The Book of Animal Ignorance (33 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

M

ost species described as âliving fossils' struggle to fully justify the claim but not the tuatara. This ancient reptile looks like an iguana, but it isn't a lizard. Nor is it a dinosaur, although it has changed little since the days of the giant reptiles. It's a

sphenodon

, or âwedge tooth', the last member of an order that once covered the planet. The tuatara has survived for two reasons. Firstly, it happened to find itself on the small land mass that became New Zealand about eighty million years ago, as it split from Gondwanaland, the southern super-continent, before mammals had established themselves. And second, it found a way of adapting to a colder climate.

Most of the sphenodons disappeared with the dinosaurs; those that didn't got hustled out of their niches by mammals. The tuatara ploughed its own furrow quite happily for millions of years, until the mammals finally reached them, paddling canoes. With the canoe-mammals came others, most notably dogs and rats. The tuataras were gradually driven from the mainland and now survive only on islands dotted around New Zealand's coast.

Tuatara means âspiky

back' in Maori. The

Maori once ate them but

only the men â a woman

who broke the rule

risked being pursued

and killed by the entire

tuatara population

.

Their main disadvantage in the battle with mammals is metabolism. Tuataras are the most primitive of all living reptiles. Their brain is tiny, more like an amphibian's than a lizard's. Their heart and circulatory system are also rudimentary, making them extremely cold-blooded, and they live on islands which are often wind-battered and chilly. Out of necessity, âdo it slowly' has become the tuatara's motto. They grow more slowly than any other reptile. It takes them fifteen years to reach sexual maturity and even then, the females only manage to produce a clutch of eggs every four years and they take

over a year to hatch. Their method of hunting is to sit outside their burrows at night waiting for beetles, worms, crickets, or â best of all â a young tuatara to toddle past. Their method of defence is to sit inside their burrow waiting for the danger to go away. That's no challenge for a sprightly rat. In 1981, the island of Whenuakura had a population of 200 tuataras. By 1984 they had gone, replaced by a colony of rats.

Several features set the tuatara apart from their lizard cousins. They can live for well over a hundred years. They don't have teeth but all-in-one serrated jawbones: in old tuataras these jaw âteeth' are worn smooth, leaving them to gum their way through slugs and earthworms. Also, unlike the doubly endowed lizards, tuataras have no penis: they reproduce by pressing their bottoms together, like birds and (probably) dinosaurs.

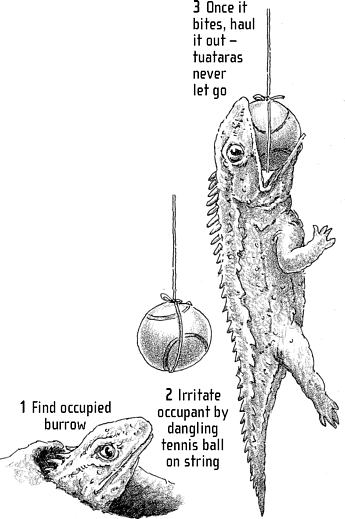

HOW TO CATCH

A TUATARA

Oddest of all is the third eye in the middle of their forehead. Although scales grow over it by the time they are six months old, it is a real eye with a lens, retina and a nerve connection to the brain. It appears to be light-sensitive and might help in regulating body temperature. Temperature matters to a tuatara: they live cheerfully in conditions that would trigger hibernation in most reptiles (10°C), so heat can kill them. Rising temperatures also pose a more serious threat. As with turtles and crocodiles, the sex of the hatchling is determined by the heat of the egg. The warmer northern colonies of the 55,000-strong tuatara population are now producing twice as many males as females.

T

he word âwalrus' may be from Dutch

walros

(âshore-steed') and its Latin name

Odobenus rosmarus

means âtooth-walking seahorse', but walruses look nothing like horses. They are almost as round as they are long; they have no visible ears and they drag themselves along by their teeth. They also change colour when heated, from off-white to pink to cinnamon brown. A beach heaving with basking walruses looks like a skip-load of deformed cocktail sausages.

The walrus in Lewis

Carroll's 1871 poem âThe

Walrus and the

Carpenter' was inspired

by a stuffed specimen in

Sunderland Museum, of

which only the head

remains. The poem, in

turn, inspired John

Lennon's acid anthem âI

Am the Walrus' on

Magical Mystery Tour

.

Walruses are inordinately fond of seafood. They enjoy cockles and mussels, crabs, shrimp, snails and octopus and can wolf down more than 6,000 clams in a single meal. Clams bury themselves in the seabed, so the walrus first has to unearth them. To do this, it brushes the sediment away with a flipper and it almost always uses the right-hand one. There are no southpaw walruses. It was long assumed that all animals are ambidextrous, but recent research has shown this is not so. As well as walruses, whales, chickens and toads tend to lead with their right, whereas frogs and lizards favour the left.

Another way that walruses feed is to create a high-pressure hose effect using their lips and tongues to blast the seabed and expose their lunch. This creates a thick murk of sand and debris, so, rather than using their small eyes to identify prey, they slide along feeling the bottom with their moustaches. These are composed of more than 400 incredibly sensitive whiskers, known as

vibrissae

, Latin for âvibrators'. A grazing walrus can move each of them independently.

