The Magician's Elephant (5 page)

Read The Magician's Elephant Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

The fate of the elephant rested absolutely in the hands of the Countess Quintet, who had made a very generous contribution indeed to the policemen’s fund.

The elephant, you will now understand, belonged lock, stock and barrel to the countess.

The beast was installed in the ballroom, and the ladies and gentlemen, dukes and duchesses, princes and princesses, and counts and countesses flocked to her.

They gathered around her.

The elephant became, quite literally, the centre of the social season.

P

eter dreamed.

Vilna Lutz was ahead of him in a field, and he, Peter, was running to catch up.

“Hurry!” shouted Vilna Lutz. “You must run like a soldier.”

The field was a field of wheat, and as Peter ran, the wheat grew taller and taller, and soon it was so tall that Vilna Lutz disappeared entirely from view and Peter could only hear his voice shouting, “Hurry, hurry! Run like a man; run like a soldier!”

“It is no good,” said Peter. “No good at all. I have lost him. I will never catch him, and it is pointless to run.”

He sat down and looked up at the blue sky. Around him the wheat continued to grow, forming a golden wall, sealing him in, protecting him. It is almost like being buried, he thought. I will stay here for ever, for all time. No one will ever find me.

“Yes,” he said, “I will stay here.”

And it was then that he noticed that there was a door in the wall of wheat.

Peter stood and went to the wooden door and knocked on it, and the door swung open.

“Hello?” called Peter.

No one answered him.

“Hello?” he called again.

And when there was still no answer, he pushed the door open further and stepped over the threshold and entered the home he had once shared with his mother and father.

Someone was crying.

He went into the bedroom, and there on the bed, wrapped in a blanket, alone and wailing, was a baby.

“Whose baby is this?” Peter said. “Please, whose baby is this?”

The baby continued to cry, and the sound of it was heartbreaking to him, so he bent and picked her up.

“Oh,” he said. “Shh. There, there.”

He held the baby and rocked her back and forth. After a time, she stopped crying and fell asleep. Peter could not get over how small she was, how easy it was to hold her, how comfortably she fitted in his arms.

The door to the apartment stood open, and he could hear the music of the wind moving through the grain. He looked out of the window and saw the evening sun hanging golden over the field.

For as far as his eye could see, there was nothing but light.

And he knew, suddenly and absolutely, that the baby he held in his arms was his sister, Adele.

When he woke from this dream, Peter sat up straight and looked around the dark room and said, “But that is how it was. She

did

cry. I remember. I held her. And she cried. So she could not, after all, have been born dead and without ever drawing breath, as Vilna Lutz has said time and time again. She cried. You must live to cry.”

He lay back down and imagined the weight of his sister in his arms.

Yes, he thought. She cried. I held her. I told my mother that I would watch out for her always. That is how it happened. I know it to be true.

He closed his eyes, and again he saw the door from his dream and felt what it was like to be inside that apartment and to hold his sister and look out at the field of light.

The dream was too beautiful to doubt.

The fortuneteller had not lied.

And if she had not lied about his sister, then perhaps she had told the truth about the elephant too.

“The elephant,” said Peter.

He spoke the words aloud to the ever-present dark, to the snoring Vilna Lutz, to the whole of the sleeping and indifferent city of Baltese. “The elephant is what matters. She is with the countess. I must find some way to see her. I will ask Leo Matienne. He is an officer of the law, and he will know what to do. Surely there is some way to get inside, to get to the countess and then to the elephant so that it can all be undone, so that it can at last be put right; because Adele does live. She lives.”

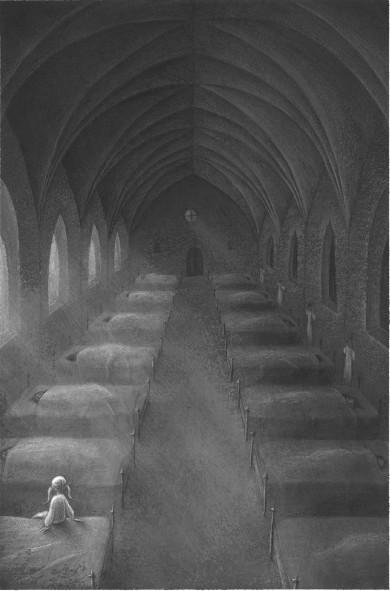

Less than five streets from the Apartments Polonaise stood a grim, dark building that bore the somewhat improbable name of the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, and on the top floor of that building was an austere dormitory with a series of small iron beds lined up side by side, one right after the other like metal soldiers. In each of these beds slept an orphan, and the last of the beds in the draughty, overlarge dormitory was occupied by a small girl named Adele, who, soon after the incident at the opera house, began to dream of the magician’s elephant.

In Adele’s dreams the elephant came and knocked at the door of the orphanage. Sister Marie (the Sister of the Door, the nun who admitted unwanted children to the orphanage and the only person ever allowed to open and close the front door of the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light) was, of course, the one who answered the elephant’s knock.

