The Book of Animal Ignorance (3 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

A

nts boggle the mind. In the jungles where three-quarters of them live, they teem 800 to the square yard, 2.4 billion to the square mile and collectively weigh four times more than all the neighbouring mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians put together. The 12,000 named ant species come in all shapes and sizes: a colony of the smallest could live happily inside the braincase of the largest. Like bees and termites, their success flows from their social organisation, but there is nothing remotely cuddly about ants: they are the stormtroopers of the insect world, their ruthlessly efficient colonies operating like a single âsuper-organism'.

EARTHSCRAPER

Every process within an ant colony is regulated by chemicals. In some species, this can be refreshingly direct: the queen will climb to a high point when she is ready to mate, then stick her backside in the air and release a love-pheromone that inflames the ardour of all males in range. Ant species mate in a variety of different ways: in mid-air, on the ground or in a âmating ball', where the queen is completely surrounded by a swarm of love-addled males.

As well as love charms, pheromones also act as air-raid sirens.

If the colony is threatened, many species emit a pheromone from a gland in their mouths. This causes some workers to grab the larvae and run underground while others prance around with their mandibles open, ready to bite and sting. Brunei ants even have guards that explode their own heads when threatened, leaving a sticky mess which slows down the intruders.

Harvester ants eat

more small seeds

than all the

mammals and birds

put together. Like

squirrels, they often

forget where they've

put their stashes, so

are accidentally

responsible for

planting a third of

all herbaceous

growth

.

Inter-species warfare is common and ant raiders will take hostages back to their own colony, where they become slaves. Other species use this to their advantage: the queen of

Bothriomyrmex decapitans

allows herself to be dragged to the nest of rival species, where, like a mini-Trojan horse, she bites off the head of the host queen and begins laying her own eggs. Being ants, the host workers switch loyalty without batting an antenna.

Some ants raise livestock. They collect the honeydew made by aphids and in return protect them from other predators. The ants âmilk' the honeydew by gently stroking the aphid's abdomen with their antennae. Meanwhile, more than 200 species of ant are arable farmers, farming fungi for food. They gather compost for it to grow on, fertilise it with their dung, prune it and even fumigate it with powerful bacteria to keep it parasite-free.

But for all their awe-inspiring industry and adaptive élan, ants don't get it all their own way. The South American bullet ant (

Paraponera clavata

) is one of several species that finds out too late that fungi can sometimes farm them. Spores from a

Cordyceps

fungus work their way inside the ant's body and release an âoverride' pheromone which scrambles its orderly world. Confused and reeling, it finds itself climbing to the top of a tall plant stalk and clamping itself there with its jaws. Once in place, the fungus's fruiting body erupts as a spike from the insect's brain and sprinkles a dust of spores on the ant's unsuspecting sisters toiling below.

I

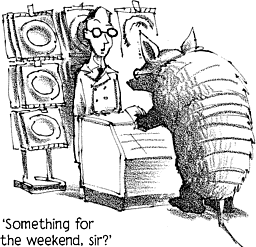

f the male Nine-banded armadillo (

Dasypus novemcinctus

) were human, its penis would be 4 feet long. When you're making love to something that resembles an upturned fishing dinghy, size matters.

Describing armadillos has always been a challenge: the Aztecs called them

azotochtli

, âturtle rabbits'.

All twenty species live in the Americas. The smallest is the Pink Fairy armadillo (

Chlamyphorus truncatus

), which is no longer than a sausage and looks like a furry prawn. The Screaming Hairy (

Chaetophractus vellerosus

) armadillo squeals like a pig when disturbed, though this seldom happens: it spends seventeen hours a day asleep and often won't wake even if you pick it up or hit it with a broom.

During the Great

Depression in 1930s

America, hungry people

resorted to baking

armadillos. They were

nicknamed âHoover Hogs'

as a dig at President

Herbert Hoover

.

The Giant armadillo (

Priodontes

maximus

) weighs up to 135 lb (heavier than most Texan cheerleaders), sports lethal 9-inch claws and has the largest number of teeth of any mammal: a hundred tubular pegs that never stop growing. The Three-banded armadillo (

Tolypeutes

tricinctus

) is the only one that can roll into a ball.

Nine-banded armadillos (despite the handicap of having wedding-tackle big enough to scratch their own chin with) are strong swimmers. They swam the Rio Grande in 1850 and spread to most of the southern United States where

there are now between thirty and fifty million of them.

They have two ways of getting across rivers. Their bony armour means they naturally sink, so they can just stroll along the bottom, holding their breath for up to six minutes. If they need a longer swim, they gulp down air and inflate their stomachs into life-jackets.

