The Magician's Elephant (7 page)

Read The Magician's Elephant Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

“Yes, sir,” said Peter, “I admire it.”

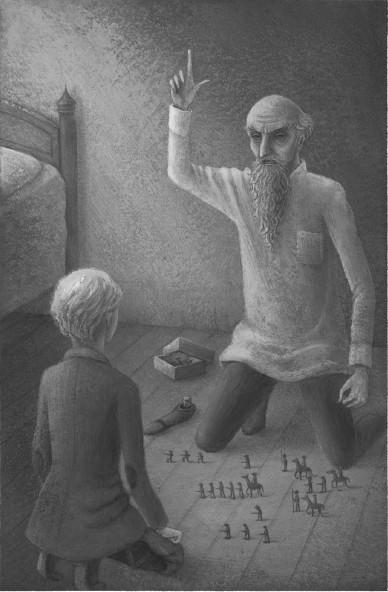

“You must, then, give me your undivided attention,” said Vilna Lutz. He picked up his wooden foot and beat it against the floor. “This is important. This is the work of your father I am speaking of. This is a man’s work.”

Peter looked down at the toy soldiers and thought about his father in a field full of mud, a bayonet wound in his side. He thought about his father bleeding. He thought about him dying.

And then he remembered the dream of Adele, the weight of her in his arms and the golden light that had been outside the door. He remembered his father holding him, catching him, in the garden.

And for the first time, soldiering did not, in any way, seem like a man’s work to Peter. Instead it seemed like foolishness – a horrible, terrible, nightmarish foolishness.

“So,” said Vilna Lutz. He cleared his throat. “As I was saying, as I was illuminating, as I was elucidating, yes, these men, these brave, brave soldiers, under the direct orders of the brilliant General Von Flickenhamenger, came around from behind. They outflanked the enemy. And that, ultimately, is how the battle was won. Does that make sense?”

Peter looked down at the soldiers arranged carefully and just so. He looked up at Vilna Lutz’s face and then down again at the soldiers.

“No,” he said at last.

“No?”

“No. It does not make sense.”

“Well, then, tell me what you see when you look upon it, if you do not see the sense of it.”

“I look upon it and wish that it could be undone.”

“Undone?” said Vilna Lutz.

“Yes. Undone. No wars. No soldiers.”

Vilna Lutz stared at Peter with his mouth agape and the point of his beard trembling.

Peter, looking back at him, felt something unbearably hot rise up in his throat; he knew that now the words would finally come.

“She lives,” he said. “That is what the fortuneteller told me. She lives, and an elephant will lead me to her. And because an elephant has come out of nowhere, out of nothing, I believe her. Not you. I do not – I cannot – any longer believe you.”

“What is this you are talking about? Who lives?”

“My sister,” said Peter.

“Your sister? Am I mistaken? Were we speaking of the domestic sphere? No. We were not. We were speaking of battles, you and I. We were speaking of the brilliance of generals and the bravery of foot soldiers.” Vilna Lutz beat his wooden foot against the floorboards. “Battles and bravery and strategy, that is what we were speaking of.”

“Where is she? What happened to her?” The old soldier grimaced. He put down the foot and pointed his index finger heavenwards. “I told you. I have told you many times. She is with your mama, in heaven.”

“I heard her cry,” said Peter. “I held her.”

“Bah,” said Vilna Lutz. His finger, still pointing heavenwards, trembled. “She did not cry. She could not cry. Stillborn. She was stillborn. The breath never reached her lungs. She never drew breath.”

“She cried. I remember. I know it to be true.”

“And what of it? What if she did cry? That she cried does not mean that she lived – not at all, not at all. If every babe who cried were still alive, well, then, the world would be a very crowded place indeed.”

“Where is she?” said Peter.

Vilna Lutz let out a small sob.

“Where?” said Peter again.

“I do not know,” said the old soldier. “The midwife took her away. She said that she was too small, that she could not possibly put something so delicate into the hands of one such as me.”

“You said she died. Time and again, you told me that she was dead. You lied.”

“Do not call it a lie. Call it scientific conjecture. Babes without their mothers often will not live. And she was so small.”

“You lied to me.”

“No, no, Private Duchene. I lied

for

you, to protect you. What could you have done if you had known? It would only have hurt your heart to know. I cared for you – you, who would and could become a soldier like your father, a man I admired. I did not take your sister, because the midwife would not let me; she was so small, so impossibly small. What do I know of infants and their needs? I know of soldiering, not mothering.”

Peter got up from the floor. He walked to the window and stood looking out at the cathedral spire, the birds wheeling in the air.

“I am done talking now, sir,” said Peter. “Tomorrow I will go to the elephant and then I will find my sister and I will be done with you. I am done, too, with being a soldier, because soldiering is a useless and pointless thing.”

“Do not say something so terrible,” said Vilna Lutz. “Think of your father.”

“I am thinking of my father,” said Peter.

And he was.

He was thinking of his father in the garden.

And he was thinking of him on the battlefield, bleeding to death.

T

he weather worsened.

Although it did not seem possible, it became colder.

Although it did not seem possible, it grew darker.

It would not snow.