“Good of the evening to you,” said the elephant, inclining her head towards Sister Marie. “I have come for the collection of the little person that you are calling by the name Adele.”

“Pardon?” said Sister Marie.

“Adele,” said the elephant. “I have come for the collection of her. She is belonging elsewhere besides.”

“You must speak up,” said Sister Marie. “I am old, and I do not hear well.”

“It is the one you are calling Adele,” said the elephant in a slightly louder voice. “I am coming for to keep her and for taking her to where she is, after all, belonged.”

“I am truly sorry,” said Sister Marie, and her face did look sad. “I cannot understand a word you are saying. Perhaps it is because you are an elephant? Could that be it? Could that be the cause of the hindrance in our communications? Understand, I have nothing against elephants. You yourself are an exceptionally elegant elephant and obviously well mannered; there is no doubt. But the fact remains that I can make no sense of your words, and so I must bid you goodnight.”

And with this, Sister Marie closed the door.

From a window in the dormitory, Adele watched the elephant walk away.

“Madam Elephant!” she shouted, banging on the window. “Here I am. Here! I am Adele. I am the one you are looking for.”

But the elephant continued to walk away from her. She went down the street and became smaller and then smaller still, until, in the peculiar and frustrating sleight of hand that often occurs in dreams, the elephant was transformed into a mouse that then scurried into the gutter and disappeared entirely from Adele’s view. And then it began to snow.

The cobblestones of the streets and the tiles of the roofs became coated in white. It snowed and snowed until everything disappeared. The world itself soon seemed to cease to exist, erased, bit by bit, by the white of the falling snow.

In the end, there was nothing and no one in the world except for Adele, who stood alone at the window of her dream, waiting.

T

he city of Baltese felt as if it were under siege – not by a foreign army, but by the weather.

No one could recall a winter so thoroughly, uniformly grey.

Where was the sun?

Would it never shine again?

And if the sun was not going to shine, then could it not at least snow?

Something, anything!

And truly, in the grip of a winter so foul and dark, was it fair to keep a creature as strange and lovely and promising as the elephant locked away from the great majority of the city’s people?

It was not fair.

It was not fair at all.

More than a few of the ordinary citizens of Baltese took it upon themselves to knock at the elephant door. When no one answered the knock, they went as far as to try to open the door themselves, but it was locked tight, bolted firm.

“You stay out there,” the door seemed to say. “And what is inside here will stay inside here.”

And this, in a world so cold and grey, seemed terribly unfair.

Longing is not always a reciprocal thing; while the citizens of Baltese may have longed for the elephant, she did not at all long for them, and finding herself in the ballroom of the countess was, for her, a terrible turn of events.

The glitter of the chandeliers, the thrum of the orchestra, the loud laughter, the smells of roasted meat and cigar smoke and face powder all provoked in her an agony of disbelief.

She tried to will it away. She closed her eyes and kept them closed for as long as she was able, but it made no difference; for whenever she opened them again, it was all as it had been. Nothing had changed.

The elephant felt a terrible pain in her chest.

It was hard for her to breathe; the world seemed too small.

The Countess Quintet, after considerable and extremely careful consultation with her worried advisers, decided that the people of the city (that is, those people who were not invited to her balls and dinners and soirées) could, for their edification and entertainment (and as a way to appreciate the countess’s finely tuned sense of social justice), view the elephant for free, absolutely for free, on the first Saturday of the month.

The countess had posters and leaflets printed up and distributed throughout the city, and Leo Matienne, walking home from the police station, stopped to read how he, too, thanks to the largesse of the countess, could see the amazing wonder that was her elephant.

“Ah, thank you very much, Countess,” said Leo to the poster. “This is wonderful news, wonderful news indeed.”

A beggar stood in the doorway, a black dog at his side, and as soon as Leo Matienne spoke the words, the beggar took them and turned them into a song.

“This is wonderful news,” sang the beggar, “wonderful news indeed.”

Leo Matienne smiled. “Yes,” he said, “wonderful news. I know a young boy who wants quite desperately to see the elephant. He has asked me to assist him, and I have been trying to imagine a way that it could all happen – and now here is the answer before me. He will be so glad of it.”

“A boy who wants very much to see the elephant,” sang the beggar, “and he will be glad.” He stretched out his hand as he sang.

Leo Matienne put a coin in the beggar’s hand and bowed before him, and then continued on his walk home, moving more quickly now, whistling the song the beggar had sung and thinking, What if the Countess Quintet becomes weary of the novelty of owning an elephant?

What then?

What if the elephant remembers that she is a creature of the wild and acts accordingly?

What then?

When Leo came at last to the Apartments Polonaise, he heard the creak of the attic window being opened. He looked up and saw Peter’s hopeful face staring down at him.

“Please,” said Peter, “Leo Matienne, have you figured out a way for the countess to receive me?”

“Peter!” he said. “Little cuckoo bird of the attic world. You are just the person I want to see. But wait; where is your hat?”

“My hat?” said Peter.

“Yes, I have brought you some excellent news, and it seems to me that you would want to have your hat upon your head in order to hear it properly.”