Crucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High (22 page)

Read Crucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High Online

Authors: Kerry Patterson,Joseph Grenny,Ron McMillan,Al Switzler

The answer is a resounding “It depends.” If you want to let a sleeping dog lie (or, in this case, a potential train wreck go unattended), then say nothing. It's the other person who seems to have something to say but refuses to open up. It's the other person who's blown a cork. Run for cover. You can't take responsibility for someone else's thoughts and feelings. Right?

Then again, you'll never work through your differences until all parties freely add to the pool of meaning. That requires the people who are blowing up or clamming up to participate as well. And while it's true that you can't force others to dialogue, you can take steps to make it safer for them to do so. After all, that's why they've sought the security of silence or violence in the first place. They're afraid that dialogue will make them vulnerable. Somehow they believe that if they engage in real conversation with you, bad things will happen to them. Your daughter, for instance, believes that if she talks with you, she'll be lectured, grounded, and cut off from the only guy who seems to care about her. Restoring safety is your greatest hope to get your relationship back on track.

In

Chapter 5

, we recommended that whenever you notice safety is at risk, you should step out of the conversation and restore it. When you have offended others through a thoughtless act, apologize. Or if someone has misunderstood your intent, use Contrasting. Explain what you do and don't intend. Finally, if you're simply at odds, find a Mutual Purpose.

Now we add one more skill:

Explore Others' Paths

. Since we've added a model of what's going on inside another person's head (the Path to Action), we now have a whole new tool for helping others feel safe. If we can find a way to let others know that it's okay to share their Path to Actionâtheir facts and, yes,

even their nasty stories and ugly feelingsâthen they'll be more likely to open up.

But what does it take?

Be sincere

. To get others' facts and stories into the pool of meaning, we have to invite them to share what's on their minds. We'll look at how to do this in a minute. For now, let's highlight the point that when you do invite people to share their views, you must mean it. For example, consider the following incident. A patient is exiting a health care facility. The desk attendant can tell that she is a bit uneasy, maybe even dissatisfied.

“Did everything go all right with the procedure?” the clerk asks.

“Mostly,” the patient replies. (If ever there was a hint that something was wrong, the term “mostly” has to be it.)

“Good,” the clerk abruptly responds and then follows with a resounding, “Next!”

This is a classic case of pretending to be interested. It falls under the “How are you today?” category of inquiries. Meaning: “Please don't say anything of substance. I'm really just making small talk.” When you ask people to open up, be prepared to listen.

Be curious

. When you do want to hear from others (and you should because it adds to the pool of meaning), the best way to get at the truth is by making it safe for them to express the stories that are moving them to either silence or violence. This means that at the very moment when most people become furious, we need to become curious. Rather than respond in kind, we need to wonder what's behind the ruckus.

But how? How can we possibly act curious when others are either attacking us or heading for cover? People who routinely seek to find out why others are feeling unsafe do so because they have learned that getting at the source of fear and discomfort is the best way to return to dialogue. Either they've seen others do

it or they've stumbled on the formula themselves. Either way, they realize that the cure to silence or violence isn't to respond in kind, but to get at the underlying source. This calls for genuine curiosityâat a time when you're likely to be feeling frustrated or angry.

To help turn your visceral tendency to respond in kind into genuine curiosity, look for opportunities to be curious. Start with a situation where you observe someone becoming emotional and you're still under controlâsuch as a meeting (when you're not personally under attack and are less likely to get hooked). Do your best to get at the person's source of fear or anger. Look for chances to turn on your curiosity rather than kick-start your adrenaline.

To illustrate what can happen as we exercise our curiosity, let's return to our nervous patient.

C

LERK

: Did everything go all right with the procedure?

P

ATIENT

: Mostly.

C

LERK

: It sounds like you had a problem of some kind. Is that right?

P

ATIENT

: I'll say. It hurt quite a bit. And besides, isn't the doctor, like, uh, way too old?

In this case, the patient is reluctant to speak up. Perhaps if she shares her honest opinion, she will insult the doctor, or maybe the loyal staff members will become offended. To deal with the problem, the desk attendant lets the patient know (as much with his tone as with his words) that it's safe to talk, and she opens up.

Stay curious

. When people begin to share their volatile stories and feelings, we now face the risk of pulling out our own Victim, Villain, and Helpless Stories to help us explain why they're saying what they're saying. Unfortunately, since it's rarely fun to hear other people's unflattering stories, we begin to assign negative motives to them for telling the stories. For example:

C

LERK

: Well aren't you the ungrateful one! The kind doctor devotes his whole life to helping people and now that he's a little gray around the edges, you want to send him out to pasture!

To avoid overreacting to others' stories, stay curious. Give your brain a problem to stay focused on. Ask: “Why would a reasonable, rational, and decent person say this?” This question keeps you retracing the other person's Path to Action until you see how it all fits together. And in most cases, you end up seeing that under the circumstances, the individual in question drew a fairly reasonable conclusion.

