The Magician's Elephant (4 page)

Read The Magician's Elephant Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

Every afternoon, the magician and Madam LaVaughn faced each other in the gloom of the prison and said exactly the same thing.

The noblewoman’s manservant was named Hans Ickman, and he had been in the service of Madam LaVaughn since she was a child. He was her adviser and confidant, and she trusted him in all things.

Before he came to serve Madam LaVaughn, however, Hans Ickman had lived in a small town in the mountains, and he had had there a family: brothers, a mother and a father, and a dog who was famous for being able to leap across the river that ran through the woods beyond the town.

The river was too wide for Hans Ickman and his brothers to leap across. It was too wide even for a grown man to leap. But the dog would take a running jump and sail effortlessly across the water. She was a white dog and small, and other than her ability to jump the river, she was in no way extraordinary.

Hans Ickman, as he aged, had forgotten about the dog entirely; her miraculous ability had receded to the back of his mind. But the night that the elephant had come crashing through the ceiling of the opera house, the manservant had remembered again, for the first time in a long while, the little white dog.

Standing in the prison, listening to the endless and unvarying exchange between Madam LaVaughn and the magician, Hans Ickman thought about being a boy, waiting on the bank of the river with his brothers, and watching the dog run and then fling herself into the air. He remembered how, in mid-leap, she would always twist her body, a small unnecessary gesture, a fillip of joy, to show that this impossible thing was easy for her.

Madam LaVaughn said, “But perhaps you do not understand.”

The magician said, “I intended only lilies.”

Hans Ickman closed his eyes and remembered the dog suspended in the air above the river, her white body set afire by the light of the sun.

But what was the dog’s name? He could not recall. She was gone and her name was gone with her. Life was so short; so many beautiful things slipped away. Where, for instance, were his brothers now? He did not know; he could not say.

Madam LaVaughn said, “I was crushed, crushed by an elephant!”

The magician said, “I intended only—”

“Please,” said Hans Ickman. He opened his eyes. “It is important that you say what you mean to say. Time is too short. You must speak words that matter.”

The magician and the noblewoman were silent for a moment.

And then Madam LaVaughn opened her mouth. She said, “But perhaps you do not understand.”

The magician said, “I intended only lilies.” “Enough,” said Hans Ickman. He took hold of Madam LaVaughn’s chair and turned it around. “That is enough. I cannot bear to hear it any more. I truly cannot.”

He wheeled her away, down the long corridor and out of the prison and into the cold, dark Baltesian afternoon.

“But perhaps you do not understand. I was crippled—”

“No,” said Hans Ickman, “no.”

Madam LaVaughn fell silent.

And it was in this manner that she paid her last official visit to the magician in prison.

Peter could, from the window of the attic room in the Apartments Polonaise, see the turrets of the prison. He could see, too, the spire of the city’s largest cathedral and the gargoyles crouched there, glowering, on its ledges. If he looked out into the distance, he could see the great, grand homes of the nobility high atop the hill. Below him were the twisting, turning cobblestoned streets, the small shops with their crooked tiled roofs, and the pigeons who forever perched atop them, singing sad songs that did not quite begin and never truly ended.

It was a terrible thing to gaze upon it all and know that somewhere, beneath one of those roofs, hidden, perhaps, in some dark alley, was the very thing that he needed, wanted, and could not have.

How could it be that against all odds, all expectations, all reason, an elephant could miraculously appear in the city of Baltese and then just as quickly disappear; and that he, Peter Augustus Duchene, who needed desperately to find her, did not know – could not even begin to imagine – the how or where of searching for her?

Looking out over the city, Peter decided that it was a terrible and complicated thing to hope, and that it might be easier, instead, to despair.

“Come away from the window,” Vilna Lutz called to Peter.

Peter held very still. He found that it was hard now for him to look at Vilna Lutz’s face.

“Private Duchene,” said Vilna Lutz.

“Sir?” said Peter without turning.

“A battle is being waged,” said Vilna Lutz, “a battle between good and evil! Whose side will you do battle on? Private Duchene!”

Peter turned and faced the old man.

“What is this? Are you crying?”

“No,” said Peter. “I am not.” But when he put a hand to his face, he was surprised to discover that his cheek was wet.

“That is good,” said Vilna Lutz. “Soldiers do not weep; at least, they should not weep. It is not to be borne, the weeping of soldiers. Something is amiss in the universe when a soldier cries. Hark! Do you hear the rattle of muskets?”

“I do not,” said Peter.

“Oh, it is cold,” said the old soldier. “Still, we must practise manoeuvres. The marching must begin. Yes, the marching must begin.”

Peter did not move.

“Private Duchene! You will march! Armies must move. Soldiers must march.”

Peter sighed. His heart was so heavy inside him that he did not, in truth, think that he had it in him to move at all. He lifted one foot and then the other.

“Higher,” said Vilna Lutz. “March with purpose; march like a man. March as your father would have marched.”

What difference does it make if an elephant has come? Peter thought as he stood in the same place and marched without going anywhere at all. It is just some grand and terrible joke that the fortuneteller has told me. My sister is not alive. There is no reason to hope.

The longer he marched, the more convinced Peter became that things were indeed hopeless and that an elephant was a ridiculous answer to any question – but a particularly ridiculous answer to a question posed by the human heart.

