The Magician's Elephant (9 page)

Read The Magician's Elephant Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

And then Peter was struck by a thought so wondrous that he stopped walking. He put his hat on his head. He took it off. He put it back on again. He took it off.

The magician

.

If the world held magic powerful enough to make the elephant appear, then there had to exist, too, magic in equal measure, magic powerful enough to undo what had been done.

There had to be magic that could send the elephant home.

“The magician,” said Peter out loud, and then he said, “Leo Matienne!”

He put his hat on his head. He began to run.

L

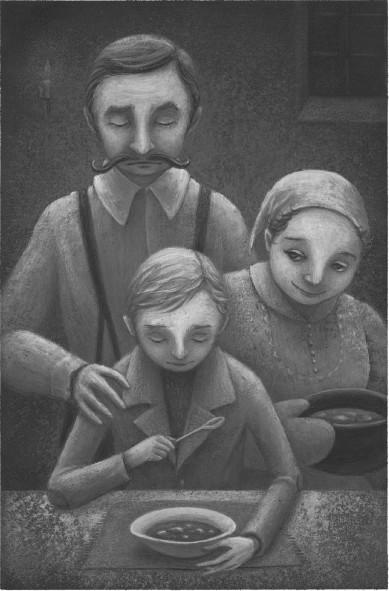

eo Matienne opened the door of his apartment. He was barefoot. A napkin was tied around his neck, and a bit of carrot and a crumb of bread were caught in his moustache. The smell of mutton stew wafted out into the cold, dark street.

“It is Peter Augustus Duchene!” said Leo Matienne. “And he has his hat on his head. And he is here, on the ground, instead of up there, acting like a cuckoo in a clock.”

“I am very sorry to disturb you at your dinner,” said Peter, “but I must see the magician.”

“You must do what?”

“I need you to take me to the prison so that I may see the magician. You are a policeman, an officer of the law; surely they will let you inside.”

“Who is it?” called Gloria Matienne. She came to the door and stood beside her husband.

“Good evening, Madam Matienne,” said Peter. He took off his hat and bowed to Gloria.

“And a good evening to you,” said Gloria.

“Yes, good evening,” said Peter. He put his hat back on his head. “I am sorry to disturb you at your dinner, but I need to go to the prison immediately.”

“He needs to go to the prison?” said Gloria Matienne to her husband. “Is that what he said? Have mercy! What kind of request is that for a child to make? And look at him, please. He is so skinny that you can see right through him. He is … what is the word?”

“Transparent?” said Leo.

“Yes,” said Gloria, “exactly that. Transparent. Does that old man not feed you? In addition to no love, is there no food in that attic room?”

“There is bread,” said Peter. “And also fish, but they are very small fish, exceedingly small.”

“You must come inside,” said Gloria. “That is the thing which you must immediately do. You must come inside.”

“But—” said Peter.

“Come inside,” said Leo. “We will talk.”

“Come inside,” said Gloria Matienne. “First we will eat, and

then

we will talk.”

There was, in the apartment of Leo and Gloria Matienne, a wonderful fire blazing, and the kitchen table was pulled up close to the hearth.

“Sit,” said Leo.

Peter sat. His legs were shaking and his heart was beating fast, as if he were still running. “I do not think that there is much time,” he said. “I do not think that there is enough time, truly, to dine.”

Gloria put a bowl of stew in Peter’s hands. “Eat,” she said.

Peter raised the spoon to his lips. He chewed. He swallowed.

It had been a long time since he had eaten anything besides tiny fish and old bread.

And so when Peter had his first bite of stew, it overwhelmed him. The warmth of it, the richness of it, knocked him backwards; it was as if a gentle hand had pushed him when he was not expecting it. Everything he had lost came flooding back: the garden, his father, his mother, his sister, the promises that he had made and could not keep.

“What’s this?” said Gloria Matienne. “The boy is crying.”

“Shh,” said Leo. He put his hand on Peter’s shoulder. “Shh. Don’t worry, Peter. Everything will be good. All will be well. We will do together whatever it is that needs to be done. But for now, you must eat.”

Peter nodded. He raised his spoon. Again he chewed and swallowed, and again he was overcome. He could not help it. He could not stop the tears; they flowed down his cheeks and into the bowl. “It is very good stew, Madam Matienne,” he managed to say. “Truly, it is excellent stew.”

His hands shook; the spoon rattled against the bowl.

“Here, now,” said Gloria Matienne, “don’t spill it.”

It is gone, thought Peter. All of it is gone! And there is no way to get it back.

“Eat,” said Leo Matienne again, very gently.

Peter looked the truth of what he had lost full in the face.

And then he ate.

When Peter was done, Leo Matienne sat down in the chair beside him and said, “Now you must tell us everything.”

“Everything?” said Peter.

“Yes, everything,” said Leo Matienne. He leaned back in his chair. “Begin at the beginning.”

Peter started in the garden. He began his story with his father throwing him up high in the air and catching him. He began with his mother dressed all in white, laughing, her stomach round like a balloon.

“The sky was purple,” said Peter. “The lamps were lit.”

“Yes,” said Leo Matienne. “I can see it all very well. And where is your father now?”

“He was a soldier,” said Peter, “and he died on the battlefield. Vilna Lutz served with him and fought beside him. He was his friend. He came to our house to deliver the news of my father’s death.”