Be patient

. When others are acting out their feelings and opinions through silence or violence, it's a good bet they're starting to feel the effects of adrenaline. Even if we do our best to safely and effectively respond to the other person's verbal attack, we still have to face up to the fact that it's going to take a little while for him or her to settle down. Say, for example, that a friend dumps out an ugly story and you treat it with respect and continue on with the conversation. Even if the two of you now share a similar view, it may seem like your friend is still pushing too hard. While it's natural to move quickly from one

thought

to the next, strong

emotions

take a while to subside. Once the chemicals that fuel emotions are released, they hang around in the bloodstream for a timeâin some cases, long after thoughts have changed.

So be patient when exploring how others think and feel. Encourage them to share their path and then wait for their emotions to catch up with the safety that you've created.

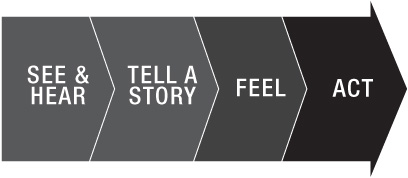

Once you've decided to maintain a curious approach, it's time to help the other person retrace his or her Path to Action. Unfortunately, most of us fail to do so. That's because when others

start playing silence or violence games, we're joining the conversation at the

end

of their Path to Action. They've seen and heard things, told themselves a story or two, generated a feeling (possibly a mix of fear and anger or disappointment), and now they're starting to act out their story. That's where we come in. Now, even though we may be hearing their first words, we're coming in somewhere near the end of their path. On the Path to Action model, we're seeing the action at the end of the pathâas shown in

Figure 8-1

.

Figure 8-1. The Path to Action

Every sentence has a history

. To get a feel for how complicated and unnerving this process is, remember how you felt the last time your favorite mystery show started late because a football game ran long. As the game wraps up, the screen cross-fades from a trio of announcers to a starlet standing over a murder victim. Along the bottom of the screen are the discomforting words, “We now join this program already in progress.”

You shake the remote in exasperation. You've missed the entire setup! For the rest of the program you end up guessing about key facts. What happened before you joined in?

Crucial conversations can be similarly mysterious and frustrating. When others are in either silence or violence, we're actually joining their Path to Action

already in progress

. Consequently, we've already missed the foundation of the story and we're confused. If we're not careful, we can become defensive. After all, not only are we joining late, but we're also joining at a time when the other person is starting to act offensively.

Break the cycle

. And then guess what happens? When we're on the receiving end of someone's retributions, accusations, and cheap shots, rarely do we think: “My, what an interesting story he or she must have told. What do you suppose led to that?” Instead, we match this unhealthy behavior. Our genetically shaped, eons-old defense mechanisms kick in, and we create our own hasty and ugly Path to Action.

People who know better cut this dangerous cycle by stepping out of the interaction and making it safe for the other person to talk about his or her Path to Action. They perform this feat by encouraging him or her to move away from harsh feelings and knee-jerk reactions and toward the root cause. In essence, they retrace the other person's Path to Action together. At their encouragement, the other person moves from his or her emotions, to what he or she concluded, to what he or she observed.

When we help others retrace their path to its origins, not only do we help curb our reaction, but we also return to the place where the feelings can be resolvedâat the source, that is, the facts and the story behind the emotion.

When?

So far we've suggested that when other people appear to have a story to tell and facts to share, it's our job to invite them to do so. Our cues are simple: Others are going to silence or violence. We can see that they're feeling upset, fearful, or angry. We can see that if we don't get at the

source

of their feelings, we'll

end up suffering the

effects

of the feelings. These external reactions are our cues to do whatever it takes to help others retrace their Paths to Action.

How?

We've also suggested that whatever we do to invite the other person to open up and share his or her path, our invitation must be sincere. As hard as it sounds, we must be genuine in the face of hostility, fear, or even abuseâwhich leads us to the next question.

What?

What are we supposed to actually

do?

What does it take to get others to share their pathâstories and facts alike? In a word, it requires

listening

. In order for people to move from acting on their feelings to talking about their conclusions and observations, we must listen in a way that makes it safe for others to share their intimate thoughts. They must believe that when they share their thoughts, they won't offend others or be punished for speaking frankly.

To encourage others to share their paths we'll use four power listening tools that can help make it safe for other people to speak frankly. We call the four skills

power

listening tools because they are best remembered with the acronym AMPPâ

Ask, Mirror, Paraphrase

, and

Prime

. Luckily, the tools work for both silence and violence games.

The easiest and most straightforward way to encourage others to share their Path to Action is simply to invite them to express themselves. For example, often all it takes to break an impasse is to seek to understand others' views. When we show genuine interest, people feel less compelled to use silence or violence. For example: “Do you like my new dress, or are you going to call the modesty police?” Wendy smirks.

“What do you mean?” you ask. “I'd like to hear your concerns.” If you're willing to stop filling the pool with your meaning and step back and invite the other person to talk about his or her view, it can go a long way toward breaking the downward spiral and getting to the source of the problem.

Common invitations include:

“What's going on?”

“I'd really like to hear your opinion on this.”

“Please let me know if you see it differently.”

“Don't worry about hurting my feelings. I really want to hear your thoughts.”