The Magician's Elephant

Read The Magician's Elephant Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

The Magician’s

Elephant

Kate DiCamillo

illustrated by

Yoko Tanaka

Table of Contents

A

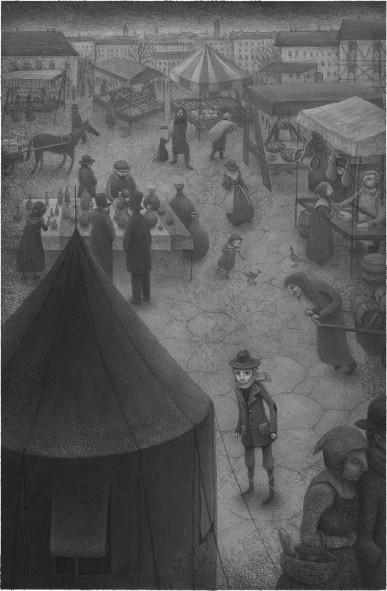

t the end of the century before last, in the market square of the city of Baltese, there stood a boy with a hat on his head and a coin in his hand. The boy’s name was Peter Augustus Duchene, and the coin that he held did not belong to him but was instead the property of his guardian, an old soldier named Vilna Lutz, who had sent the boy to the market for fish and bread.

That day in the market square, in the midst of the entirely unremarkable and absolutely ordinary stalls of the fishmongers and cloth merchants and bakers and silversmiths, there had appeared, without warning or fanfare, the red tent of a fortuneteller. Attached to the fortuneteller’s tent was a piece of paper, and penned upon the paper in a cramped but unapologetic hand were these words:

The most profound and difficult questions that could possibly be posed by the human mind or heart will be answered within for the price of one florit

.

Peter read the small sign once, and then again. The audacity of the words, their dizzying promise, made it difficult suddenly for him to breathe. He looked down at the coin, the single florit, in his hand.

“But I cannot do it,” he said to himself. “Truly, I cannot; for if I do, Vilna Lutz will ask where the money has gone and I will have to lie, and it is a very dishonourable thing to lie.”

He put the coin in his pocket. He took the soldier’s hat off his head and then put it back on. He stepped away from the sign and came back to it, and stood considering, again, the outrageous and wonderful words.

“But I must know,” he said at last. He took the florit from his pocket. “I want to know the truth. And so I will do it. But I will not lie about it, and in that way, I will remain at least partly honourable.” With these words, Peter stepped into the tent and handed the fortuneteller the coin.

And she, without even looking at him, said, “One florit will buy you one answer and only one. Do you understand?”

“Yes,” said Peter.

He stood in the small patch of light making its sullen way through the open flap of the tent. He let the fortuneteller take his hand. She examined it closely, moving her eyes back and forth and back and forth, as if there were a whole host of very small words inscribed there, an entire book about Peter Augustus Duchene composed atop his palm.

“Huh,” she said at last. She dropped his hand and squinted up at his face. “But, of course, you are just a boy.”

“I am ten years old,” said Peter. He took the hat from his head and stood as straight and tall as he was able. “And I am training to become a soldier, brave and true. But it does not matter how old I am. You took the florit, so now you must give me my answer.”

“A soldier brave and true?” said the fortuneteller. She laughed and spat on the ground. “Very well, soldier brave and true, if you say it is so, then it is so. Ask me your question.”

Peter felt a small stab of fear. What if, after all this time, he could not bear the truth? What if he did not really want to know?

“Speak,” said the fortuneteller. “Ask.”

“My parents,” said Peter.

“That is your question?” said the fortuneteller. “They are dead.”

Peter’s hands trembled. “That is not my question,” he said. “I know that already. You must tell me something that I do not know. You must tell me of another – you must tell me…”

The fortuneteller narrowed her eyes. “Ah,” she said. “Her? Your sister? That is your question? Very well. She lives.”

Peter’s heart seized upon the words.

She lives. She lives!

“No, please,” said Peter. He closed his eyes. He concentrated. “If she lives, then I must find her; so my question is, how do I make my way there, to where she is?”

He kept his eyes closed; he waited.

“The elephant,” said the fortuneteller.

“What?” Peter said. He opened his eyes, certain that he had misunderstood.

“You must follow the elephant,” said the fortuneteller. “She will lead you there.”

