The Magician's Elephant (10 page)

Read The Magician's Elephant Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

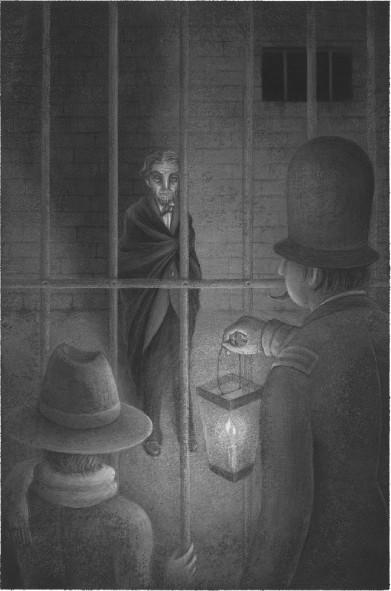

Peter’s heart sank. This man did not look as if he could perform any magic at all, much less the huge magic, the tremendous magic, of sending an elephant home.

“Who are you?” said the magician. “Who has sent you?”

“My name is Leo Matienne,” said Leo, “and this is Peter Augustus Duchene, and we have come to speak to you about the elephant.”

“Of course, of course,” said the magician. “What else would you speak to me of but the elephant?”

“We want you to do the magic that will send her home,” said Peter.

The magician laughed; it was not a pleasant sound. “Send her home, you say? And why would I do that?”

“Because she will die if you do not,” said Peter.

“And why will she die?”

“She is homesick,” said Peter. “I think that her heart is broken.”

“A homesick, broken-hearted magic trick,” said the magician. He laughed again. He shook his head. “It was all so magnificent when it happened; it was all so wondrous when it occurred – you would not believe it; truly you would not. And look what it has come to.”

Somewhere in the prison, someone was crying. It was the kind of strangled weeping that Vilna Lutz sometimes gave himself over to when he thought that Peter was asleep.

The world is broken, thought Peter, and it cannot be fixed.

The magician kept still, his head pressed against the bars. The sound of the prisoner weeping rose and fell, rose and fell. And then Peter saw that the magician was crying too; great, lonely tears rolled down his face and disappeared into his beard.

May be it was not too late after all.

“I believe,” said Peter very quietly.

“What do you believe?” said the magician without moving.

“I believe that things can still be set right. I believe that you can perform the necessary magic.”

The magician shook his head. “No.” He said the word quietly, as if he were speaking it to himself. “No.”

There was a long silence.

Leo Matienne cleared his throat, once, and then again. He opened his mouth and spoke two simple words. He said, “What if?”

The magician raised his head then and looked at the policeman. “What if?” he said. “‘What if?’ is a question that belongs to magic.”

“Yes,” said Leo, “to magic and also to the world in which we live every day. So: what if? What if you merely tried?”

“I tried already,” said the magician. “I tried and failed to send her back.” The tears continued to roll down his face. “You must understand: I did not want to send her back; she was the finest magic I have ever performed.”

“To return her to where she belongs would be a fine magic too,” said Leo Matienne.

“So you say,” said the magician. He looked at Leo Matienne and then at Peter and then back again at Leo Matienne.

“Please,” said Peter.

The light from the lantern in Leo’s outstretched arm flickered, and the magician’s shadow, cast on the wall behind him, reared back suddenly and then grew larger. The shadow stood apart from him as if it were another creature entirely, watching over him, waiting anxiously, along with Peter, for the magician to decide what seemed to be the fate of the entire universe.

“Very well,” said the magician at last. “I will try. But I will need two things. I will need the elephant, for I cannot make her disappear without her being present. And I will need Madam LaVaughn. You must bring both the elephant and the noblewoman here to me.”

“But that is impossible,” said Peter.

“Magic is always impossible,” said the magician. “It begins with the impossible and ends with the impossible and is impossible in between. That is why it is magic.”

M

adam LaVaughn was often kept awake at night by shooting pains in her legs. And because she was awake, she insisted that the whole household stay awake with her.

Further, she insisted that they listen again to the story of how she had dressed for the theatre that night, how she had walked into the building (Walked! On her own two legs!) entirely and absolutely innocent of the fate that awaited her inside. She insisted that the gardener and the cook, the serving maids and the chambermaids, pretend to be interested as she spoke again of how the magician had selected her from among the sea of hopefuls.

“‘Who, then, will come before me and receive my magic?’ Those were his exact words,” said Madam LaVaughn.

The assembled servants listened (or pretended to) as the noblewoman spoke of the elephant falling from nowhere, of how one minute the notion of an elephant was inconceivable and the next the elephant was an irrefutable fact in her lap.

“Crippled,” said Madam LaVaughn in conclusion, “crippled by an elephant that came through the roof!”

The servants knew these last words so well, so intimately, that they mouthed them along with her, whispering the phrases together as if they were participating in some odd and arcane religious ceremony.

This, then, is what was taking place in the house of Madam LaVaughn that evening when there came a knock at the door, and the butler appeared beside Hans Ickman to announce that there was a policeman waiting outside and that this policeman absolutely insisted on speaking to Madam LaVaughn.

