs. Spider's silk is five times stronger than steel and thirty times more stretchy than nylon. It is so light that a strand long enough to circle the world would weigh the same as a bar of soap. It is made from protein strands and water spun together; the protein gives it strength, and the surface tension of the water lends it elasticity â but we still don't really understand how it's done. An average spider will spin more than 4 miles of silk in a lifetime, and this can be collected and woven into garments. However, their predatory nature makes them tricky to farm, so we will have to wait for genetic engineering to deliver spider-silk parachutes, bullet-proof vests and artificial tendons.

Some spiders use their webs to fly. Called âballooning', it involves them climbing to the top of a fence, pointing their

backsides into the air, squirting out a long line of silk and letting the breeze take them. They can travel immense distances and have been found as high as 16,000 feet. Spiders can create perfect webs almost anywhere, even in zero-gravity, but give them drugs and they lose the plot. In 1995, a NASA experiment revealed that marijuana made them lose concentration halfway through spinning, whereas amphetamines made them spin quicker but much less accurately. Caffeine was the most extreme: the coffee web consisted of a few threads randomly strung together.

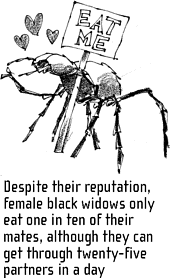

Male spiders don't have a penis. To mate they ooze drops of sperm on to a special sperm web. They then suck this up into one of a pair of specially adapted legs, called âpedipalps'. The pedipalps insert, twist and lock it into the corresponding female slots and pump in the sperm, rather like R2D2 uploading into a mainframe. Often the end snaps off on completion. Inserting these pedipalps can be a perilous business for the male: his partner can be a hundred times his size. In one species, the Tent cobweb weaver (

Tidarren sysiphoides

), the male chews off one of his pedipalps beforehand to gain a speed and mobility advantage over the other suitors. He usually dies on the job, his dead body keeping his sperm safe from competitors for several hours. The male Australian redbacks (

Lactrodectus hasselti

) actually compete to be eaten. Being devoured by the female ensures that their pedipalp gets in first.

Although spiders are surrounded by fear and superstition, humans do sometimes eat them. The Piaroa people of Venezuela consider the world's largest spider, the Goliath bird-eating tarantula (

Theraphosa

leblondi

), a delicacy. Roasted, they yield a quarter-pound of prawn-like white meat and are served with their fangs on the side, as toothpicks.

S

tarfish aren't fish; they are much older. The echinoderms (âspiny skins'), which also include sea urchins and sea cucumbers, first appeared in the early Cambrian period, about 550 million years ago, and haven't changed much since. Unlike molluscs and insects, they have an internal skeleton made from plates of calcium carbonate called

ossicles

. This makes them the direct relative of all vertebrates, including humans.

They don't have a central brain, but being star-shaped, they don't have a âfront' or âback' either. The nearest they get is a ring of nerves that runs round their mouth. From this an individual nerve runs down each leg. As one leg moves â usually the one closest to food â it lets the others know to follow it. A splendid advantage to this system is that starfish can regenerate lost limbs, and in the case of the

Linckia

species, the lost limbs can even regenerate a new starfish. The early stages of this process â one large arm, a tiny body and four tiny arms â look like small seaborne comets.

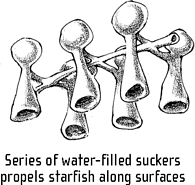

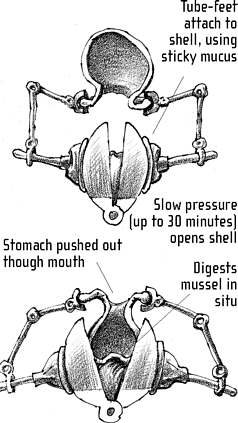

Starfish have a mouth (underneath) and an anus (on top) but they arrived a long time before ears, eyes or noses. Instead, they have hundreds of multi-tasking tube-feet covering their underside. They use these to breathe, to move and to attach themselves to prey. They also function as noses, assisted by the skin's sensory cells (2.6 million per square inch), responding to chemical changes in the water around them, and locking on to âodour plumes' given off by potential food. At the tips of the legs, âeyespots' (which may be mutated feet) act as light sensors.

In business jargon, a

âstarfish' organisation

is completely decentralised.

On the

other hand, passive

sexual partners are

sometimes described

as starfish because

they âjust lie there'

.