Peter’s heart, which had risen up high inside him, now sank slowly back to its normal resting place. He put his hat on his head. “You are having fun with me,” he said. “There are no elephants here.”

“Just as you say,” said the fortuneteller. “That is surely the truth, at least for now. But perhaps you have not noticed: the truth is forever changing.” She winked at him. “Wait awhile,” she said. “You will see.”

Peter stepped out of the tent. The sky was grey and heavy with clouds, but everywhere people talked and laughed. Vendors shouted and children cried and a beggar with a black dog at his side stood in the centre of it all and sang a song about the darkness.

There was not a single elephant in sight.

Still, Peter’s stubborn heart would not be silenced. It beat out the two simple, impossible words over and over again:

She lives, she lives, she lives

.

Could it be?

No, it could not be, for that would mean that Vilna Lutz had lied to him, and it was not at all an honourable thing for a soldier, a superior officer, to lie. Surely Vilna Lutz would not lie. Surely he would not.

Would he?

“It is winter,” sang the beggar. “It is dark and cold, and things are not what they seem, and the truth is forever changing.”

“I do not know what the truth is,” said Peter, “but I do know that I must confess. I must tell Vilna Lutz what I have done.” He squared his shoulders, adjusted his hat and began the long walk back to the Apartments Polonaise.

As he walked, the winter afternoon turned to dusk and the grey light gave way to gloom, and Peter thought: The fortuneteller is lying; no, Vilna Lutz is lying; no, it is the fortuneteller who lies; no, no, it is Vilna Lutz … on and on like that, the whole way back.

And when he came to the Apartments Polonaise, he climbed the stairs to the attic apartment very slowly, putting one foot carefully in front of the other, thinking with each step, He lies; she lies; he lies; she lies.

The old soldier was waiting for him, sitting in a chair at the window, a single candle lit, the papers of a battle plan in his lap, his shadow cast large on the wall behind him.

“You are late, Private Duchene,” said Vilna Lutz. “And you are empty-handed.”

“Sir,” said Peter. He took off his hat.

“I have no fish and no bread. I gave the money to a fortuneteller.”

“A fortuneteller?” said Vilna Lutz. “A fortuneteller!” He tapped his left foot, the one made of wood, against the floorboards. “A fortuneteller? You must explain yourself.”

Peter said nothing.

Tap, tap, tap

went Vilna Lutz’s wooden foot,

tap, tap, tap

. “I am waiting,” he said. “Private Duchene, I am waiting for you to explain.”

“It is only that I have doubts, sir,” said Peter. “And I know that I should not have doubts—”

“Doubts! Doubts? Explain yourself.”

“Sir, I cannot explain myself. I have been trying the whole way here. There is no explanation that will suffice.”

“Very well, then,” said Vilna Lutz. “You will allow me to explain for you. You have spent money that did not belong to you. You have spent it in a foolish way. You have acted dishonourably. You will be punished. You will retire without your evening rations.”

“Sir, yes, sir,” said Peter, but he continued to stand, his hat in his hands, in front of Vilna Lutz.

“Is there something else you wish to say?”

“No. Yes.”

“Which is it, please? No? Or yes?”

“Sir, have you yourself ever told a lie?” said Peter.

“I?”

“Yes,” said Peter. “You. Sir.”

Vilna Lutz sat up straighter in his chair. He raised a hand and stroked his beard, tracing the line of it, making certain that the hairs were arranged just so, that they came together in a fine, military point. At last he said, “You who spend money that is not yours – you who spend the money of others like a fool –

you

will speak to

me

of who lies?”

“I am sorry, sir,” said Peter.

“I am quite certain that you are,” said Vilna Lutz. “You are also dismissed.” He picked up his papers. He held the battle plan up to the light of the candle and muttered to himself, “So, and it must be so, and then … so.”

Later that night, when the candle was quenched and the room was in darkness and the old soldier was snoring in his bed, Peter Augustus Duchene lay on his pallet on the floor and looked up at the ceiling and thought, He lies; she lies; he lies; she lies.

Someone lies, but I do not know who.

If

she

lies, with her ridiculous talk of elephants, then I am, as Vilna Lutz said, a fool – a fool who believes that an elephant will appear and lead me to a sister who is dead.