The poet Dante Gabriel

Rossetti kept a pair of

armadillos as pets in his

back garden in Chelsea.

One of them burrowed its

way into his neighbour's

kitchen â its head

appeared from under a

hearthstone and convinced

the cook that she had been

visited by the Devil

.

Males mark their territory with urine and their smell has been likened to that of an elderly blue cheese. To avoid giving birth in the winter, females can hang on to a fertilised egg for up to two years.

Other than humans and mice, Nine-banded armadillos are the only animals seriously afflicted by leprosy: most armadillos in Louisiana are lepers.

In next-door Texas, armadillos are one of two state mammals â the other is the Texas longhorn. They've also been nicknamed the âTexan speed bump'. Their singularly ineffective defence mechanism is to leap several feet in the air when startled: Texan highways are littered with them.

As a result, armadillos lead the world in research into the function of the mammalian penis. The members of dead armadillos are regularly harvested from road-kill â a job made easier by the fact that they are so gigantic.

Armadillos have been around for sixty million years: they are almost as old as the dinosaurs. In Bolivia and Peru, their shells are made into mandolins called

charangos

in imitation of Spanish guitars. They are then fitted with ten strings, generally tuned to A minor â a sad and noble key.

T

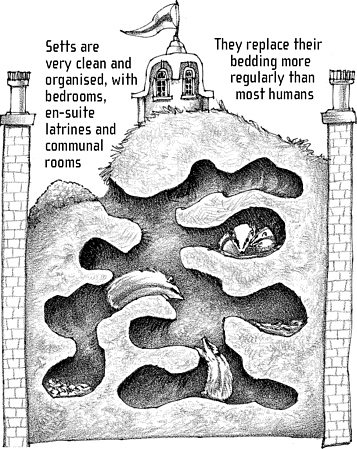

he parallels with the British upper classes are striking: badgers are stubborn creatures of habit; some of their setts, and the paths or âruns' that lead to them, are centuries old, handed down from generation to generation like stately homes. The largest sett ever found was a veritable Blenheim Palace with more than 130 entrances, fifty rooms and half a mile of tunnels. Seventy tons of earth had been moved to make it. Most setts house a group of up to twenty adult badgers, known as a âclan', and they will spend half their lives inside it, fast asleep.

BADGER HALL

Badgers are members of the Mustelid family, closely related to weasels and otters. âMustelid' comes from the Latin for weasel,

mustela

, itself from the word for, mouse, but badgers mostly feed on juicy earthworms, and very rarely need to drink as a result. If pushed, they will eat mice, as well as rats, toads, wasps, beetles, hedgehogs and even cereal crops.

Their stripe lets other species know that they are strong, fierce and ready to defend themselves. To communicate with their clan they produce a

strong âmusk' from glands under their tails. This is used for marking territory and establishing family identity. Each badger has its own unique scent and a âclan odour' made by the continual swapping of scent. Any adult that spends too long out of the sett risks rejection if his clan scent wears off. They have also evolved a vocabulary of sixteen different sounds, including churrs, growls, keckers, yelps and wails. Hearing the wail was once taken as an omen of impending death.

Badgers can mate at any time of year, and sex can last for up to ninety minutes. The sow will mate with several different boars, holding all the fertilised eggs until she gives birth to a multi-fathered litter in the early spring. Only 60 per cent of cubs will survive their first year of life. Most die by the time they are seven: 1 in 6 are killed on British roads each year.

Britain has the highest concentration of badgers of any country. Since 1985, the population has grown by 70 per cent to over 300,000, despite culling prompted by the belief that they spread tuberculosis to cattle. Paradoxically, culling badgers has the opposite effect. Since culling began in the 1970s, 59,000 badgers have been killed but more than 118,000 infected cattle have been slaughtered. This is because culling causes badger colonies to break up, forcing the infected survivors to move.

The European (or Eurasian) badger (

Meles meles

) spread into Europe from China two million years ago. They are still common there today. The hair for shaving-brushes originates on the backs of Chinese badgers, who are culled as an agricultural pest. Despite the myth, they are not shorn like sheep.

The origin of the word âbadger' is uncertain, but the best guess is the French

bêcher

, meaning âto dig'. The French call them

blaireau

, a word they also use for âshaving-brush' and âtourist' (because of the well-worn tourist âbadger runs').

Victorian gentlemen

used the badger's penis

bones as tie-pins

.

Badger meat was once eaten in both Ireland and Britain. Their hind legs were cured as âbadger hams' and tasted like well-hung mutton.