“Vilna Lutz,” said Gloria Matienne, and it was as if she were uttering a curse.

“When my mother heard the news, the baby started to come: my sister, Adele.” Peter stopped. He took a deep breath. “My sister was born, and my mother died. Before she died, I promised her that I would always watch out for the baby. But then I could not, because the midwife took the baby away and Vilna Lutz took me with him, to teach me how to be a soldier.”

Gloria Matienne stood. “Vilna Lutz!” she shouted. She shook a fist at the ceiling. “I will have a word with him.”

“Sit, please,” said Leo Matienne.

Gloria sat.

“And what became of your sister?” said Leo to Peter.

“Vilna Lutz told me that she died. He said that she was born dead, stillborn.”

Gloria Matienne gasped.

“He said that. But he lied. He lied. He has admitted that he lied. She is not dead.”

“Vilna Lutz!” said Gloria Matienne. Again she leaped to her feet and shook her fist at the ceiling.

“First the fortuneteller told me that she lives, and then my own dream told me the same. And the fortuneteller told me also that the elephant –

an

elephant – would lead me to her. But today, this afternoon, I saw the elephant, Leo Matienne, and I know that she will die if she cannot go home. She must go home. The magician must return her there.”

Leo crossed his arms and tipped his chair back on two legs.

“Don’t do that,” said Gloria. She sat down again. “It is very bad for the chair.”

Leo Matienne came slowly forward until all four chair legs were again resting on the floor. He smiled. “What if?” he said.

“Oh, don’t start,” said his wife. “Please, don’t start.”

“Why not?”

From somewhere high above them, there came a muffled

thump

, the sound of Vilna Lutz beating his wooden foot on the floor, demanding something.

“Could it be?” said Leo.

“Yes,” said Peter. He did not look up at the ceiling. He kept his eyes on Leo Matienne. “What if?” he said to the policeman.

“Why not?” said Leo back to him. He smiled.

“Enough,” said Gloria.

“No,” said Leo Matienne, “not enough. Never enough. We must ask ourselves these questions as often as we dare. How will the world change if we do not question it?”

“The world cannot be changed,” said Gloria. “The world is what the world is and has for ever been.”

“No,” said Leo Matienne softly, “I will not believe that. For here is Peter standing before us, asking us to make it something different.”

Thump, thump, thump

went Vilna Lutz’s foot above them.

Gloria looked up at the ceiling. She looked over at Peter.

She shook her head. She nodded her head. And then, slowly, she nodded it again.

“Yes,” said Leo Matienne, “yes, that is what I thought too.” He stood and took the napkin from his neck. “It is time for us to go to the prison.”

He put his arms around his wife and pulled her close. She rested her cheek against his for a moment, and then she pulled away from Leo and turned to Peter.

“You,” she said.

“Yes,” said Peter. He stood straight before her, like a soldier awaiting inspection, and so he was not prepared at all when she grabbed him and pulled him close, enveloping him in the smell of mutton stew and starch and green grass.

Oh, to be held!

He had forgotten entirely what it meant. He wrapped his arms around Gloria Matienne and began, again, to cry.

“There,” she said. She rocked him back and forth. “There, you foolish, beautiful boy who wants to change the world. There, there. And who could keep from loving you? Who could keep from loving a boy so brave and true?”

I

n the house of the countess, in the dark and empty ballroom, the elephant slept. She dreamed she was walking across a wide savannah. The sky above her was a brilliant blue. She could feel the warmth of the sun on her back. In her dream the boy appeared a long way ahead of her and stood waiting.

When she at last drew close to him, he looked at her as he had done that afternoon. But he said nothing. He simply fell into step beside her.

They walked together through the tall grass, and the elephant, in her dream, thought that this was a wonderful thing, to walk beside the boy. She felt that things were exactly as they should be, and she was happy.

The sun was so warm!

In the prison the magician lay upon his cloak, staring up at the window, hoping for the clouds to break and the bright star to appear.

He could no longer sleep.

Every time he closed his eyes, he saw the elephant crashing through the ceiling of the opera house and landing on top of Madam LaVaughn. The image bedevilled him to the point where he could get no rest, no respite. All he could think of was the elephant and the amazing, stupendous magic he had performed to call her forth.

At the same time, he was achingly, devastatingly lonely, and he wished, with the whole of his heart, to see a face, any human face. He would have been delighted, pleased beyond measure, to gaze upon even the accusatory, pleading countenance of the crippled Madam LaVaughn. If she appeared beside him right now, he would show her the star that was sometimes visible through his window. He would say to her, “Have you, in truth, ever seen something so heartbreakingly lovely? What are we to make of a world where stars shine bright in the midst of so much darkness and gloom?”

All of which is to say that the magician was awake that night when the outer door of the prison clanged open and two sets of footsteps sounded down the long corridor.

He stood.

He put on his cloak.

He looked out through the bars of his cell and saw the light of a lantern shining in the darkened corridor. His heart leaped inside him. He called out to the approaching light.

And what did the magician say?

You know full well the words he spoke.

“I intended only lilies!” shouted the magician. “Please, I intended only a bouquet of lilies.”

In the light from the lantern that Leo Matienne held aloft, Peter could see the magician all too clearly. His beard was long and wild, his fingernails ragged and torn, his cloak covered in a patina of mould. His eyes burned bright, but they were the eyes of a cornered animal: desperate and pleading and angry all at once.