In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind (23 page)

Read In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind Online

Authors: Eric R. Kandel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

During our sojourn in France, Denise, Paul, and I visited Bar-le-Duc several times, and Elise, Lewis, and their children came to visit us in Paris. These visits gave us the opportunity to discuss Elise’s new faith in a more leisurely setting, and I gradually realized that she was searching for a deep belief. In time, Elise also converted their five children, to my mother’s deep dismay and my astonishment. Lewis, who had not converted, did not intervene.

By 1965 Lewis and Elise were eager to have their children grow up in the United States. Lewis arranged for a transfer to an air force base in Tobyhanna, Pennsylvania. Two years later he took an administrative position at the Health and Hospitals Administration of the City of New York. He spent the week in New York living with my parents and the weekend in Tobyhanna. In the meantime, Elise moved from being a Baptist to being a Methodist. In the ensuing decade she became a Presbyterian and finally, as I once humorously predicted to her, a Roman Catholic.

From a distance, this progression seemed a search for increasingly greater structure, greater security, by a person who must have been very frightened on a deep level and looked to Christianity to contain her fear. If Elise was frightened, however, it was not apparent to me. I was amazed by her own actions and even more upset by her conversion of the children. Nonetheless, I had gone to a yeshivah and had a vague sense of what a deep religious conviction might mean to someone.

Even more important, I was all too aware that we are all haunted by our own history, our unique problems, our personal demons and that those experiences and fears profoundly influence our actions. During the period we lived in France, my first extended stay in Europe since leaving Vienna in 1939, I was made acutely aware of my own demons. Even while enjoying a productive period of research and a remarkable range of pleasurable cultural experiences, I felt at times intensely isolated and alone. French society and French science are hierarchical, and I was a relatively unknown scientist at the bottom of the ladder.

The year before I went to Paris, I arranged for Tauc to come to Boston to give a series of seminars. He stayed at our house and we gave a welcoming dinner party for him. But once we were in France, the hierarchy kicked in. Neither Tauc nor any of the other senior people at the institute invited us or any of their other postdoctoral fellows to their homes or interacted with us socially. Moreover, I experienced a subtle degree of anti-Semitism—particularly from the technical people in the laboratory, the technicians and secretaries—that I had not experienced since escaping Vienna. My feeling of unease began when I mentioned to Claude Ray Tauc’s technician, that I was Jewish. He looked at me in disbelief and insisted that I did not look Jewish. When I assured him that I was, he quizzed me on whether I participated in the international Jewish conspiracy to control the world. I mentioned this remarkable conversation to Tauc, who pointed out to me that a good part of the French working class shared this belief about the Jews. This experience led me to wonder whether Elise, during her many years away from the United States, had encountered similar anti-Semitism and whether this demon might have contributed to her conversion.

In 1969 Lewis developed cancer of the kidney. The tumor was removed successfully, apparently without leaving a trace of the disease. Twelve years later, however, the cancer recurred without warning, tragically claiming Lewis’s life at age fifty-seven. After my brother’s death, my contact with Elise and the children, perhaps predictably, weakened significantly. We continue to see each other but now at intervals measured in years rather than weeks or months.

My brother is an enormous influence on me to this day. My interest in Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, and classical music in general, my love of Wagner and of opera, and my joy in learning new things were shaped to a great extent by him. In a later phase of my life, as I began to sense the pleasure of the palate, I came to appreciate that even here, in the area of good food and wine, Lewis’s efforts on me were not completely wasted.

IN OCTOBER

1963,

JUST BEFORE I LEFT PARIS, TAUC AND I HEARD

on the radio that Hodgkin, Huxley, and Eccles had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on signaling in the nervous system. We were thrilled. We felt that our field had been recognized in a very important way and that its very best people had been honored. I could not resist saying to Tauc that I thought the problem of learning was of such importance and still so untouched scientifically that whoever solved this problem might someday also get the Nobel Prize.

A

fter a very productive fourteen months in Tauc’s laboratory, I returned to the Massachusetts Mental Health Center in November 1963 as an instructor, the lowest rung on the faculty ladder. I supervised residents in training in psychotherapy, an exercise I called the blind leading the blind. A resident would discuss with me the various therapy sessions he or she had had with a specific patient, and I would try to give helpful advice.

Three years earlier, when I first arrived at the mental health center to begin my psychiatric residency, I had encountered an unanticipated bonus. Stephen Kuffler, whose thinking had so influenced my own, had been recruited from Johns Hopkins University to build up the neurophysiology faculty in the department of pharmacology at Harvard Medical School. Kuffler brought with him as junior faculty several extraordinarily gifted scientists who had been postdoctoral fellows in his laboratory—David Hubel, Torsten Wiesel, Edwin Furshpan, and David Potter. In one fell swoop, Kuffler had succeeded in forming the premier group of neural scientists in the country. Always a first-class experimentalist, he emerged as the most admired and effective leader of the American neuroscience community.