T

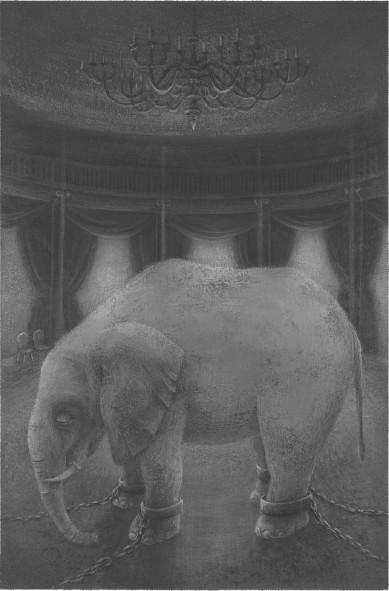

he people of the city of Baltese became obsessed with the elephant.

In the market square and in the ballrooms, in the stables and in the gaming houses, in the churches and in the squares, it was “the elephant,” “the elephant that came through the roof,” “the elephant conjured by the magician,” “the elephant that crippled the noblewoman”.

The bakers of the city concocted a flat, oversized pastry and filled it with cream and sprinkled it with cinnamon and sugar and called the confection an elephant ear, and the people could not get enough of it.

The street vendors sold, for exorbitant prices, chunks of plaster that had fallen onto the stage when the elephant made her dramatic appearance. “Cataclysm!” the vendors shouted. “Mayhem! Possess the plaster of disaster!”

The puppet shows in the public gardens featured elephants that came crashing onto the stage, crushing the other puppets beneath them, making the young children laugh and clap in delight and recognition.

From the pulpits of the churches the preachers spoke about divine intervention, the surprises of fate, the wages of sin, and the dire consequences of magic gone afoul.

The elephant’s dramatic and unexpected appearance changed the way the people of the city of Baltese spoke. If, for instance, a person was deeply surprised or moved, he or she would say, “I was, you understand, in the presence of the elephant.”

As for the fortunetellers of the city, they were kept particularly busy. They gazed into their teacups and crystal balls. They read the palms of thousands of hands. They studied their cards and cleared their throats and predicted that amazing things were yet to come. If elephants could arrive without warning, then a dramatic shift had certainly occurred in the universe. The stars were aligning themselves for something even more spectacular; rest assured, rest assured.

Meanwhile, in the dance halls and in the ballrooms, the men and the women of the city, the low and the high, danced the same dance: a swaying, lumbering two-step called, of course, the Elephant.

Everywhere, always, it was “the elephant, the elephant, the magician’s elephant”.

* * *

“It is absolutely ruining the social season,” said the Countess Quintet to her husband. “It is all people will speak of. Why, it is as bad as a war. Actually, it is worse. At least with a war, there are well-dressed heroes capable of making interesting conversation. But what do we have here? Nothing, nothing but a smelly, loathsome beast, and yet people

will

insist on speaking of nothing else. I truly feel, I am quite certain, I am absolutely convinced, that I will lose my mind if I hear the word

elephant

one more time.

“Elephant,” muttered the count.

“What did you say?” said the countess. She whirled around and stared at her husband.

“Nothing,” said the count.

“Something must be done,” said the countess.

“Indeed,” said Count Quintet, “and who will do it?”

“I beg your pardon?”

The count cleared his throat. “I only wanted to say, my dear, that you must admit that what occurred was indeed truly extraordinary.”

“Why must I admit it? What was extraordinary about it?”

The countess had not been present at the opera house that fateful evening, and so she had missed the cataclysmic event; and the countess was the kind of person who hated, most horribly, to miss cataclysmic events.

“Well, you see—” began Count Quintet.

“I do not see,” said the countess. “And you will not make me see.”

“Yes,” said her husband, “I suppose that much is true.”

Unlike his wife, the count had been in attendance at the opera house that night. He had been seated so close to the stage that he had felt the rush of displaced air that presaged the elephant’s appearance.

“There must be a way to wrest control of the situation,” said the Countess Quintet. She paced back and forth. “There must be some way to regain the social season.”

The count closed his eyes. He felt again the breeze of the elephant’s arrival. The whole thing had happened in an instant, but it had also occurred so slowly. He, who never cried, had cried that night, because it was as if the elephant had spoken to him and said, “Things are not at all what they seem to be; oh no, not at all.”

To be in the presence of such a thing, to feel such a feeling!

Count Quintet opened his eyes.

“My dear,” he said, “I have the solution.”

“You do?” said the countess.

“Yes.”

“And what, exactly, would the solution be?”

“If everyone speaks of nothing but the elephant, and if you desire to be the centre, the heart, of the social season, then you must be the one with the thing that everyone speaks of.”

“But what can you mean?” said the countess. Her lower lip quivered. “Whatever can you mean?”

“What I mean, my dear, is that you must bring the magician’s elephant here.”

When the countess demanded of the universe that it move in a certain way, the universe, trembling and eager to please, did as she bade it do.

And so, in the matter of the elephant and the countess, this is how it happened – this is how it unfolded. There was not, at her home, as lavish and well appointed a home as it was, a door large enough for an elephant to walk through. The Countess Quintet hired a dozen craftsmen. The men worked around the clock, and within a day a wall had been knocked down and an enormous, brightly painted, handsomely decorated door installed.

The elephant was summoned and arrived under cover of night, escorted by the chief of police, who ushered her through the door that had been constructed expressly for her; then, relieved beyond all measure to have done with the affair, he tipped his hat to the countess and left.

The door was closed and locked behind him, and the elephant became the property of the Countess Quintet, who had paid the owner of the opera house money sufficient to repair and retile the whole of his roof a dozen times over.

The elephant belonged entirely to the Countess Quintet, who had written to Madam LaVaughn and expressed at great length and with the utmost eloquence her sorrow over the unspeakable and inexplicable tragedy that had befallen the noblewoman; she offered Madam LaVaughn her full and enthusiastic support in the further prosecution and punishment of the magician.