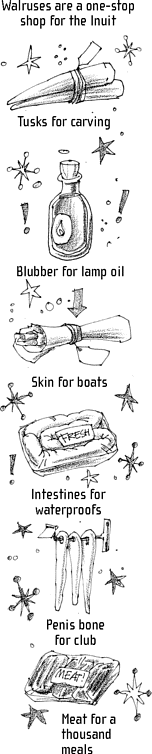

THE ARCTIC SUPERMARKET

Walruses suck as well as blow. When they find a clam, they hold it firm in their lips, create a vacuum around it and use their tongue like a piston to extract the soft tissue. As a special treat, they hoover up seagulls from underneath or suck the brains of seal pups out through their nostrils, a party trick also used by young Inuit in Greenland to impress tourists. Walruses have a sucking power three times stronger than the average Dyson, which explains why their stomachs are full of small pebbles.

Medieval merchants used to pass off walrus tusks as unicorn horns. They are canine teeth that never stop growing; in a large male they can be 3 feet long. Apart from helping them haul themselves on to ice floes, they are mostly for show. Walrus society is simple: the bigger the male, the more impressive the tusks, the more lady walruses make themselves available.

Mating among walruses is much like a sub-zero version of a Club 18â30 holiday. The females lounge provocatively on the ice, while being ogled by a pack of alpha-males bobbing around in the water, trumping, clacking, roaring, rasping and occasionally gouging chunks out of one another. Unlike those in Club 18â30, however, the female will only mate with one male. Walrus sex takes place underwater and it's impressive stuff. The male's penis contains a bone almost as long as its tusks, which guarantees fail-safe operation in even the coldest Arctic seas.

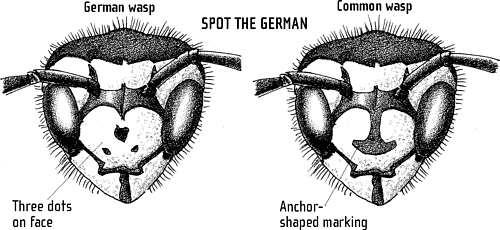

O

f the thousands of species of wasp out there, there are only two that regularly bother us: the Common wasp (

Vespula vulgaris

) and the German wasp (

Vespula germanica

). There's not much to chose between them: both live in colonies and fashion delicate spherical paper nests, both have a nasty retractable sting, both cause a huge fuss at late summer picnics. Wasps, of course, suffer the great misfortune of not being bees: they don't make us honey, their markings are stark and uncuddly and their behaviour seems thuggish in comparison to the mystical dances and complex social life of their furry cousins. This is unfair; for a start, bees are really just vegetarian wasps. Each of them has a job to do and without the voracious appetite of the wasp many insect pests would overrun our gardens.

The appetite is not quite what it seems. Like bees, most of the wasps we see are sterile females, but in spite of their impressive mouthparts, they have a very simple digestive tract, which means they can only eat sweet nectar. They kill and scavenge tirelessly, but not for themselves. Their jaws are used to chew up protein for the endlessly hungry larvae back at the nest. Then, in return for bits of bacon sandwich or beetle, they get a blob of sweet, nutritious âsoup' from the larva's mouth. But at summer's end, this food source runs out. Its breeding work done, the commune disperses; next year's queens find a sheltered place to spend the winter, while everyone else gradually dies off. This is when worker wasps â now unemployed and unfed â become a nuisance to humans. In the last few, purposeless weeks of their lives, before cold weather finishes them off, they seek alternative sources of sugar, in our kitchens, orchards and picnics. It's now that most humanâwasp interaction occurs â sometimes with fatal consequences, for wasp and human.

Often these interactions culminate in one of the humans

claiming they are being attacked by a âhornet'. The hornet (

Vespa

crabro

) is the largest and noisiest of the European social wasps, which no doubt explains why people have long been terrified of it. But, in fact, its sting has much less effect on humans than that of a bee. Bees have evolved their venom as a defence against honey-stealing vertebrates, including beasts the size of bears and badgers, whereas a hornet's poison is intended mainly for use on its invertebrate prey. Analysis of hornet venom suggests that a fatal dose for a human (unless he was allergic to it) would be something like a thousand stings.

It's a bad idea to kill a

wasp: dying wasps

emit a pheromone that

alerts its nest-mates

to danger, so you may

be surrounded within

seconds

.

There is an important exception. The Asian giant hornet (

Vespa

mandarinia

) of Japan, also known as the yak-killer, is the super-predator of the wasp family. They are enormous â like flying thumbs, with a quarter-inch sting. They are fast, strong and merciless â ten of them can take out an entire honeybee colony in a matter of hours, tearing off the bees' heads with their terrifying jaws. Their venom is strong enough to dissolve human tissue and they kill over fifty people a year. But the Japanese get their own back in style: they serve the larvae raw as hornet

sashimi

and deep-fry the adults, which are reputed to taste like sweet prawns.