After my return from Paris, my interactions with Kuffler increased. He liked the work on

Aplysia

and was very supportive. Until his death in 1980, he proved a friend and counselor of immeasurable strength and generosity. He took an intense interest in people, their careers, and their families. Years after I had left Harvard, he would call on an occasional weekend to discuss a paper of mine he had found interesting or simply to inquire about my family. When he sent me a copy of the book he had written in 1976 with John Nicholls,

From Neuron to Brain

, he inscribed it, “This is meant for Paul and Minouche” (then fifteen and eleven).

DURING THE TWO YEARS I TAUGHT AT HARVARD MEDICAL

School, I struggled with three choices that were to have a profound effect on my career. The first arose when I was invited, at age thirty-six, to take on the chairmanship of the department of psychiatry at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston. The psychiatrist who had just retired from that position, Grete Bibring, was a leading psychoanalyst and a former colleague of Marianne and Ernst Kris in Vienna. A few years earlier, such an appointment would have represented my highest aspiration. But by 1965 my thinking had moved in a very different direction, and I decided against it, with Denise’s strong encouragement. She summarized it simply: “What, compromise your scientific career by trying to combine basic research with clinical practice and administrative responsibilities!”

Second, I made the even more fundamental and difficult decision not to become a psychoanalyst but to devote myself full-time to biological research. I realized I could not successfully combine basic research and a clinical practice in psychoanalysis, as I had earlier hoped. One problem I encountered repeatedly within academic psychiatry was that young physicians take on much more than they can handle effectively—a problem that only becomes worse with time. I decided that I could not and would not do that.

Finally, I decided to leave Harvard and its clinical environment for an appointment in a basic science department at my alma mater, New York University Medical School. There, I would start a small research group within the department of physiology focused specifically on the neurobiology of behavior.

Harvard—where I had spent my college years and two years of medical residency, and where I was then a junior faculty member—was wonderful. Boston is an easy place in which to live and bring up young children. Moreover, the university has extraordinary depth in most areas of scholarship. It was not easy to leave this heady intellectual environment. Nevertheless, I did so. Denise and I moved to New York in December 1965, a few months after our daughter, Minouche, was born, completing our family.

During the period in which I was working through these decisions, I was also in the process of terminating a personal psychoanalysis I had undertaken in Boston. Analysis was particularly helpful to me in that difficult and stressful period; it allowed me to dismiss ancillary considerations and focus on the fundamental issues involved in my making a reasonable choice. My analyst, who was extremely supportive, did suggest I consider having a small, specialized practice, one focusing on patients with a particular disorder, and see them once a week. But he readily understood that I was too single-minded at that point to carry off a dual career successfully.

I am often asked whether I benefited from my analysis. To me, there is little doubt. It gave me new insights into my own actions and into the actions of others, and it made me, as a result, a somewhat better parent and a more empathic and nuanced human being. I began to understand aspects of unconscious motivation and connections between some of my actions of which I was previously unaware.

What about giving up a clinical practice? Had I stayed in Boston, I might eventually have followed my analyst’s advice and started a small practice. That was still easy for me to do in Boston in 1965. But in New York, where few physicians were sufficiently familiar with my clinical competencies to refer patients to me, it would have been much more difficult. Moreover, one has to know one’s self. I am really best when I can focus on one thing at a time. I knew that studying learning in

Aplysia

was all I could handle at this early point in my career.

THE POSITION AT NYU, BEING IN NEW YORK CITY, HAD THREE

attractions that proved, in the long run, to be critical. First, it brought Denise and me closer to my parents and to Denise’s mother, all of whom were getting on in years, were having medical problems, and would benefit from our being nearby. We also thought it would be wonderful for our children to be closer to our parents. Second, while we were in Paris, Denise and I had spent many weekends visiting art galleries and museums, and in Boston we had begun to collect works on paper by German and Austrian expressionist artists, an interest that was to grow with time. In the mid-1960s, Boston had only a very few galleries, whereas New York was the center of the art world. Moreover, while in medical school I had followed Lewis’s lead and fallen in love with the Metropolitan Opera; the return to New York allowed Denise and me to indulge this interest.

In addition, the position at NYU gave me the marvelous opportunity to work with Alden Spencer again. After his stay at NIH, Alden had accepted a position as an assistant professor at the University of Oregon Medical School. He had become frustrated there because teaching was so time-consuming that it crowded out his research. I had tried without success to help him get a position at Harvard. The offer from NYU allowed me to recruit an additional senior neurophysiologist, and Alden agreed to come to New York.

He loved the city. It provided an outlet for his and Diane’s love of music, and soon after they arrived, Diane took up the harpsichord, studying with Igor Kipnis, a gifted harpsichordist who also happened to be a classmate of mine from Harvard. Alden occupied the laboratory next to mine. Although we did not collaborate on actual experiments (because Alden was working on the cat and I on

Aplysia

), we talked daily about the neurobiology of behavior and almost everything else, until his untimely death eleven years later. No one else influenced my thinking on matters of science as much as he did.