And in the cold, dark dorm room at the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, Adele continued to dream of the elephant. The dream was so persistent that Adele could, after a time, repeat verbatim the words that the elephant spoke to Sister Marie when she came to the door. There was, in particular, one sentence that the elephant spoke that was so full of beauty and promise that Adele took to saying it to herself during the day: “‘It is the one you are calling Adele I am coming for to keep.’” She said these words over and over, as if they were a poem or a blessing or a prayer. “‘It is the one you are calling Adele I am coming for to keep; it is the one you are calling Adele I am coming for to keep—’”

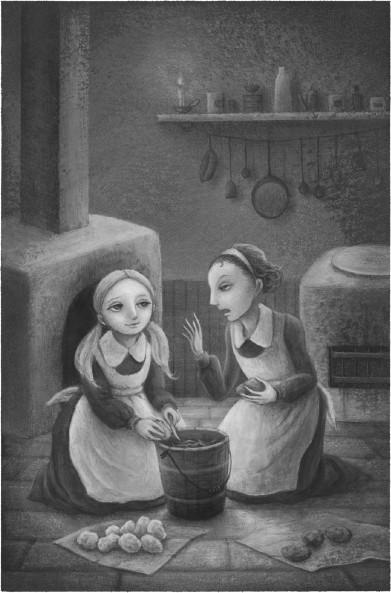

“Who are you talking to?” said an older girl named Lisette.

She and Adele were in the orphanage kitchen together, bent over a bucket, peeling potatoes.

“No one,” said Adele.

“But your lips were moving,” said Lisette. “I saw them move. You were saying something.”

“I was saying the elephant’s words,” said Adele.

“The elephant’s words?”

“The elephant from my dreams. She speaks to me.”

“Oh, of course, silly me, the speaking elephant from your dreams,” said Lisette. She snorted.

“The elephant knocks at the door and asks for me,” said Adele. She lowered her voice. “I believe that she has come to take me away from here.”

“To take you away?” said Lisette. Her eyes narrowed. “And where would she take you?”

“Home,” said Adele.

“Ha! Listen to her!” said Lisette. “Home.” She snorted again. “How old are you?”

“Six,” said Adele. “Almost seven.”

“Yes, well, you are very exceptionally, amazingly stupid for almost seven years old,” said Lisette.

There came a knock at the kitchen door.

“Hark!” said Lisette. “Someone knocks! May be it is an elephant.” She got up and went to the door and threw it wide. “Look, Adele,” she said, turning back with a terrible smile on her face. “Look who is here. It is an elephant come to take you home.”

There was not, of course, an elephant at the door. Instead, there stood the neighbourhood beggar and his dog.

“We have nothing to give you,” said Lisette in a loud voice. “We’re orphans. This is an orphanage.” She stamped her foot.

“We have nothing to give,” sang the beggar, “but look, Adele, an elephant, and this is wonderful news.”

Adele looked at the beggar’s face and saw that he was truly, terribly hungry.

“Look, Adele, an elephant,” he sang, “but you must know that the truth is always changing.”

“Don’t sing,” said Lisette. She slammed the door shut and came and sat down next to Adele. “You see, now, who comes and knocks at the door here? Blind dogs. And beggars who sing meaningless songs. Do you think they have come to take us home?”

“He was hungry,” said Adele. She felt an unsolicited tear roll down her cheek. It was followed by another and then another.

“So what?” said Lisette. “Who do you know who isn’t hungry?”

“No one,” answered Adele truthfully. She herself was always hungry.

“Yes,” said Lisette, “we are all hungry. So what?”

Adele could think of nothing to say in reply.

All she had were the words of a dream elephant. They were not much, but they were hers, and she began again to say them to herself: “‘It is the one you are calling Adele I am coming for to keep; it is the one you are calling Adele I am coming for to keep; it is the one you are calling Adele—’”

“Quit moving your lips,” said Lisette.

“Can’t you see that no one intends to come for us?”

O

n the first Saturday of the month, the city of Baltese turned out to see the elephant. The line snaked from the home of the Countess Quintet out into the street and down the hill as far as the eye could see. There were young men with waxed moustaches and pomaded hair, and old ladies dressed in borrowed finery, their wrinkled faces scrubbed clean. There were candle makers who smelled of warm beeswax, washerwomen with roughened hands and hopeful faces, babies still at their mothers’ breasts, and old men who leaned heavily on canes.

Milliners stood with their heads held high, their latest creations displayed proudly on their heads. Lamplighters, their eyes heavy from lack of sleep, stood next to street sweepers, who held their brooms before them as if they were swords. Priests and fortunetellers stood side by side and eyed each other with distaste and wariness.

Everyone, it seemed, was there: the whole city of Baltese stood in line to see the elephant.

And everyone, each person, had hopes and dreams, wishes for revenge, and desires for love.

They stood together.

They waited.

And secretly, deep within their hearts, even though they knew it could not truly be so, they each expected that the mere sight of the elephant would somehow deliver them, would make their wishes and hopes and desires come true.

Peter stood in line directly behind a man who was dressed entirely in black and who had atop his head a black hat with an exceptionally wide brim. The man rocked from heel to toe, muttering, “The dimensions of an elephant are most impressive. The dimensions of an elephant are impressive in the extreme. I will now detail for you the dimensions of an elephant.”