“At this hour?” said Hans Ickman.

But he followed the butler to the door, and there, indeed, stood a policeman, a short man with a ridiculously large moustache.

The policeman stepped forward and bowed and said, “Good evening. I am Leo Matienne. I serve with Her Majesty’s police force. I am not, however, here on official business. I have come instead with a most unusual personal request for Madam LaVaughn.”

“Madam LaVaughn cannot be disturbed,” said Hans Ickman. “The hour is late, and she is in pain.”

“Please,” said a small voice.

Hans Ickman saw then that there was a boy standing behind the policeman and that he held a soldier’s hat in his hand.

“It is important,” said the boy.

The manservant looked into the boy’s eyes and saw himself, young again and still capable of believing in miracles, standing on the bank of the river with his brothers, the white dog suspended in mid-air.

“Please,” said the boy.

And suddenly it came to Hans Ickman, the name of the little white dog. Rose. She was called Rose. And remembering was like fitting a piece of a puzzle into place. He felt a wonderful certainty. The impossible, he thought, the impossible is about to happen again.

He looked past the policeman and the boy and into the darkness beyond them. He saw something swirl through the air. A snowflake. And then another. And another.

“Come in,” said Hans Ickman. He swung the door wide. “You must come inside now. The snow has begun.”

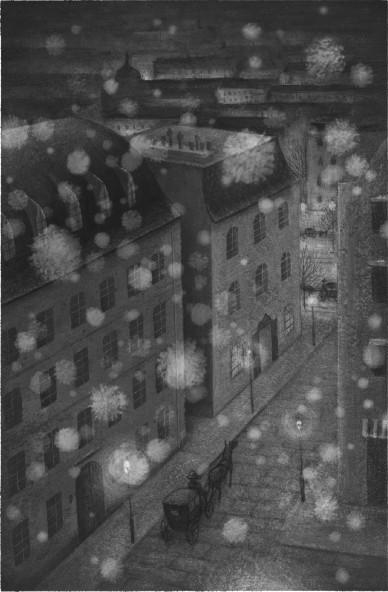

It had indeed begun to snow. It was snowing over the whole of the city of Baltese.

The snow fell in the darkened alleys and on the newly repaired tiles of the opera house. It settled atop the turrets of the prison and on the roof of the Apartments Polonaise. At the home of the Countess Quintet the snow worked to outline the graceful curve of the handle on the elephant door; and at the cathedral it formed fanciful and slightly ridiculous caps for the heads of the gargoyles, who crouched together, gazing down at the city in disgust and envy.

The snow danced around the circles of light that pulsed from the lamps lining the wide boulevards of the city of Baltese. The snow fell in a curtain of white all around the bleak and unprepossessing building that was the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, as if it were working very hard to hide the place from view.

The snow, at last, fell.

And as it snowed, Bartok Whynn dreamed.

He dreamed of carving. He dreamed of doing the work he knew and loved: coaxing figures from stone. Only, in his dream, he did not carve gargoyles, but humans. One was a boy wearing a hat; another, a man with a moustache; and another, a woman sitting, with a man standing to attention behind her.

And each time a new person appeared beneath his hand, Bartok Whynn was astonished and deeply moved.

“You,” he said as he worked, “and you and you. And you.”

He smiled.

And because it was a dream, the people he had fashioned from stone smiled back at him.

As the snow fell, Sister Marie, who sat by the door at the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, dreamed too.

She dreamed that she was flying high over the world, her habit spread out on either side of her like dark wings.

She was terribly pleased, because she had always, secretly, deep within her heart, believed that she could fly. And now here she was, doing what she had long suspected she could do, and she could not deny that it was gratifying in the extreme.

Sister Marie looked down at the world below her and saw millions and millions of stars and thought, I am not flying over the earth at all. Why, I am flying higher than that. I am flying over the very tops of the stars. I am looking down at the sky.

And then she realized that no, no, it

was

the earth that she was flying over, and that she was looking not at the stars but at the creatures of the world, and that they were all, they were each – beggars, dogs, orphans, kings, elephants, soldiers – emitting pulses of light.

The whole of creation glowed.

Sister Marie’s heart grew large in her chest, and her heart, expanding in such a way, allowed her to fly higher and then higher still – but no matter how high she flew, she never lost sight of the glowing earth below her.

“Oh,” said Sister Marie out loud in her sleep, in her chair by the door, “how wonderful. Didn’t I know it? I did. I did. I knew it all along.”

H

ans Ickman pushed Madam LaVaughn’s wheelchair, and Leo Matienne had hold of Peter’s hand. The four of them moved quickly through the snowy streets. They were heading to the home of the countess.

“I do not understand,” said Madam LaVaughn. “I find this all highly irregular.”

“I believe the time has come,” said Hans Ickman.

“The time? The time? The time for what?” said Madam LaVaughn. “Do not speak to me in riddles.”

“The time for you to return to the prison.”

“But it is the middle of the night, and the prison is that way,” said Madam LaVaughn, flinging a heavily bejewelled hand behind her. “The prison is in entirely the opposite direction.”