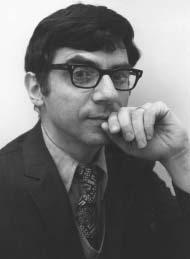

Within a year Alden and I were joined by James H. Schwartz (figure 12–1), a biochemist who had been recruited to the medical school independently of Alden and me. Jimmy and I had been housemates and friends at Harvard summer school in 1951, and he had been two classes behind me at NYU Medical School, where we renewed our friendship. However, we had not been in touch since I left medical school in 1956.

After graduating from medical school, Jimmy had obtained a Ph.D. at Rockefeller University, where he studied enzyme mechanisms and the chemistry of bacteria. By the time we met again, in the spring of 1966, Jimmy had established a reputation as an outstanding young scientist. As we talked about science, he mentioned that he was thinking of switching his research from bacteria to the brain. Because the nerve cells of

Aplysia

were so large and uniquely identifiable, they seemed like good candidates for a study of biochemical identity—that is, of how one cell differs from another at the molecular level. Jimmy began by studying the specific chemical transmitters used for signaling by different

Aplysia

nerve cells. He, Alden, and I formed the nucleus of the new Division of Neurobiology and Behavior that I had founded at NYU.

12–1

James Schwartz (b. 1932), whom I first met in the summer of 1951, obtained both an M.D. at New York University and a Ph.D. in biochemistry at Rockefeller University He pioneered the biochemistry of

Aplysia

and made major contributions to the molecular underpinnings of learning and memory. (From Eric Kandel’s personal collection.)

Our group was very much influenced by Stephen Kuffler’s group at Harvard—not just by what it had done, but also by what it was not doing. Kuffler had developed the first unified department of neurobiology that brought the electrophysiological study of the nervous system together with biochemistry and cell biology. It was an extraordinarily powerful, interesting, and influential development, a model for modern neural science. Its focus was the single cell and the single synapse. Kuffler shared the view of many good neural scientists that the uncharted territory between the cell biology of neurons and behavior was too great to be mapped and bridged in a reasonable period of time (such as our lifetimes). As a result, the Harvard group did not in its early days recruit anyone who specialized in the study of behavior or learning.

Occasionally, after he had had a glass or two of wine, Steve would talk freely about the higher functions of the brain, about learning and memory, but he told me that in sober moments he thought they were too complex to be tackled on the cellular level at that time. He also felt, unjustifiably I thought, that he did not know much about behavior and did not feel comfortable studying it.

Alden, Jimmy, and I differed with Kuffler on this point. We were not as constrained by what we did not know, and we found enticing the very uncharted nature of the territory and the importance of the problems. We therefore proposed that the new division at NYU examine how the nervous system produces behavior and how behavior is modified by learning. We wanted to merge cellular neurobiology with the study of simple behavior.

In 1967 Alden and I announced this direction in a major review entitled “Cellular Neurophysiological Approaches in the Study of Learning.” In that review we pointed out the importance of discovering what actually goes on at the level of the synapse when behavior is modified by learning. The next key step, we noted, was to move beyond analogs of learning, to link the synaptic changes in neurons and their connections to actual instances of learning and memory. We outlined a systematic cellular approach to this challenge and discussed the strengths and weaknesses of a variety of simple systems that lend themselves to such an approach—snails, worms, and insects, and fish and other simple vertebrates. Each of these animals had behaviors that, in principle, should be modifiable by learning, although this had not yet been demonstrated in

Aplysia

. Moreover, delineating the neural circuitry of those behaviors would reveal where learning-induced changes take place. We would then be in a position to use the powerful technique of cellular neurophysiology to analyze the nature of the changes.

By the time Alden and I were writing this review, I was already in transition not only from Harvard to NYU, but also from cellular neurobiology of synaptic plasticity to the cellular neurobiology of behavior and learning.

The impact of our review—perhaps the most influential one I have written—persists to this day. It inspired a number of investigators to take up a reductionist approach to the study of learning and memory, and simple experimental systems devoted to learning began to sprout up all over—in the leech, the snail

Limax

, the marine snails

Tritonia

and

Hermissenda

, the honeybee, the cockroach, the crayfish, and the lobster. These studies supported an idea, first put forth by ethologists studying the behavior of animals in their natural habitat, that learning is conserved through evolution because it is essential for survival. An animal must learn to distinguish prey from predators, food that is nutritious from that which is poisonous, and a place to rest that is comfortable and safe from one that is crowded and dangerous.

The impact of our ideas also extended to vertebrate neurobiology. Per Andersen, whose laboratory pioneered, in 1973, the modern study of synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain, wrote: “Did such ideas influence scientists working in the field before 1973? To me the answer is obvious.”