Starfish move using simple hydraulics. They take in seawater through a special sieve-like opening called a

madreporite

and distribute it internally to all the feet-tubes. By squeezing and sucking water in and out of the feet in sequence, they can move surprisingly quickly. Some species manage three feet a minute.

Starfish sex is a strictly arm's-length business. Each leg contains a large sex organ, but short of dissecting them it is impossible to tell male from female. They gather in groups when spawning, the male releases sperm into the water if he detects eggs; the female releases up to two and half million eggs at a time if she detects sperm. The larvae are completely unlike their parents and look more like free-swimming plankton. Eventually they grow arms, sink to the bottom and stick to a rock, before metamorphosing into adults.

THE

STARFISH

DINER

Fully-grown starfish have few predators; their spiny skin is covered in tiny pincers which nip at anything that annoys them. They also âgroom' the skin, keeping it clear of parasites. One species,

Luidia

, just disintegrates into fragments if it gets caught.

Starfish eat almost anything too slow to escape, particularly mussels and oysters. A square-mile army of starfish was recently sighted off Le Morbihan in France, at a density of fourteen to the square foot, moving slowly across the ocean floor and consuming everything in its path.

W

hen Stanley Kubrick cast tapirs alongside early hominids in the opening sequence of

2001

:

A Space Odyssey

, it was because they seemed âprehistoric'. He was right: they may look like the result of a night of passion involving a pig and an anteater but tapirs are the last survivors of a large family of mammals that have changed little in twenty million years. At one point they were found on every continent (except Antarctica) but now there are only four species left: three in Central and South America and one on the other side of the world, in South-East Asia.

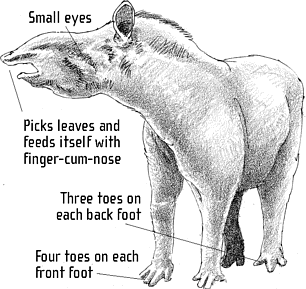

Tapirs are perfectly adapted to life in warm, wet forests. They can graze on the forest floor for fallen fruit and browse higher up for green twigs and ferns. Their stout bodies barrel through thick undergrowth at high speed and they are as happy in the water as on dry land. But the key to their early success remains their most distinctive feature, a short, multi-directional trunk â the ultimate accessory for forest life. It gave them greater reach when feeding, functioned as a snorkel for travelling under water, and provided a continuous olfactory read-out on the presence of food, or the possibility of sex.

FOURTEEN TOES

AND ONE FINGER

But the climate has changed, and cooler, drier conditions have seen forests replaced by grassland, which favours grazing ruminants, not shortsighted, semi-aquatic fruit-chewers. Unlike

their closest relatives, horses and rhinos, tapirs haven't managed this transition, and now all four surviving species are endangered.

As well as the loss of habitat, tapirs are also threatened by human predation. Hundreds are poached each year for their fatty meat (often sold as buffalo), their durable hide (

tapira

is a Brazilian Indian word for âthick') and the various parts of their anatomy still used as folk cures for heart disease and epilepsy. In many Amerindian tribes, the Milky Way is known as the âTapir's Way', in the same way the American Plains Indians call it the âPath of the Buffalo'. In China and Japan, their name means âdream-stealer'.

The Thai word for tapir

is

P'som-sett,

which

means âmixture'. It

comes from the belief

that the tapir was

made from the leftover

bits of all the other

animals

.

Other than humans, tapirs are too strong and nimble to have many predators. Occasionally, a big cat will take one on, in which case the tapir simply leaps into a nearby stream and sinks until the cat is forced to let go. Tapirs like walking on the bottom of streams and ponds: it cools them down and allows fish to strip their hide of parasites.

Tapir calves look very different from their parents: they are striped and spotted, like furry watermelons. This provides surprisingly good camouflage in the dappled shade of the forest, but they still fall prey to the giant anaconda, which likes to swallow them whole. Although we call their offspring âcalves', zoologists have now agreed that tapirs are sufficiently different from other hoofed mammals not to call the adults âbulls' and âcows'.

Tapirs are the least well-studied of all large mammals. We don't know whether they mate for life, how their family groups work, where they sleep, or the function of their strange bird-like whistles. But this is changing. Their importance in the ecosystem of the rainforest has made them a conservation landmark species. Just as they need the forest to survive, so many of the forest fruiting plants depend on the tapir's digestive tract to propagate. Saving the tapir will help save the rainforest, too.